How dangerous is Fukushima's radioactive water?

Because it's headed our way

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It is clear that radioactive water from Fukushima has been dumped into the Pacific Ocean. The contaminated water's arrival to U.S. shores is imminent, but, as of now, there's apparently little cause for concern.

The radioactive water expected to reach U.S. shores early this year has been deemed safe by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Committee — the amount of radiation to reach the West Coast is at a level 100 times less than the drinking water standard.

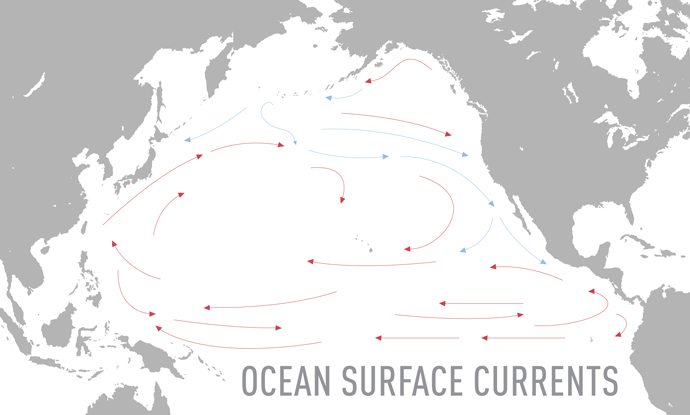

The long journey these radioactive particles are taking through the Pacific is shedding new light on how ocean currents circulate around the world, and helps explain how the radiation diluted so quickly.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As for sea life, it is expected that local fish and plant life in Japanese waters have absorbed the brunt of the radiation, and could pose a threat if consumed, but for those fish that are out farther, the potential for contamination should dissipate. There are caveats, of course. For one, strontium is a bone-seeking isotope, and it may be more persistent than other radioactive elements.

Pacific Ocean currents circulate water between coasts. Estimates suggest contaminated water takes around three to five years to reach the U.S. from Japan.

As far as we know, there is no safe level of exposure to radiation. Regulatory limits are arbitrary — merely a measure of the risk governing bodies are willing to accept. At low-level exposure, the main concern is developing cancer, and less exposure equates to reduced risk of developing cancer. But since the cancer doesn't show up immediately, and the global incidence of potentially deadly radiation exposure is thankfully small, data points are limited. Most of our understanding of radiation exposure in large populations comes from studies of survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, and these studies are imprecise at best. Those who lived miles away, in the countryside, received a lower dose of radiation, and their instances of cancer have been tracked, but it's already been demonstrated that country-dwellers have different cancer rates than city-dwellers, reducing the predictive value of such data.

There are a number of factors that can lead to cancer, of course, and radiation is a fairly weak carcinogen. A person living in the U.S. who hasn't been exposed to radiation has roughly a 40 percent chance of developing cancer in their lifetime (44 percent for men, 38 percent for women). "So radiation is going to increase that by a pretty small amount, a low dose of radiation, shall we say [to] 40.01 percent," says Dr. Brenner. Cigarette smoking, for example, has a much higher impact on incidences of cancer, and small changes in smoking behaviors easily dominate any effect of radiation. Interestingly, this affects the Hiroshima and Nagasaki studies, because cigarettes were easier to obtain during WWII than after.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Because the effects of low-level exposure are not readily evident, and difficult to predict from incomplete data, it will take scientists a long time to determine the full impact of this event.

More from World Science Festival...