5 disturbing historical practices you should never, ever try

Before you read these "how to" guides for foot binding and hara-kiri, take a moment to feel grateful that you live in the 21st century

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

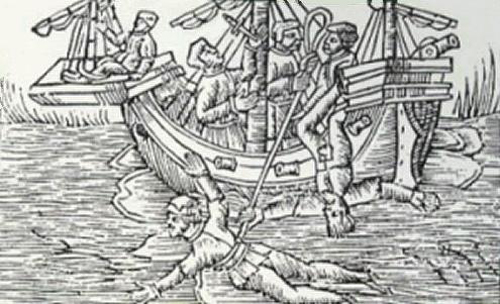

1. How to keelhaul

In the 1850s, a British ship and a French ship were anchored off the coast of the Mediterranean, refilling their water supply from a freshwater stream. A fight started between the two filling teams, as the British claimed the French were washing their clothes upstream, making the water undrinkable for the British. A French sailor struck a British officer, and for this he was keelhauled by his own crew. One of the British sailors recorded a first-hand account of the punishment. The offender was tied to a heavy grate, which itself was tied to two ropes, one on either side of the ship. The man was dropped into the ocean, allowed to sink, and then drug across the hull under the ship. This is what is known as a "keelhaul." The British crew insisted the French stop punishing the man, but the author records that the man "never recovered."

There are two options in a keelhaul. A short rope, which ensures you're shredded by the barnacles under the ship (seriously enough to tear limbs or decapitate), but makes the whole ordeal quicker. Or a long rope, which might spare you the deadly impact of the hull, but increased your chances of drowning.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

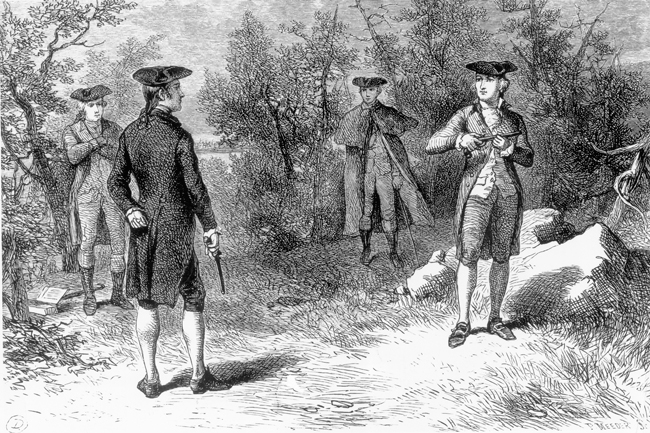

2. How to duel

A proper duel was meant to be a controlled exercise girded with structure and regulations. It was intended to prevent feuds, brawls, and other unnecessary bloodshed. Different cultures and eras had different rules, the most widespread being 1777's Irish Code Duello. Irish men were to keep a copy of it with their pistols, so that "ignorance might never be pleaded."

A duel starts with an insult. (Double points if you insult a lady under the care of the man you will duel with). If no apology is forthcoming, satisfaction is demanded and the duel is on. The Code Duello encourages apologies and reconciliation at almost all stages of the dueling process. Unless you hit someone. You can't apologize for that, you can only give him your cane and allow him to beat you if you want to avoid a duel.

The challenged may choose the weapon, unless the challenger swears he doesn't know how to use that weapon (usually a sword). The seconds, friends accompanying the duelers (primaries), are there to make sure rules are observed and to step in if necessary. They choose the time for the duel, prepare the weapons in sight of each other, and set the exact terms. The challenged chooses where the duel will be; the challenger chooses how far apart they will stand. Duels are not to be conducted at night, indicating a good sleep will help prevent hot headedness. If one man's nerves are unsteady, so that his hand shakes, everyone goes home and tries again tomorrow. After both men have shot an acceptable number of times (it varies depending on the offense) the seconds try to get them to reconcile. Death is not necessarily the objective. A lot depends on the kind of man you are dueling. President Andrew Jackson famously waited for the man who insulted his wife to fire a wild quick shot, which hit Jackson in the chest. Then, instead of deloping (firing into the ground, which although gentlemanly for a person of Jackson's status is forbidden in Code Duello), he took careful aim and shot the helpless man dead. If they can't reconcile, they stand their ground and fire at will.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

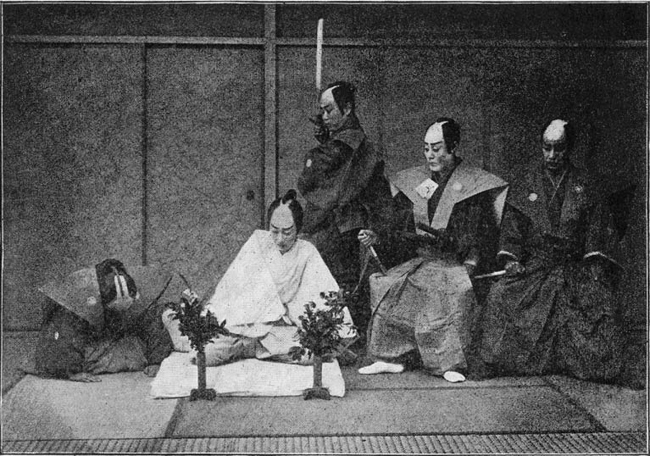

3. How to perform hara-kiri

At first, only honored Samurai warriors had the right to engage in the Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment and decapitation called hara-kiri. The first recorded act of ceremonial hara-kiri (or seppuku) came in 1180. It was an honorable form of suicide used to avoid capture, or a more dignified method of execution allowed for warriors who had committed crimes. Hara-kiri fell out of fashion as the years wore on, but was still used plentifully by high-ranking officials after Japan's defeat in World War II. It was, at its height, a respectable and involved ritual. He who was to perform it was fed a lavish dinner, wrote out his death poem, and prepared himself while wearing a special white kimono, all with the attendance of spectators.

Disembowelment is a horrible way to die. Luckily, it wasn't the actual cause of death in traditional seppuku. A man preparing for this ritual had a second, a trusted man who was an excellent swordsman. Or, in cases of capture, a respected warrior would receive the services of an equally respected warrior from the opposing side to act as his second. As soon as the warrior had driven the blade of the tanto, (a short sword with cloth tied around the blade to keep the man who held it from cutting his hand) into his own stomach, and made the traditional left to right cut, his second would decapitate him with the blow of a sword. Eventually some forms of the ritual bypassed the tanto altogether, allowing the second to strike his blow as soon as the doomed man reached for his ceremonial knife.

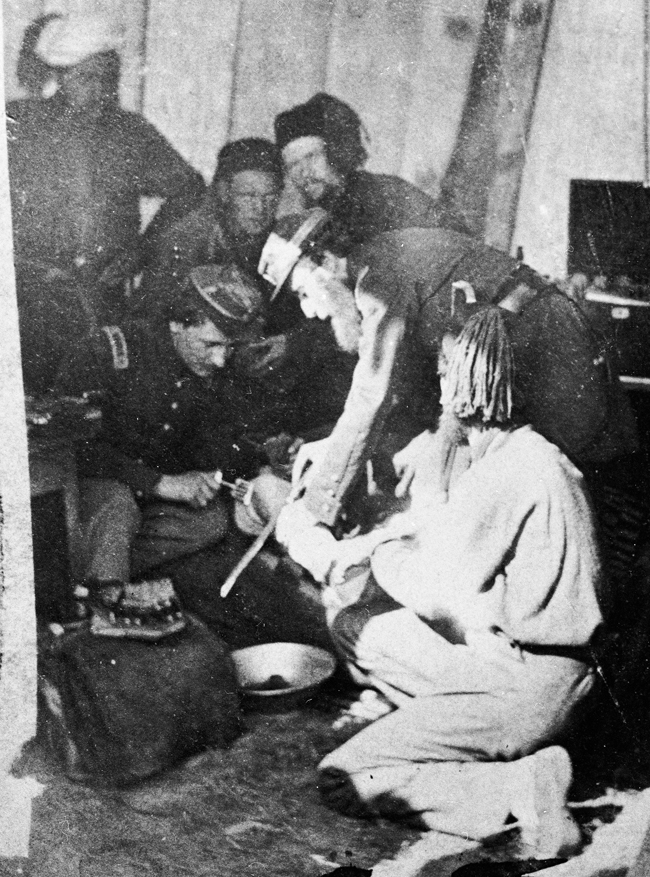

4. How to perform a Civil War field amputation

First of all, if you have yourself a nice bottle of antiseptic, some clean bandages, and some soap, you can really cut down on your required number of field amputations. Unfortunately, the doctors tending the wounded on Civil War battlegrounds did not know this. They had no concept of sterilization, germs, or the need for cleanliness (not that cleanliness was an option on a bloody battlefield). Bones were shattered by the heavy, slow-moving bullets of the day, tearing and infecting the flesh beyond repair. Wounds, even small ones, would turn septic, then gangrenous, and then the only way to save a soldier's life before the infection took over his body was to cut off the offending part.

First, wounded men would be triaged. Those most seriously wounded — shot through the head, belly, or chest — were set aside to die. There was nothing to be done for them. Soldiers wounded in extremities (which most were) still had a fighting chance. The doctor would clean the wound with a much-used but never-really-washed cloth, trying to remove shrapnel, cloth, and bone fragments.

The patient would be chloroformed. A tourniquet would be applied above the cut to control blood loss. Then incisions would be made around the leg, through the skin and muscle, leaving a flap of extra skin to cover the eventual exposed tissue. When the scalpel hit bone, the surgeon would change over to the bone saw, hack through the limb, and toss it on the pile with the rest. His attendants would stanch the severed arteries, binding the wound with horsehair, silk, or cotton threads. The surgeon would close the wound with the extra flap of skin, leaving a hole for drainage. It could be done in 10 minutes by a good surgeon. The patient was then left to survive any number of infections resulting from his unsterilized, unsanitary, but occasionally lifesaving procedure.

5. How to bind your feet

There was a time in China when, if you were a good mother, and if you cared about your daughter's future, you would cripple her. Chinese foot binding, the process of folding a girl's foot into a fist shape over the span of her childhood to make an exceptionally tiny foot as an adult, began in the 10th century and was banned in the 20th. Mothers would begin the painful process, folding the toes in toward the bottom of the foot and securing them with bandaging, from the time a little girl was 2 years old. An especially kind mother would begin the process in winter, as cold feet feel less pain. The foot was soaked to soften it, and the nails closely cut to prevent ingrowing. The child's mother would break her toes, (and eventually her arch), and bind them tightly to the sole of the foot. As the girl grew her bandages were removed, the foot cleaned, and then re-bandaged tighter. Bandages were wrapped in a figure "8" that would draw the heel and toes as close together as possible.

The result of this, when the woman reached adulthood, were what looked like tiny little doll feet, on the outside. On the inside, there was (fair warning before you click!) terrible deformation, necrosis, and infection.

Mothers did this because it ensured their daughters a better future. A wife with tiny bound feet was a showpiece. She was elegant and delicate. She could not do labor because of her feet, which separated her from common women.

Communism dealt the final official blow to foot binding, as health and hard work became associated with happiness instead of peasantry.

Therese O'Neill lives in Oregon and writes for The Atlantic, Mental Floss, Jezebel, and more. She is the author of New York Times bestseller Unmentionable: The Victorian Ladies Guide to Sex, Marriage and Manners. Meet her at writerthereseoneill.com.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?Today's Big Question The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?