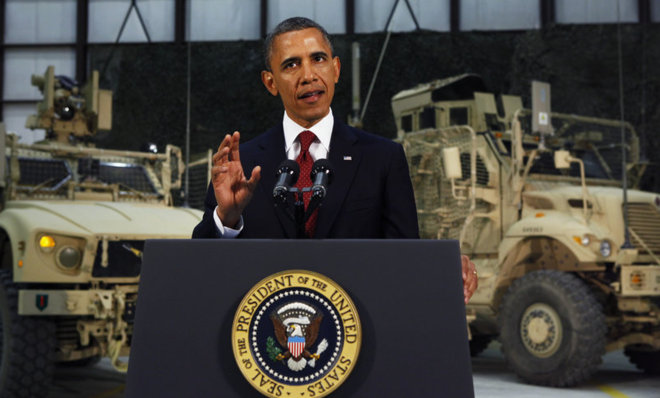

No surprise, Sherlock: Of course Obama wanted to get out of Afghanistan

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“And I must tell you...when it comes to predicting the nature and location of our next military engagements, since Vietnam, our record has been perfect. We have never once gotten it right, from the Mayaguez to Grenada, Panama, Somalia, the Balkans, Haiti, Kuwait, Iraq, and more — we had no idea a year before any of these missions that we would be so engaged."

Prescient remarks from Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, whose soon-to-be published memoir has landed with a predictable bang. There are two strings I want to pull. One: Why did Gates write the book for release during the administration? And two: What do his observations tell us about the man who now holds executive power and the woman, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who aspires to it?

On the first: I'm not surprised Gates allowed his publisher to release the book with two full years left in the Obama administration. It will be more influential now; the gestation time for major Washington memoirs has sped up along with the rest of the city. Does Gates have an obligation to be silent until Obama finishes his term? What degree of loyalty is Obama owed? Not a whole lot. It may not be classy to criticize the president, but unless the publication of a memoir would really harm the president's ability to function, I'm not sure why market forces wouldn't and shouldn't trump custom.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The worst that can be said of Gates is that he either lacks or disregards a sense of old-world propriety. Oh, well. Obama's a big boy. He can handle it. And if Gates intends for his book to matter, to be something more than a bank account padder, publishing it now is a decent decision.

So what of the content? I really need to read the full book to appreciate the context of statements like: "He doesn't believe in his own strategy, and doesn't consider the war to be his. For him, it's all about getting out."

Well, yes, that's exactly the strategy, one that Obama believes in, and has prosecuted quite effectively, if the number of troops in Iraq and Afghanistan are indicators. During his campaign, Obama came to see "winning" in Afghanistan as merely the eradication of al Qaeda from a position of influence. He saw the war there as a self-perpetuating cycle of blood: Troops led to violence, which led to more troops, which weakened America's position.

He did not believe that Afghanistan could be stabilized; he hoped, yes — but the options he had were constrained by decisions made well before he became president. He inherited a war that had no objectively viable endgame. So he chose smaller goals, which were based on his appraisal of what he could do that would increase, relative to the present, American national security interests. Stabilizing Afghanistan, transitioning to an elected government, supporting civil society — these were noble, ancillary, obviously non-resourced objectives. The whole project of getting into these wars and staying, leaving a big American footprint — that's what Obama ran against. He ran to get out of that.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What was up for debate was the mechanism of withdrawal, or how long it would take. Obama's principle priorities were two: The safety of redeploying American troops and ensuring that al Qaeda could not be reconstituted in the region.

Why Gates should be surprised by this is difficult to tell from the excerpts. He is smart enough to have interpreted Obama's campaign rhetoric realistically. He is also, funnily enough, convinced that Obama made the right calls.

Memoirs, and memory, are curious things.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred