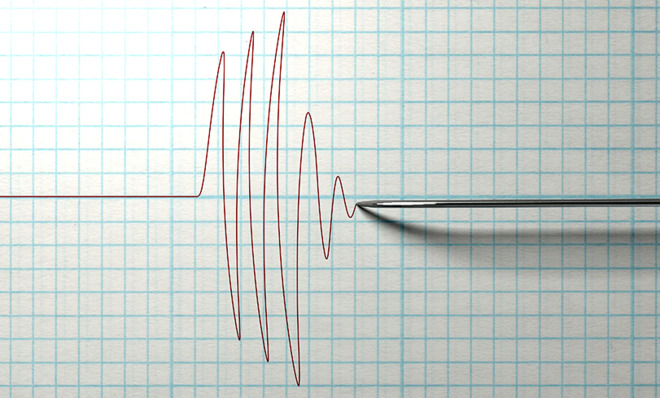

How to beat a polygraph

This may involve visualizing a cool beer on a summer night

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Judging by Doug Williams' business website, it doesn't look like he thought he had anything to hide. On Polygraph.com, Williams, a former officer with the Oklahoma City Police Department turned anti-polygraph activist, promises to teach you how to prepare for (read: beat) a polygraph test — through his how-to manual, DVD, and personal training sessions. He frames his pitch as selling to a very nervous truth-teller, rather than to a liar, writing on his site: "Remember, just telling the truth only works about 50 percent of the time — so to protect yourself from being falsely accused of lying, you must learn how to pass!"

Nevertheless, a grand jury in Oklahoma decided that there is enough evidence that Williams is doing more harm than helping innocent people calm their nerves. In November, Williams was charged with multiple counts of mail fraud and witness tampering, for allegedly showing people how to lie and hide crimes in order to get security-clearance-level jobs with the federal government. Williams calls the charges against him an "attack on his First Amendment rights," and says that he's only being targeted because he is a vocal critic of a method that is "no more accurate than the toss of a coin in determining whether a person is telling the truth or lying."

On the accuracy aspect at least, he's got a point. In United States v. Scheffer, in 1989, the Supreme Court ruled that a judge could reject polygraph results in criminal cases, citing a general lack of scientific consensus as to their reliability. Many state and federal courts now consider them inadmissible as evidence. But it's a decision that's still up to individual judges. And even in places where polygraph tests may not be admissible in court, some branches of law enforcement still believe that they have other, non-prosecutorial value.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For instance, studies have shown that a polygraph can have a kind of placebo effect — that it can elicit new information from people who hadn't been fully cooperating before, who now feel that they have no choice but to come clean. In a majority of jurisdictions, cops and parole officers also use regular polygraph tests to keep post-conviction sex offenders accountable for their actions; researchers have suggested that the process alone discourages recidivism, whether or not the results are 100 percent accurate. (Other researchers disagree.)

But aside from those legal uses, it was the job-screening use of the polygraph that likely sparked federal prosecutors' interest in Williams' case. Last year, McClatchy reported on an unprecedented secret federal investigation of other polygraph instructors like Williams; Chad Dixon was sentenced to eight months in prison after pleading guilty to similar charges. Marisa Taylor and Cleve R. Wootson Jr. wrote, "The criminal inquiry, which hasn't been acknowledged publicly, is aimed at discouraging criminals and spies from infiltrating the U.S. government by using the polygraph-beating techniques."

It's probably worth remembering that news of the investigation came out in September 2013, after the "Summer of Snowden," a series of revelations that set the entire government reeling. A former National Security Agency employee, Russell Tice, told U.S. News & World Report that the agency regularly subjects its agents to polygraph tests, but that he and his colleagues had figured out how to pass every time. (Tips include biting your tongue to spike the sensors' output, and then visualizing cool beers on warm summer nights to reduce them.)

In their article for McClatchy, Taylor and Wootson also described the polygraph-prep instructors' methods, "which are said to include controlled breathing, muscle tensing, tongue biting, and mental arithmetic." The overall goal of the preparation process is to teach people to control the otherwise involuntary physical stress responses that the polygraph's sensors pick up on during the interview. Or, as Williams himself summed up quite simply in a recent tweet: "The polygraph operator monitors your respiration, GSR, & cardio. Get nervous on the wrong question & he calls you a liar!"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many criminologists now believe that "getting nervous" shouldn't indicate a guilty conscience, and that consistent story-telling is a much better indicator of the truth. Psychologists are currently testing new techniques that "induce cognitive load" as potentially more accurate ways to weed out the lies. It takes more brainpower to keep an invented story consistent than it does to tell the truth, the theory goes. So interrogators can try to overwhelm their subjects with information, questions, and tasks, and see how flustered they get.

One review of the research explores methods like having the person draw the scene being described, tell the story in reverse-chronological order, describe the scene in detail from the perspective of a different physical vantage point, and even complete math problems in the middle of the interview. Even being made to maintain constant eye contact occupies the mind, so that can also make it more difficult for a liar to stay on message.

It's hard to say which interrogation method is harder for a liar to beat — manipulating subtle physiological blips, or keeping a complicated story straight while looking the examiner right in the eye and doing long division at the same time. But maybe it's also worth trying the simple, natural, low-tech option that's always been a recourse for liars everywhere: mock surprise. According to Doug Williams' indictment, one undercover agent apparently asked him what to do during the polygraph if he was asked about whether he had had any polygraph training. As in, should he lie about that? Williams apparently responded, "Look at them with an astounded look on your face…reverse it on him."

Pacific Standard grapples with the nation's biggest issues by illuminating why we do what we do. For more on the science of society, sign up for its weekly email update or subscribe to its bimonthly print magazine.

More from Pacific Standard...