5 great scientists who never won a Nobel Prize

Some Nobel snubs were the product of grudges or biases. Others were matters of bad timing.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Nobel Prizes can be as controversial as they are prestigious. It's very uncommon for a scientist to make a discovery entirely on his or her own: Researchers collaborate, compete, and construct new theories based on the work of others. Inevitably, choosing just up to three living scientists to take credit for a pivotal find means some researchers are, arguably, unfairly left out of the spotlight.

Some Nobel snubs were the product of personal grudges or general biases, particularly against women scientists. Others were matters of bad timing; Rosalind Franklin, whose work was essential to the discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA, died four years before James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins shared a Nobel in 1962 — and the Nobels are almost never awarded posthumously. Here are the stories of a few scientists who contributed significantly to our understanding of the world, but who unfortunately never won top honors in Sweden.

Annie Jump Cannon

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Accomplishment: Classifying the stars

Cannon was an American astronomer hired by Edward Pickering, along with other women (collectively referred to as "Pickering's Harem"), to work at the Harvard Observatory mapping and classifying every star in the sky. Without these women, whom he called "computers," Pickering could not have catalogued all those stars.

(More from World Science Festival: The women who shaped the computer age)

Cannon was arguably the most accomplished of Pickering's computers. During her career she observed and classified over 200,000 stars. But more importantly, she devised a star classification system to categorize stars based on spectral absorption lines. Though her contributions were not recognized during her forty-year astronomy career, her work lives on in the mnemonic device "Oh Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me!" which helps astronomy students remember star types in order of decreasing temperature.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Gilbert Newton Lewis

Accomplishment: Understanding how chemical bonding works

If you've ever studied chemistry, you know the work of Gilbert Newton Lewis, an American chemist. Lewis' contributions to chemistry in the 1900s include discovering the covalent bond (where atoms share electron pairs), and explaining the nature of acids and bases as substances that accept or give away a pair of electrons, respectively. He also introduced the "Lewis dot structure," a way of representing chemical bonds and unbonded electrons in atoms and molecules.

Much of Lewis's research laid the groundwork for our understanding of chemical bonding, and he went on to make significant contributions in thermodynamics as well. But though he was nominated 35 times, Lewis's criticism of his colleagues and hostile relationships with his contemporaries kept him from winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. That's not just idle gossip: There's historical evidence that William Palmaer, a Swedish chemist who served as a voting member of the chemistry committee from 1926 to 1942, had an agenda against Lewis. (Palmaer was close friends with Walther Nernst, a chemist that Lewis nursed a grudge against and frequently criticized).

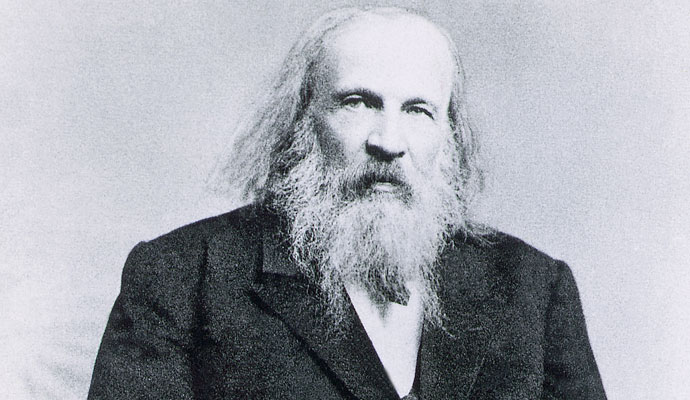

Dimitri Mendeleev

Accomplishment: The periodic table of elements

Mendeleev was a Russian chemist and inventor, well known for his periodic law stating that the chemical properties of the elements reoccur periodically as their atomic masses increase. The famous Periodic Table he created based on this law accurately described elements yet to be discovered along with their physical and chemical properties, and was the first such table that could make these predictions. Mendeleev was nominated for the 1906 Nobel Prize in chemistry, but died in 1907 without that honor.

(More from World Science Festival: The biochemistry of autumn colors)

Carl Richard Woese

Accomplishment: Reshaping the tree of life

Woese was a molecular biologist who studied microbiology and evolution. In 1977, he published a paper that described how to use RNA from the ribosome, a cellular organelle, to identify and classify microbes. This technique, called molecular phylogeny, eventually revolutionized the study of both microbiology and evolution.

Woese's first analysis using molecular phylogeny led to the discovery of the Archaea, a previously-unheard of third domain of life on Earth. Before Woese's discovery, life was classified into Five Kingdoms stemming from two major branches: prokaryotes, containing bacteria, and eukaryotes, comprising animals, plants, fungi and protists. The only difference between these branches was the presence (eukaryotes) or absence (prokaryotes) of a membrane-bound cell nucleus. Microorganisms in Archaea do not have a nucleus, but have their own characteristic membranes, enzymes, and ribosomes. Most Archaea are extremophiles, residing in environments that most organisms would find intolerable: hot springs, volcanic vents, or extremely salty places. Yet despite the fact that Woese literally reshaped the tree of life, he never received a Nobel for his pivotal work.

Chien-Shiung Wu

Accomplishment: Proving the "handedness" of nature

In 1956 Wu conducted a nuclear physics experiment that disproved a widely accepted law of physics: the "Parity Law," which says that physical systems or objects that are mirror images of each other should behave in an identical way — essentially, that fundamental laws of physics do not distinguish between left and right.

While the law of parity does apply to the forces of electromagnetism, gravity, and the strong nuclear force, two other physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen Ning Yang thought that this would not be true for the weak nuclear force. To prove this, Wu — enlisted by Lee, a colleague at Columbia University, where she was an associate professor at the time — studied the decay of supercooled atoms of the radioactive isotope cobalt-60 exposed to a strong magnetic field. If the law of parity held true for the weak nuclear force that governs beta decay, the cobalt isotopes should have emitted equal numbers of electrons in both directions. But Wu saw that as the cobalt-60 decayed, electrons tended to fly off in a direction opposite from the spin of the cobalt nuclei; the law did not hold.

(More from World Science Festival: There'd be no Steve Jobs without Grace Hopper)

Wu's work was later replicated, and became proof positive of parity violation. The 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Lee and Yang for disproving parity violation, but Wu was overlooked. Still, she is often remembered as "The First Lady of Physics."