Mark Wahlberg should not be pardoned

What kind of message would it send?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In April 1988, Mark Wahlberg, 16, set upon a Vietnamese immigrant named Thanh Lam, and, with a wooden stick, beat him so severely that Lam fell to the ground, unconscious. Later that night, according to contemporaneous accounts, Wahlberg found another Asian man, Hoa Trinh, and, calling him a "gook" and "slant eye," smashed him in the face.

Trinh lost sight in his right eye.

Wahlberg was arrested, convicted, and spent 45 days in jail, an experience that hardened him for the rest of his younger days and provided him creative fodder for many of his later projects. He has insisted that, despite his liberal use of racial slurs, race did not motivate his attack. His intoxication, apparently, did.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Twenty-six years later, Wahlberg wants a formal pardon from the commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Why? He has devoted the rest of his life to being a model citizen. His movies do not glorify violence (apparently). He has contributed significantly to his community. He has mentored many young boys away from a life of crime. He has demonstrated, in deed, a respect for the police.

His pardon application includes the following ambition: "My hope is that, if I receive a pardon, troubled youths will see this as an inspiration and motivation that they too can turn their lives around."

Interesting logic. It works better, though, with this rewrite: "My hope is that, by not seeking a pardon, troubled youths will know that their actions have repercussions, even if they later become wealthy celebrities. Although this wonderful country provides plenty of opportunity for them to turn their lives around, they can never use their renown to erase the indelible consequences of their decisions."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is a young person not going to commit a crime they'd otherwise commit because Wahlberg got his own criminal record expunged? Or would a young person be less likely to commit a crime, (supposing, by the way, that they look to Wahlberg as the arbiter of their ethics) if they knew that even if they managed to overcome obstacles and become successful later in life, they could not get pardoned?

***

Last night, before I heard about Mark Wahlberg's pardon plea, I had dinner with Simon Cho. Cho is a world champion speed skater, who at age 19, sabotaged the skates of a rival on the orders of his coach and was punished by a two-year suspension from the sport. He had been an Olympian, a bronze medalist; he will probably never take to the ice as a competitor again.

His mistake was not criminal, but it will spook him for the rest of his life.

We spoke about the "mess," as he calls it today. Cho took full responsibility for his conduct, accepted the suspension without appeal, and apologized directly to the competitor he curtailed. He was still a kid when he did that, when he faced a battery of cameras and took hostile questions from the press.

He's 23 now. He's slowly rebuilding his life. He is driven, smart, and talented, very self-aware, and will go on to live a great life. He won't forget what he did; he doesn't want to. It reminds him of what he can never do again. When he marries and has kids, he wants to use the lessons he's learned to teach his kids not to make the same mistakes he did.

I'm sure you'll see Cho's story in a few years on one of those ESPN 30 for 30 documentaries. He's passed the point of no return — the end of Act 2, as they say in the movie biz, and he's working quietly to contribute something meaningful.

Both Cho and Wahlberg have lessons to impart about making mistakes and about redemption.

Accepting, fully, your past and its aftermath, is a start. Special dispensation for celebrities is a step back.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ film

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ filmThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

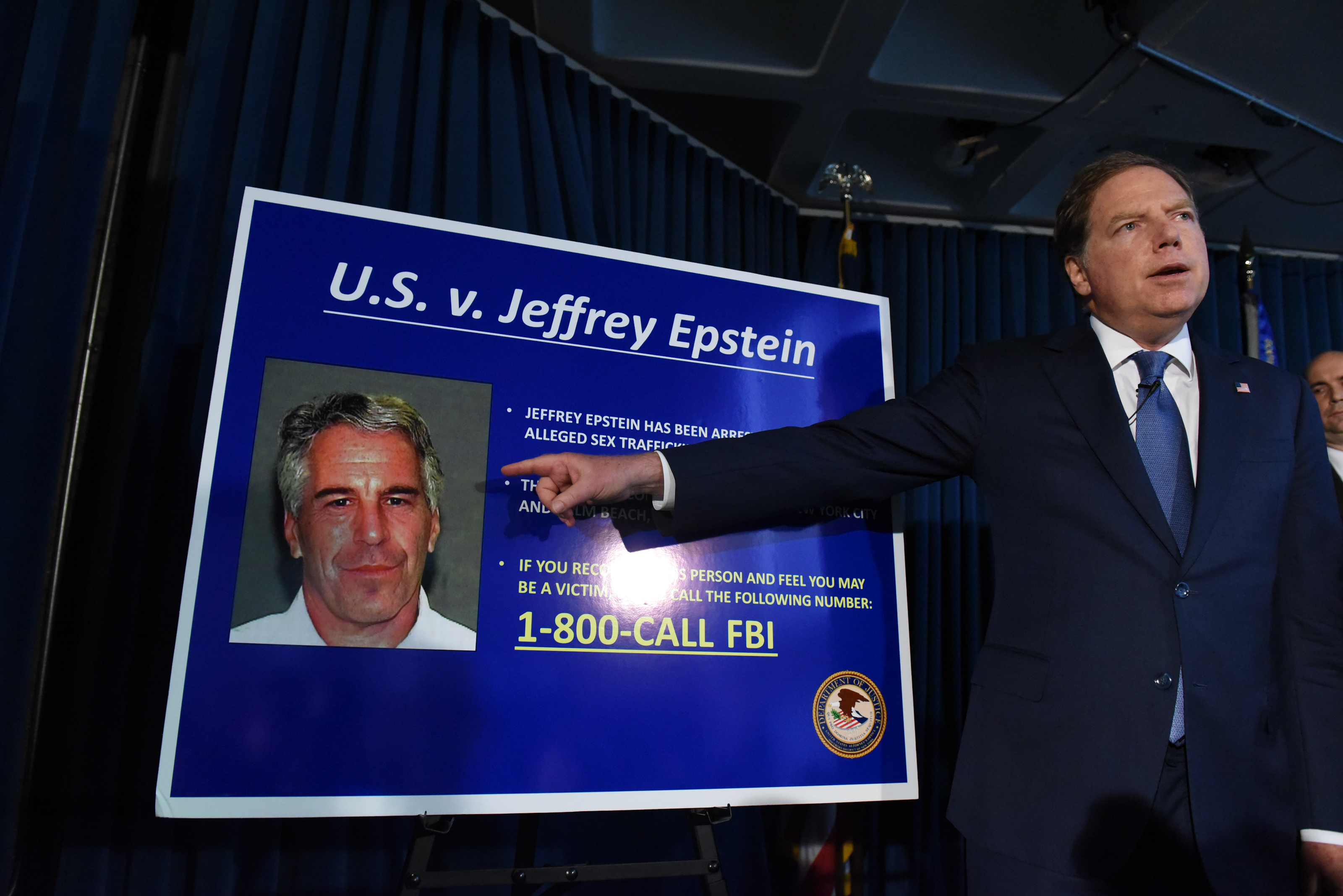

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound