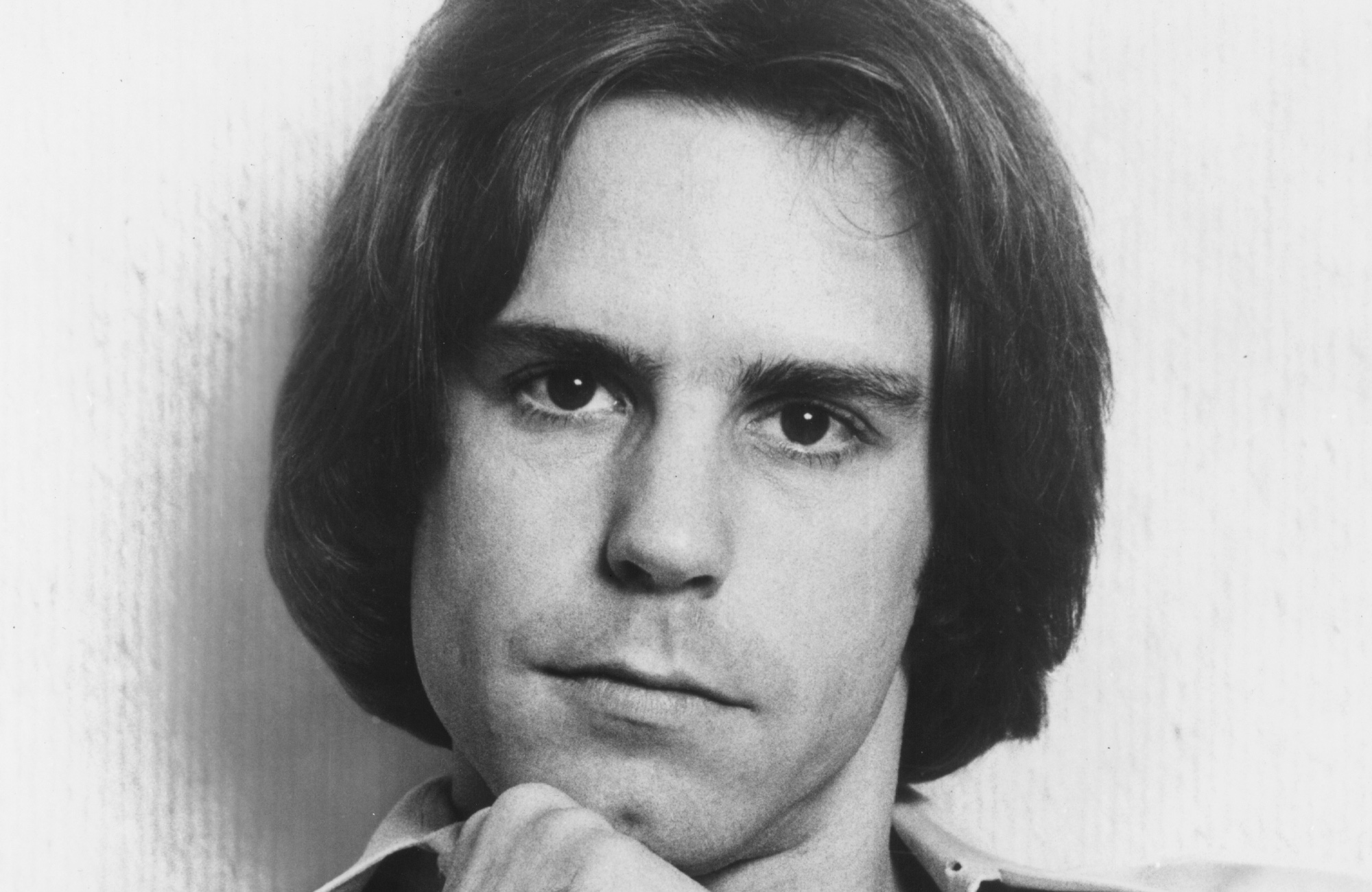

Douglas Engelbart, 1925–2013

The computer visionary who invented the mouse

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Douglas Engelbart set the computing world on fire in December 1968. Standing in a San Francisco conference hall filled with the nation’s top computer experts, he unveiled the pioneering technologies his experimental research group had been pursuing for the past decade at California’s Stanford Research Institute. Engelbart demonstrated such innovations as word processing, video conferencing, and desktop windows—13 years before the debut of the first IBM personal computer. He also showed how a mouse, which he’d invented four years earlier, could be used to control a computer. “People were amazed,” said fellow Stanford engineer William English. “In one hour, he defined the era of modern computing.”

Born in Portland, Ore., Engelbart became hooked on technology as a high school student during World War II when he heard about radar—a technology so secret that, rumor had it, the U.S. Navy kept its instruction manuals locked in a vault. “It all sounded so dramatic,” he recalled in 1986. He interrupted his studies in electrical engineering at Oregon State College to serve as a radar operator in the Philippines. After the war he finished his undergraduate degree in Oregon and then got a Ph.D. from the University of California at Berkeley before joining Stanford in 1957. At a time when computers were the size of Buicks—and most of the humans interacting with them were scientists—Engelbart foresaw that this technology could help ordinary workers cooperate better to make the most of available information, said Time.com. “Then he set about building the necessary tools to make that not only possible, but also easy.”

With the user in mind, his research team developed much of the technology that now underpins the Internet, including hypertext, which links digital files. Engelbart’s most famous invention, the mouse, was a product of necessity. After building an $80,000 monitor, he “figured he needed a device to interact with the screen,” said The Washington Post. Working with fellow engineer English, he developed a thick wooden block that rolled around on a desktop on metal wheels and connected to the computer via a cord. The device’s official name was the “X-Y Position Indicator for a Display System,” but Engelbart’s lab called it a “mouse” for its tail-like cable. “We thought that when it had escaped out to the world it would have a more dignified name,” said Engelbart. “It didn’t.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although his work inspired generations of scientists, and was later used by Microsoft’s Bill Gates and Apple’s Steve Jobs in building their computer dynasties, Engelbart never became rich or a household name, said the Los Angeles Times. He received no royalties for the mouse, which had been patented by Stanford and later licensed to Apple, and in later years struggled to get funding for his research. “He wanted to help people solve problems, and he saw the world as having very significant problems,” said technology writer and critic Howard Rheingold. “That is not something you can get a patent on, start a company, or make a fortune on.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s Wife

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s WifeIn the Spotlight Trollope found fame with intelligent novels about the dramas and dilemmas of modern women

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

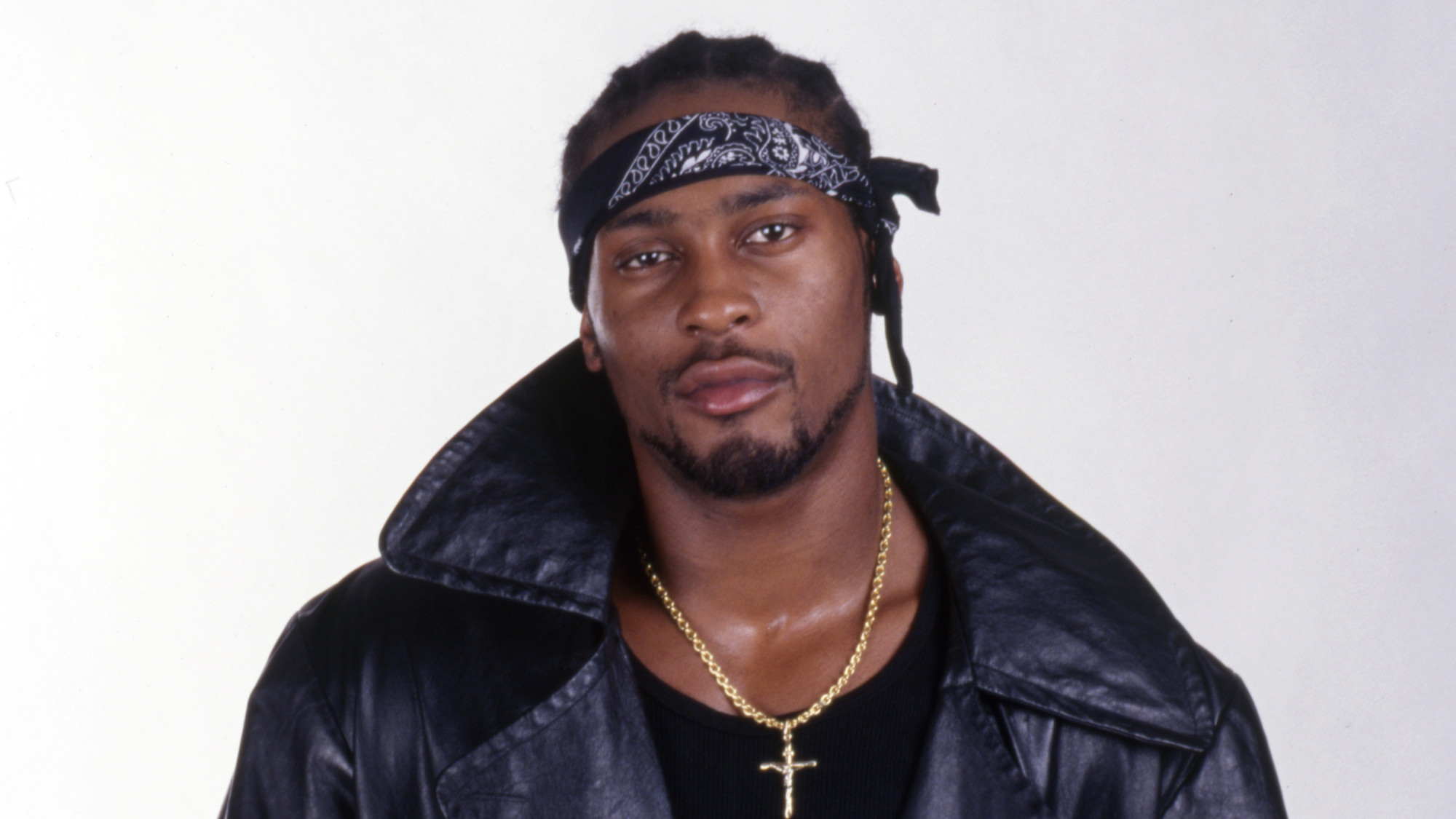

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

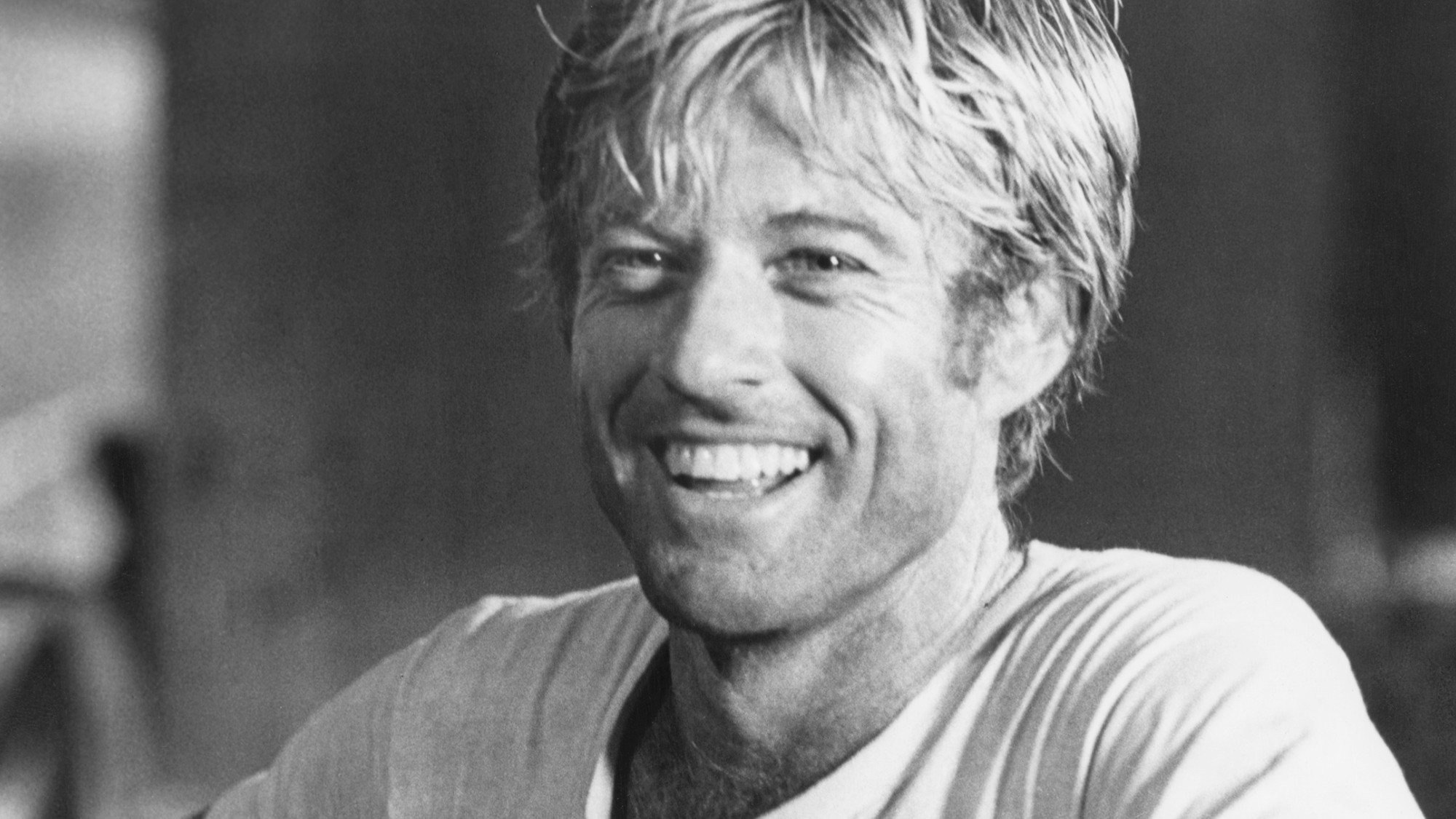

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance