Should you hope to die at 75? Absolutely not.

In an essay at The Atlantic, Ezekiel Emanuel takes the morally obtuse position that he would prefer not to deal with the indignities of old age

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

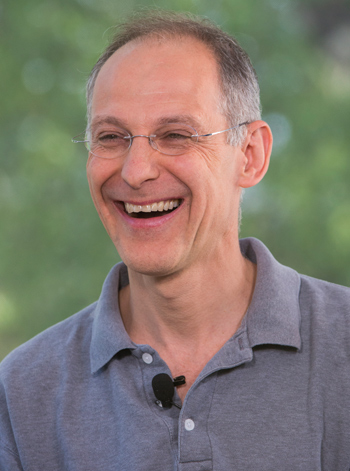

Ezekiel J. Emanuel, 57, wants to die 18 years from now. We know this because he's told us — in the title of an essay that's received an enormous amount of attention since it appeared on the website of The Atlantic last Wednesday.

"Why I Hope to Die at 75" is one of those essays that will spark a nationwide conversation and debate. But that doesn't mean it's smart. On the contrary, given the author's prominence in the world of health-care policy — he played a major role in designing ObamaCare, contributes frequent health-care-related op-eds to The New York Times, directs the Clinical Bioethics Department at the National Institutes of Health, and heads the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania — what's most noteworthy about the essay is its stunning combination of wisdom and insight with moral idiocy.

First, the good news.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In certain passages of the essay, Emanuel writes intelligently and critically about a cultural aspiration that he calls, with irony, "the American immortal." This futile desire "to cheat death and prolong life as long as possible" leads Americans to be "obsessed with exercising, doing mental puzzles, consuming various juice and protein concoctions, sticking to strict diets, and popping vitamins and supplements." And of course, it also motivates the quest to devise treatments for life-threatening maladies — heart attack, stroke, cancer — well into people's eighth and even ninth decades of life. Such treatments not only cost enormous sums of money; in many cases, they also lead to deaths that are far more drawn-out, debilitating, and painful than they otherwise would be.

Emanuel is right to raise the question of whether people who opt for heroic medicine late in life are really furthering their quality of life or merely adding marginally to its quantity. And his concrete discussion near the end of his essay about which treatments and routine tests, screenings, and interventions he plans to forego when he reaches 75 deserves to be pondered by everyone as they approach old age.

If this were the sum total of Emanuel's argument, his essay could have been titled "Why I'll Accept Death at 75." It would have counseled against attempting to stave off the inevitable, and urged older men and women to resign themselves to mortality. That would have been a useful contribution.

But that's not the sum total of Emanuel's argument. Far from saying that he'd be willing to accept death at 75, he goes much further — to say that he positively hopes to die at 75. And that's where his essay goes off the rails.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Emanuel's case for dying at 75 rests on his view of the personal qualities that make life worth living — and their radical incompatibility with advanced aging. All of those qualities are wrapped up with how we are perceived by others, and especially by our families. When we contemplate how our children will remember us, Emanuel claims, we hope they will think of us "in our prime," which he defines in the following terms: "Active, vigorous, engaged, animated, enthusiastic, funny, warm, loving…independent." These attributes contrast sharply with the debilities of old age. We most certainly don't want to be remembered as "stooped and sluggish, forgetful and repetitive, constantly asking, 'What did she say?'"

As far as Emanuel is concerned, "frailty is the ultimate tragedy."

If there's a single word that encapsulates Emanuel's view of what can make life after 75 worse than death, it is "disability." We will all end up disabled if we live long enough, either through decline into senility and Alzheimer's or simply through the slow physical degeneration of aging. Yes, heroic medicine can save those who suffer cancer, heart disease, and stroke, even at advanced ages. But these survivors are usually left fragile and decrepit. Instead of being "vibrant and engaged," they become "feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic." And that is something that Emanuel would rather die than endure, and he wants to persuade his readers to feel the same way about themselves.

Reading Emanuel's essay, I began to despair — not just about the moral outlook it expresses, but about whether its readers will even recognize how monstrous it is. Emanuel has taken the ethic of meritocratic striving that currently dominates elite culture in the United States and transformed it into a comprehensive vision of the human good. Viewed in its light, the only life worth living is one in which you endlessly, relentlessly strive to look as smart and clever as possible in the eyes of other smart and clever people. The ultimate goal of such a life is to be considered the smartest and cleverest person of all. Once old age or any other misfortune gets in the way of continually striving for that goal, one might as well cease to exist.

But what about everyone else? This includes the millions upon millions of Americans who don't help to write major pieces of legislation, don't pen op-eds for leading newspapers, don't run departments at the NIH, and don't head institutes at Ivy League universities. Any one of those credentials would be impressive. But all four? Zeke Emanuel's accomplishments — like those of his brothers, Chicago Mayor and former White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel and Hollywood talent agent Ari Emanuel — are extraordinary.

The Emanuel brothers have clawed their way to the very top of the American elite. How could the rest of the country hope to measure up to them? Doesn't a middle manager toiling away in an anonymous office on the outskirts of Des Moines — let alone a burger flipper earning the minimum wage at a McDonald's down the road — possess far less intelligence, talent, and ambition? Isn't he comparatively disabled? And if so, shouldn't he hope to die right now rather than waiting for 75?

This isn't just an academic question. Emanuel and his striving siblings have an adopted sister named Shoshana who suffers from cerebral palsy. The clear implication of Emanuel's argument is that her life — like that of someone who endures a steep decline in old age — is not worth living. Is that what Emanuel really thinks? If so, he should say so explicitly. If not, he should explain why not, since every word of his essay appears to push in the opposite direction.

Though he would no doubt blanch at the suggestion, Ezekiel Emanuel has written an essay that in its implications clearly amounts to a defense of eugenics. Yet Emanuel's position differs in one important respect from the version of eugenics that rose to prominence in the Western world in the early decades of the 20th century. Whereas eugenics was originally motivated by public-spirited ends — by the desire to purify the race for the sake of overall human flourishing — Emanuel's version is provoked by a more personal concern: Extraordinarily creative, intelligent, ambitious, and successful individuals want to be seen and remembered as exemplars of "vitality," and not as "burdens" slowly succumbing to the "agonies of decline."

This is eugenics induced by narcissism.

To which the proper response is a firm insistence that every person possesses an intrinsic dignity and worth just by virtue of being human. This will even be true of Zeke Emanuel decades from now, when age and debility will have conspired, inevitably, to deprive him of some of his overabundant stupendousness.

No one should hope to die — at 75, 80, 90, or ever.

(Photo credit: Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis)

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.