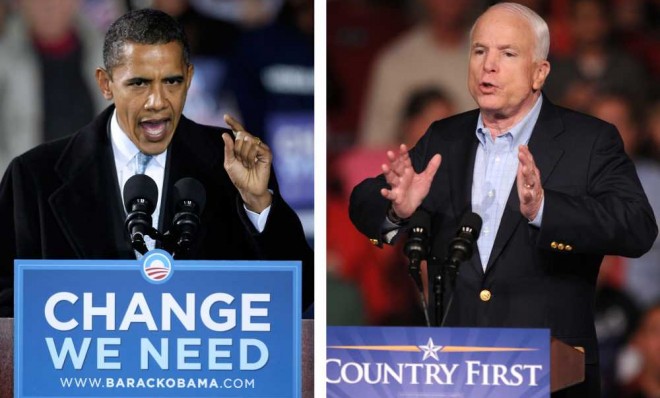

Will John McCain save Obama's second term?

Obama's 2008 rival has spent years battering the administration's agenda. But all of a sudden...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) lost the presidency to Barack Obama in 2008, he spent the next four years in a colossal pout. Abandoning his previously held "maverick" positions, a newly partisan McCain helped filibuster immigration reform and campaign finance reform. He violated his own pledge to oppose filibusters of judges except in extraordinary circumstances. He refused to participate in negotiations for a bipartisan bill to avert a climate crisis, despite having recently co-sponsored such a bill with one of the negotiators. And he greeted Obama's second-term by leading the fight to prevent Susan Rice from being selected to serve as secretary of State.

But now, McCain may be the linchpin to Obama's second-term success.

This week he sealed the deal to end Republican obstruction of presidential nominees that had been hamstringing the work of the National Labor Relations Bureau (NLRB) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid exulted, "John McCain is the reason we're at the point we are … No one was able to break through but for him."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Last month he played a major role in shepherding bipartisan immigration reform through the Senate, and he is keeping pressure on his Republican House colleagues by publicly warning them of political disaster if they fail to follow suit. When the initial compromise was struck, Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer singled out McCain: "His wisdom, his strength, his courage, his steadfastness and many other adjectives that I'll skip at the moment, have really been inspiring to me and, I think, to all of us."

Less successfully, he supported the bipartisan deal to expand background checks for gun purchases. His support wasn't enough to overcome a filibuster, but the chance remains for another legislative push before the end of the term.

Beyond dealmaking, McCain has been rhetorically lashing out at right-wing libertarian members of his party for failing to be constructive, both when refusing to allow formal budget negotiations to occur and when attacking the president's counterterrorism policies.

Even when McCain is antagonizing Obama, he's helping. McCain ramped up the fight to filibuster Defense Secretary nominee Chuck Hagel, then called it off. He accused Obama of a "cover-up" in the Benghazi matter, then refused to back impeachment. He puffs up right-wing outrage bubbles, then pops them.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the deals are where McCain may prove to be Obama's biggest second-term ally. By ending Republican obstruction of NLRB appointments, the agency can put behind the constitutional questions around the president's earlier recess appointments that had left recent NLRB decisions in legal limbo, frustrating both workers and employers. And a fully functioning NLRB gives Obama a renewed opportunity to strengthen worker rights that have been degrading for decades.

By ending Republican obstruction of Obama's choice to run the CFPB, Republicans abandoned their last ditch effort to nullify this cornerstone of Obama's financial reform law, allowing Obama to lock down new bank regulations that could prevent future market meltdowns.

And if immigration reform does eventually clear the House and reach the president's desk, McCain will have facilitated what may become Obama's biggest second-term legislative victory, ending the underground economy of second-class citizens.

Why exactly McCain has shifted his posture in Obama's second-term we may never know, but it's certainly rational. To remain bitter until the end of his Senate career would have rendered McCain as little more than a sad footnote in history. But to shake off his 2008 defeat and work with the president on issues he's long cared about gives McCain the chance to be one of the most consequential senators (and defeated presidential nominees) in history.

And if McCain really wanted to seal his place in history, he might think about restarting those climate talks.

Bill Scher is the executive editor of LiberalOasis.com and the online campaign manager at Campaign for America's Future. He is the author of Wait! Don't Move To Canada!: A Stay-and-Fight Strategy to Win Back America, a regular contributor to Bloggingheads.tv and host of the LiberalOasis Radio Show weekly podcast.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred