Is 'feminism' just another word for 'liberalism'?

There isn't much room for conservative women in the modern feminist agenda

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

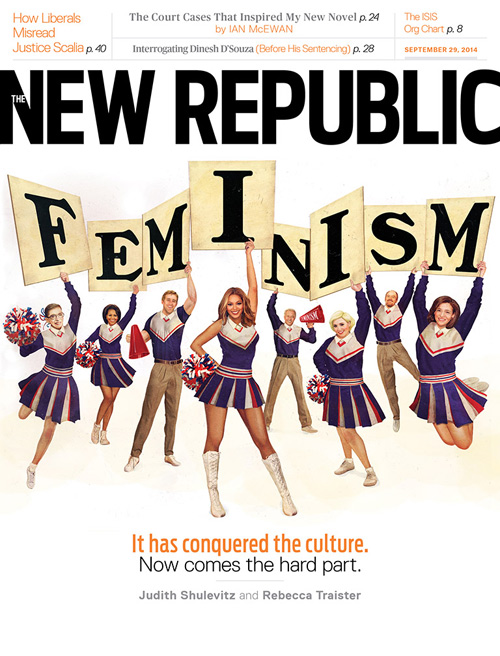

It's an amusing cover. Under the standard The New Republic logo on a white background, we have Beyoncé, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Michelle Obama, Louis CK, and a handful of other smiling pop-culture and political Icons of the Moment dressed as cheerleaders, lifting letters high into the air: "F-E-M-I-N-I-S-M." And beneath the image, the subtitle of the cover story: "It has conquered the culture. Now comes the hard part."

Inside the magazine, the hard part is hashed out by Judith Shulevitz and Rebecca Traister, two TNR senior editors. They haven't so much written an essay together as penned a series of missives in which they mull over and debate feminism's past, present, and possible future.

The exchange is well worth reading. But it also raises and leaves unanswered important questions about what feminism has become in the opening decades of the 21st century. Is it a movement for civic equality that, in theory at least, should appeal to all American women (and ideally, men), regardless of their political commitments or cultural outlook? Or is it merely the women's caucus of the Democratic Party?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

First-wave feminism (during the 19th and early 20th centuries) agitated for the right to vote and other fundamental civic freedoms for women. The second wave (beginning in the early 1960s) focused primarily on social and cultural obstacles to women working outside the home, earning equal pay, and gaining reproductive rights. Its watchword was "choice": women should be just as free as men to pursue careers, to decide whether and when to have children, and so forth.

Whether that second wave is still breaking or has been succeeded by a third or even fourth one, the feminist agenda hasn't changed much since the days of Betty Friedan. Sexual violence remains a significant problem in the U.S. and around the world. Women continue to be paid less than men for the same work. America's lack of paid family leave and universal day care puts enormous strain on women and families. The Hyde Amendment prevents the federal government from funding abortion for poor women.

Those are some of the issues that Shulevitz and Traister highlight in their conversation. Despite some differences in emphasis and temperament, they largely agree that any feminist agenda going forward must build on and respond to these problems.

But what if a woman chooses to use her civic freedom to fight against legalized abortion — organizing in support of the Hyde Amendment, pushing her state legislature to burden abortion clinics with so many regulations that they close down, thereby depriving women of the means to safely exercise the full range of their reproductive rights?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is this politically savvy anti-abortion woman an anti-feminist? Or a feminist role model?

If abortion is too much of a hot-button issue, how about paid family leave, which would guarantee a paycheck to people who take limited time off from work to care for newborns and others family members in need? Both Shulevitz and Traister strongly support it — as have I, for many years. But what are we to make of a libertarian woman who writes influential essays against paid family leave because she believes it will produce far more harm than good for working men and women by driving companies out of business and leading to a net loss in jobs?

Is this woman an enemy of feminism? Or an exemplar of feminism in action?

You get the idea. If feminism is about empowering women to participate in American civic and social life without regard to the ends they pursue with that power and freedom, then of course these women are feminists. The opposite of being a feminist in this sense isn't to be an anti-abortion libertarian; it is to be powerless.

But many self-described feminists today define feminism in a way that is far more ideological and includes a range of specific policy proposals. To be a feminist in this sense, you must support abortion rights through all three trimesters, favor paid family leave, back government subsidized child care, and so forth.

Which means that to be considered a feminist, you must be a liberal Democrat.

TNR is a liberal magazine, so it's no criticism to point out that Shulevitz and Traister both write as liberals. Still, I found myself most intrigued by passages in their exchange where tensions between these rival notions of feminism lurked just below the surface. In her list of feminist priorities, for example, Traister includes "elect a feminist woman president." Had she simply written "elect a woman president," this would have been a statement in keeping with the first form of feminism, which seeks to empower women without regard to ideology. It would have indicated that a victory for any woman of either party in the race for the presidency would be a triumph for feminism.

But that's not what Traister wrote. She wants to elect a feminist woman president, which means that she wants to elect not any woman, but only a liberal woman. She goes out of her way to clarify that this does not mean she thinks feminists need to support Hillary Clinton in 2016. But Elizabeth Warren (who is more liberal than Clinton on most issues) is the only other potential candidate she mentions — implying that the feminist options range from the center to the left wing of the Democratic Party.

Is it even conceivable that Traister, Shulevitz, and other committed feminists would put aside their liberalism to support a conservative woman in a run for the White House against a liberal man? I don't think so. And in such a situation, would these feminists suffer any serious pangs of guilt for having put their liberalism ahead of their feminism? Of course not — because for many feminists today, no conflict between those commitments is possible.

Feminism may well have conquered the culture. But liberalism has also conquered feminism.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’The Week Recommends Put an end to endless swiping and make real romantic connections

-

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moon

Elon Musk’s pivot from Mars to the moonIn the Spotlight SpaceX shifts focus with IPO approaching

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred