Liberalism's quiet revolution

Our domestic politics are maddeningly divisive. But around the world, liberalism is winning.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let's face it: Day-to-day politics can be boring.

Take the State of the Union. It was a perfectly lovely speech, but the most-talked about policy proposal the day after was something called MyRA, a small-bore proposal for reforming retirement accounts. Not exactly the Great Society.

When we zoom in too much on these sorts of moments, we miss the bigger tectonic changes that are transforming our political world for the better. Take a step back, and you'll notice we live in a profoundly exciting, even revolutionary political age. And it's a liberal revolution.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Many people aren't used to thinking of liberalism as a force for radical change. But it always has been, and it explains one of the great features about our liberal world: its push towards equality.

Now, when I say "liberalism," I don't mean it in the conventional sense of "whatever it is that the American center-left believes at the moment." Rather, I mean liberalism in the original sense, the political package of limited democratic government and individual rights.

Liberalism dominates the political landscape today, especially in the Western Hemisphere, so we're used to taking it for granted. Liberal revolutionaries of the past would likely envy us; the American and French Revolutions were famously radical challenges to monarchy, the 800-pound ideological gorilla of the day.

Klemens von Metternich, the 19th century OG Henry Kissinger who committed the Austrian monarchy to an aggressive anti-liberal containment policy, didn't mince words about the liberal menace. "Union between the monarchs is the basis of the policy which must now be followed to save society from total ruin," he wrote. "Speak of a social contract, and the revolution is accomplished!"

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That last line was intended primarily as a jab by Metternich at liberal naivete, but it also neatly encapsulated Metternich's accurate fear about the viral spread of liberal principles. The Austrian prince believed that liberal ideals of freedom and equality were like seeds: Once they took root, they had a way of growing uncontrollably, upending existing hierarchies in their drive to drink in democracy's sunlight.

Metternich was right. Liberal institutions are grounded in a basic moral ideal of equality, one that pushes liberal societies in a relentlessly egalitarian direction, and perpetually puts conservatives on the defensive.

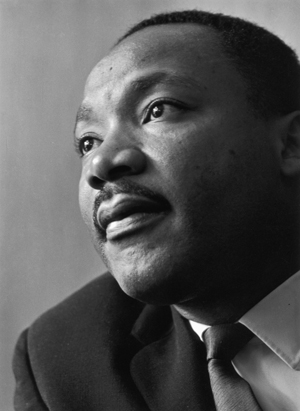

In his "I Have a Dream" speech, Martin Luther King, Jr. famously cast America's founding documents as "promissory notes." This is perhaps the most eloquent encapsulation of the liberal promise. Though races were manifestly unequal at the time of America's founding, the "the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence" were promises that one day, the idea of equal citizens before the law that the revolutionaries fought for would be extended to everyone.

King's "promise" is at once a logical and cultural idea. Logically, if you say "all men are created equal," you can't stop people from asking why it's "all white men," "all rich men," or "all men." If people grow up deeply believing in the ideal of equality, they'll start asking those questions. Hence the great egalitarian social movements (race, gender, sexual orientation, and labor) of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Seeing as how these social revolutions spread globally, the promissory note is not just a peculiarly American idea. It's built in to the structure of liberalism itself. Liberalism's central beef with monarchy was that monarchy rested on the idea that some persons were, by virtue of who their parents were, more equal than others in the eyes of the law. Liberals challenged that, arguing that governments, to be legitimate, needed to take into account the opinions of all its citizens rather than make them comply with the king's dictates at the point of a musket.

Philosopher Charles Larmore calls the moral ideal at play here "the principle of respect for persons," a basic impulse that people, because they're thinking beings, deserve not to be forced to live in a political system they haven't chosen. Larmore's principle is inherently an egalitarian one, as it appeals to the essential human qualities that, of course, we all share.

So if the core principle behind liberal democracy entails the idea that we're all equal, then it make sense that people raised in liberal democracies will be inherently intolerant of inequalities. When your entire social ideal depends on the idea of equality, people raised on that social ideal will chafe at manifest inequality. This is true of all kinds of inequalities, including economic ones. Why else has the maturation of liberal democracy gone hand-in-hand with the rise of the welfare state?

Now, I'm not trying to be the liberal version of a Marxist historian here. "History" doesn't just make liberal societies on its own. Individual people and movements have to figure out how to marshal this inclination towards equality to produce political systems that are actually egalitarian.

Moreover, there are powerful and cross-cutting countervailing pressures to liberalism's egalitarian core. A number of studies have explained America's relatively stingy welfare state, for instance, by referencing the legacy of slavery and racism. But liberalism's long-running track record of egalitarian progress shows that the egalitarian impulse can be more than a match for such forces when properly harnessed.

Understanding liberalism in this light reveals two important truths about American politics. First, there's a reason conservatives often see themselves as fighting hopeless rearguard battles. The past and present are full of inequalities, and conservatives who see something worth saving in them often lament that the egalitarian tide is taking the past's baby along with its bathwater. As long as there are inequalities, the egalitarian impulse will push people to change them. And that means tearing down institutions conservatives might find other kinds of value in.

Second, it explains the increasingly global nature of democratic politics. In a response to my last column, my colleague Damon Linker argued that politics "is always exclusionary — at its most basic level distinguishing between who is and who is not a citizen of a particular political community." Politics, for Linker, must be focused on the good of the community it serves ("the national interest") and not universal moral ideals.

But liberalism is inseparable from its universalistic moral core. There is no plausible reason why, in liberal terms, governments should care about people inside their lands more than others. Borders are just lines on paper, arbitrary historical accidents rather than deep markers of moral communities. Liberalism's egalitarian premises deny that politics is exclusionary altogether; in fact, they push us towards radical inclusion in the name of equal respect for all persons.

We live in a time when liberalism has become increasingly mainstream worldwide. The project of foreign aid, for instance, is historically unprecedented; the idea of governments giving to others out of a sense of moral duty owes a lot to liberal ideas of political obligation beyond our borders. Given liberalism's egalitarian track record, we should be wary of underestimating its power to radically reshape the world into a more global community.

How's that for boring?

(Image courtesy Reg Lancaster/Express/Getty Images)

Zack Beauchamp is a Reporter/Blogger for ThinkProgress. He previously contributed to Andrew Sullivan's The Dish at Newsweek/Daily Beast, and has also written for Foreign Policy and Tablet magazines. Zack holds B.A.s in Philosophy and Political Science from Brown University and an M.Sc in International Relations from the London School of Economics.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred