Even critics of the euro didn't see this coming

Recent studies show that the trade boost between eurozone countries didn't turn out as expected

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Even long-term critics of the euro — the European Union's single currency shared by 18 European countries — expected that a single currency would boost trade among participants by reducing conversion costs and exchange rate fluctuations. This was one of the chief justifications of the project.

As Allister Heath of The Telegraph points out, critics of the project (such as myself) have focused on other problems, e.g., the dangers of a one-size-fits-all approach to interest rates and monetary policy, as well as the loss of countries' ability to devalue their currencies to stimulate their economies and reduce unemployment. The ongoing euro crisis — which has resulted in an economic depression in the eurozone since 2008 and huge levels of unemployment — illustrates that those arguments were very realistic.

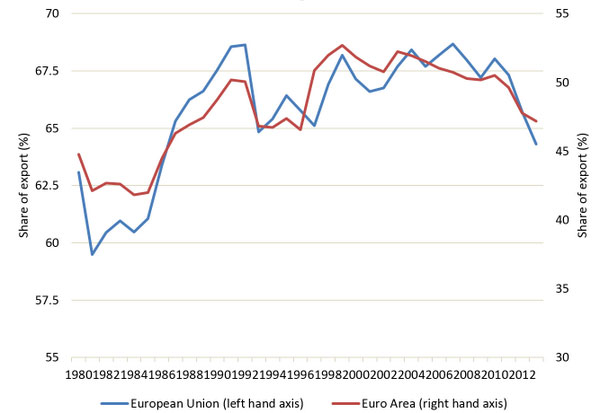

But recent evidence — such as this study by Bruegel's Giulio Mazzolini — shows that the trade boost expected by supporters of the euro is dubious at best. The proportion of European exports to other countries in both the European Union and the eurozone after rising sharply during the 1980s before the introduction of the single currency has actually fallen since the introduction of the euro on the 1st of January 1999:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Heath points out: "This wasn’t caused by the financial crisis, though of course the hit to cross-border trade finance won't have helped."

Instead, Europe has started exporting a greater proportion of goods and services to nations outside the European Union. According to the European Central Bank, eurozone exports have increased to rising economic powers China, Russia, Turkey, India and Brazil in the last decade, and even to Switzerland, which is in Europe but not a member of the European Union or the eurozone. Exports to the United States declined.

So has the single currency completely failed? Not necessarily. The removal of trade and exchange barriers was still beneficial in itself — which is probably one of the reasons why the eurozone experienced fast economic growth between the introduction of the euro and the onset of the 2008 financial crisis — even if those benefits have since been outweighed by the onset of the economic depression in 2008 and subsequent mass unemployment. That's why European governments and the European Central Bank need to pull their finger out and engage in large-scale economic stimulus to fix the mess that has grown and grown in the years since 2008.

But the underlying story is the shift in global economic gravity from Europe and the United States to the emerging markets in Asia and South America. As Heath colorfully points out:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As the emerging markets continue to outgrow the sclerotic, decadent, and decaying continent, more and more of the exports of Europe's most successful companies will go to China, Brazil, or India. As the Pew Research Centre has noted, United Nations statistics show that half of the world's population of 7.2 billion people now live in just six countries. China is largest (1.4 billion), followed by India (1.3 billion), the US, Indonesia, Brazil, and Pakistan, totalling 3.6 billion people. Forget about the eurozone and its ineffective currency: that is where the markets will be. [The Telegraph]

The trade barriers that the euro was supposed to eliminate have gone. But the incentives to trade across those former trade barriers have diminished as new economic powers — offering a wide array of goods and services — have risen. In that light, the eurozone looks very much like a solution to a 20th century problem.

John Aziz is the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate editor at Pieria.co.uk. Previously his work has appeared on Business Insider, Zero Hedge, and Noahpinion.