The case for abolishing the debt ceiling

An anachronistic holdover from World War I could torpedo the global economy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With Congress possibly headed toward an apparent deal to avert a government shutdown, lawmakers can finally feel optimistic about sidestepping an economic calamity.

Or they could, were it not for the fact that weeks after the federal fiscal year wraps up on September 30, Congress will face yet another deadline, this one to raise the debt ceiling. If Congress does not act in time — the Treasury pegs the deadline at October 17 — the U.S. would risk a catastrophic default on its financial obligations.

House Republicans have already said they plan to demand a host of pet provisions in the next debt ceiling negations, like a one-year delay of ObamaCare. President Obama has flatly said he will not negotiate on the subject, setting up a high-stakes fight.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Which prompts the question: Why bother having a debt ceiling at all?

There is no debt limit in the Constitution. Congress created the cap during World War I to give the government more flexibility to borrow money, so long as it stayed below a set threshold.

Politicians are fond of framing the debt ceiling as a debate about government spending run amok. Yet the ceiling does not deal with future spending, but rather limits the government's borrowing power to fulfill financial commitments that were made in the past.

Therefore, the U.S. "doesn't need, and shouldn't have, a debt ceiling," The New Yorker's James Surowiecki wrote in 2011, because it's an outdated mechanism that merely places a theoretical check on spending.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The only reason we need to lift the debt ceiling, after all, is to pay for spending that Congress has already authorized. If the debt ceiling isn't raised, we'll face an absurd scenario in which Congress will have ordered the president to execute two laws that are flatly at odds with each other. If he obeys the debt ceiling, he cannot spend the money that Congress has told him to spend, which is why most government functions will be shut down. Yet if he spends the money as Congress has authorized him to he'll end up violating the debt ceiling. [The New Yorker]

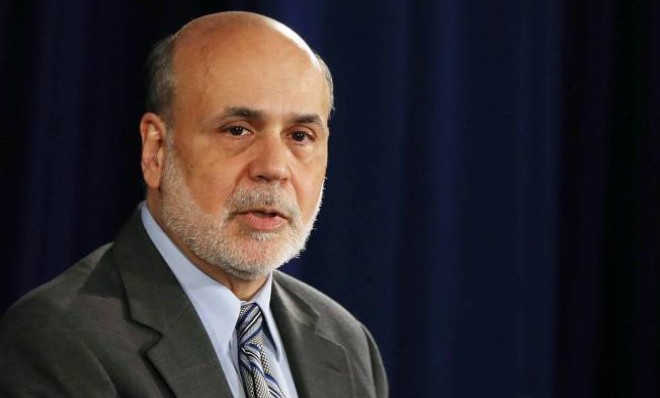

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke endorsed the idea of nixing the debt ceiling, saying, "It would be a good thing if we didn't have it." To prove his point, he compared it to a family's personal finances.

"This is sort of a family saying, 'We're spending too much, let's stop paying our credit card bill,'" he said. "That's not the way to get yourself in good financial condition."

Back in 2003, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan also suggested abolishing the "redundant" debt ceiling. And progressive House Democrats argued the same point when introducing a bill in January that would have gotten rid of the cap.

"Raising the debt ceiling does not allow one penny in new spending," Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.) explained. "It simply allows the government to pay the bills for spending that Congress has already authorized."

Since the debt ceiling is not in the Constitution, some have argued that the president could declare it unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment and ignore it altogether. House Whip Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) endorsed that approach as a last resort in the 2011 debt ceiling fight. It was "arguably [Obama's] power to do so," he said, and though legally dubious, it would be "better to take the action and find out later that perhaps he went beyond his authority but at least protected the credibility of the United States of America."

Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) this week raised the possibility again, saying, "I think the 14th Amendment covers it."

Indeed, the debt ceiling's only discernible purpose is to be used as a tool by the opposition party to extract demands, which in the GOP's case reportedly includes provisions that have nothing to do with government spending. And when that led to high-stakes budgetary hostage-taking in 2011, causing billions of dollars in economic damage and a downgrade in the U.S.'s credit rating, it revealed the debt ceiling as a "weird and destructive institution," wrote New York Times columnist Paul Krugman.

The debt ceiling does, at least, serve one practical purpose, politically speaking: It affords outraged lawmakers a peg to publicly fume about government spending.

In that way, the debt ceiling is "mere political theater," said Bruce Bartlett, a former adviser to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

"It is nothing but grandstanding for members of both parties to vote routinely for legislation that they know will create deficits and then profess shock and horror that the debt limit must be increased as a consequence," he said.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.

-

Political cartoons for February 7

Political cartoons for February 7Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include an earthquake warning, Washington Post Mortem, and more

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred