Why Good Friday is so important to Christians

If the crucifixion story tells us an unbelievable story about God, it tells us a very, very believable story about man: that we are violent and cruel

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

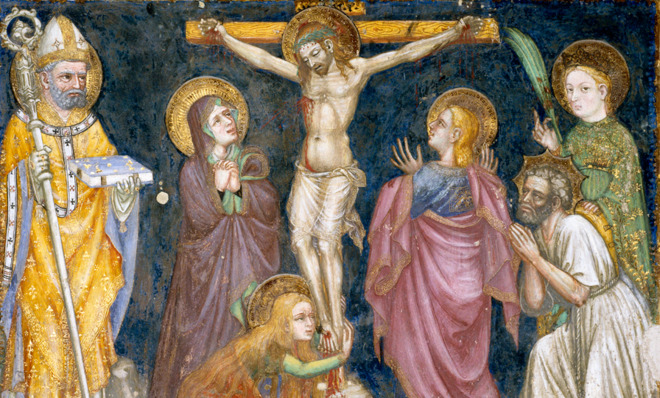

As I explained on Holy Thursday yesterday, for most Christians, this is the most important week of the year. We are commemorating the crucifixion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Jesus had his last meal with his disciples on the evening of a Thursday (commemorated as Holy Thursday), was arrested during the night, tried Friday morning (Good Friday), condemned, crucified, and died before sundown on Friday. And, according to the Gospel accounts, he was bodily raised from the dead on the third day — Sunday, the day of Easter.

That Jesus of Nazareth was executed on a cross is pretty much the one thing that everybody who has heard of him knows about his life. It's the one part of his life that almost all historians agree on, too. And that is what we're commemorating today, Good Friday.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, to Christians, this historical event has special meaning. And not just for the self-evident reason that it ended the life of the one whom we consider to be the most important person in all of history.

We Christians believe that Jesus of Nazareth wasn't just a preacher with nice things to say, but the only Son of God. And not just the Son of God, but God Himself. Christians believe that God is not some really powerful dude in the clouds, but the impossibly transcendent source of all being. Christians believe that God is so transcendent that he cannot even be said to "exist" in the common sense, the way you and I exist — rather, God is the very nature of being itself, and sustains all existence.

Christians believe that this impossibly transcendent God — there are no two ways to say this — died. Was killed. By some no-name Roman soldier.

Yeah, it makes absolutely no sense.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But we Christians believe this. So how do we explain the inherent contradictions?

The Christian pastor Tim Keller has a nice, if somewhat reductive, way of putting it: Every other world religion was founded by a man who said, "Follow me, and you can find God"; Christianity is the only religion that was founded by a man who said, "I'm God, come to find you." And because Christians believe that the very nature of God is to love, according to God's bizarre, otherworldly logic, the way to "come find" us was to embrace what is most bitter about human experience: suffering, agony, loss.

The abandonment is complete. The same Christian texts that proclaim that Jesus is God also record him as exclaiming, before dying: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" The paradox is complete: Even God experienced total separation from God.

The cross became a Christian symbol in part because of bravado. The worst punishment of the Roman Empire was the cross, and the Christians held it up to their tormenters, essentially saying: "We're not afraid of you."

But mostly, the cross is the symbol for Christians because it represents this unique conception of God: a God who is not just the prime mover of everything, but a God who loves his creatures so much that he is willing to do anything to save them.

And the cross is important for Christians not just because of what it says about God, but what it says about humanity. A priest once pithily summed up the meaning of the Christian Gospel: "If you don't love, you're dead; if you love, they'll kill you."

Jesus wouldn't have had to die if his contemporaries had been willing to listen to his message. But we never do. History all-too-readily testifies that our urge to destroy is universal.

Several scholars have pointed out that the story of the crucifixion has some aspects in common with myths of other religions: the scapegoat, who is ritually executed and then divinized. The scholar René Girard believes that these scapegoat myths reveal the true nature of society. Every society looks for scapegoats, for people to blame for breaking the social order, for people to blame for everything that goes wrong, for people to blame to rid us of the nagging feeling that the problem might be us. From silly online ragefests to genocide, we are always on the hunt for scapegoats.

But Girard goes on to note that the Jesus story is an inversion of these other myths. In the ancient scapegoat myths, the scapegoat is guilty. In the Greek tragedy, Oedipus really did sleep with his mother and kill his father; Remus really did step over the boundaries of Rome. But the Gospel narratives loudly assert Jesus' innocence.

In other words, the crucifixion lays bare the reality about the human experience and human suffering: that all societies are founded on violence and that, most of the time anyway, we turn our violence on the innocent.

If the crucifixion story tells us an unbelievable story about God, it tells us a very, very believable story about man: that we are violent and cruel.

The crucifixion shows us the humility of God, and also teaches us some humility. It shows us that, precisely because he became lower than us, God is better than us.

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.