The nullification movement: How states aim to ignore federal gun laws

Both Democrats and Republicans have cited an odd precedent to flout Washington

Agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives are the federal government's primary enforcers of the nation's gun laws, tasked with regulating weapons in all 50 states. But if a new Missouri bill clears a gubernatorial veto and becomes law, ATF agents could soon end up being charged with felonies for simply doing their jobs.

Yes, the Missouri state legislature is on the verge of passing a bill that would nullify all federal gun laws, and make it a crime for U.S. agents to try to enforce them within the state's borders. The legislature will reconvene in September to vote on the bill, and it seems destined for passage.

Though it sounds far-fetched, Missouri is just one of many states that have looked for a way to circumvent Washington's gun laws and police the issue independently. Indeed, similar bills have been introduced in at least 37 states, according to ProPublica.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The legal rationale for such actions rests on a pre-Civil War idea called "nullification."

A quick history lesson: Back in the 1830s, South Carolina tried to ignore two federal tariff acts, declaring them unconstitutional. The state said they "violate the true meaning and intent thereof and are null, void, and no law, nor binding upon this State." President Andrew Jackson disputed that claim, and the state eventually backed down.

Yet South Carolina's legal argument has since been used by many states — and by lawmakers from both parties — to claim freedom from federal laws they find onerous or wrongheaded. For example, states have threatened to not establish the health-care exchanges mandated by the Affordable Care Act, and have legalized medical or recreational marijuana in direct defiance of the Justice Department.

Roughly four fifths of all states have passed some law in defiance of federal statutes, according to the Associated Press.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The difference in Missouri is that the bill would not only mandate that the feds have no authority over a given issue — in this case, guns — but also that federal agents could be prosecuted for trying to enforce federal laws. No state has sought to arrest federal agents for, say, enforcing the nation's drug laws, even though the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Justice Department have routinely raided medical marijuana dispensaries.

Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon (D) vetoed the legislation when it came to his desk earlier this year, calling it an "unnecessary and unconstitutional attempt to nullify federal laws." Yet the legislature is prepared to override his veto, a move that would result in Missouri enacting "the most far-reaching states' rights endeavor in the country," according to the New York Times' John Schwartz.

In 1996, California became the first state in modern times to directly defy federal law when it passed a resolution establishing medical marijuana dispensaries. In recent years, the idea of nullification has gained steam in Republican-controlled states as lawmakers there have looked for some way to shield themselves from federal gun laws.

In 2009, Montana passed the Firearms Freedom Act, which declared that federal gun laws did not apply to that state. A half dozen other states soon followed suit.

The gun law nullification effort intensified this year following the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre in Connecticut, as primarily red states, concerned that new federal gun legislation was on the way, sought to head off Washington. At least 20 states, including Wyoming, Texas, and Alaska, recently pursued such laws, according to Talking Points Memo.

In April, Kansas made headlines for passing a law called the "Second Amendment Protection Act," which exempted guns made in that state from all federal regulation.

Or at least it sought to do that.

Try as they might, states have little legal authority to nullify federal law.

The Supreme Court ruled on nullification in the 1950s, when states sought to resist integrating their school systems after the landmark ruling Brown v. Board of Education. In the 1958 case Cooper v. Aaron, the court ruled that states could not nullify federal law, citing a century-old declaration from Chief Justice John Marshall that, "if the legislatures of the several states may at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the Constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery."

Attorney General Eric Holder, responding to Kansas' law, issued a statement saying it "directly conflicts with federal law and is therefore unconstitutional." And last week, a federal court struck down Montana's Firearms Freedom Act, which had served as a template for other states pursuing nullification.

If Missouri's law does go through, it will almost certainly become entangled in an immediate legal challenge. So though the measure appears on its face to be a brazen attempt to supersede federal law and imprison dutiful federal agents, it may in the end amount to little more than a loud, symbolic nose-thumbing.

Jon Terbush is an associate editor at TheWeek.com covering politics, sports, and other things he finds interesting. He has previously written for Talking Points Memo, Raw Story, and Business Insider.

-

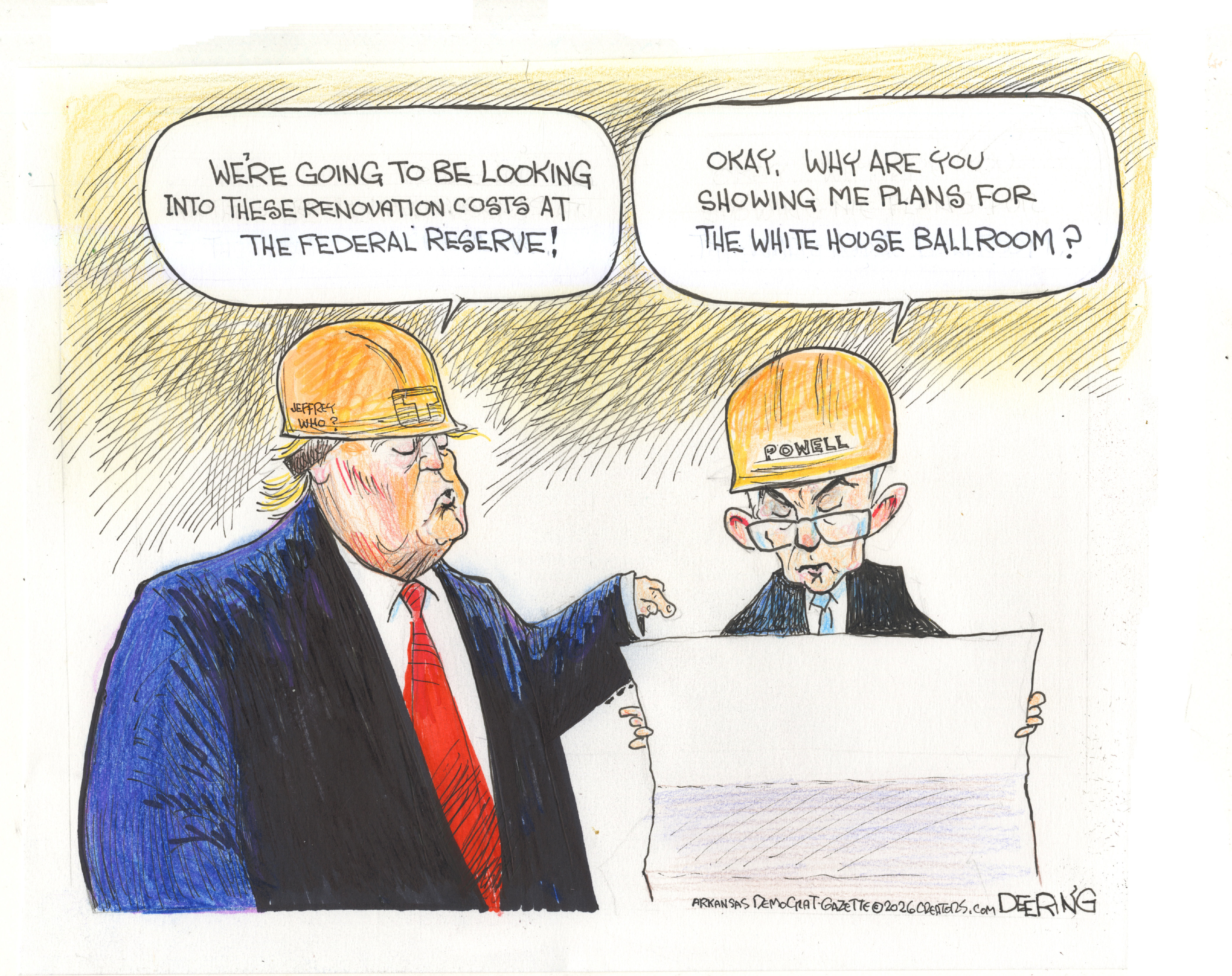

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred