Giulio Andreotti, 1919–2013

The perennial prime minister who mastered Italian politics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Giulio Andreotti’s first brush with power came at age 8, when he slipped past security guards during a tour of the Vatican and had an impromptu audience with Pope Pius XI. He would go on to spend 60 years in the Italian parliament, and to serve as prime minister seven times—a political record that led supporters to call him “the Eternal Giulio.” His enemies preferred another nickname: “Beelzebub,” an agent of darkness.

It was also at the Vatican that Andreotti made his first political ally, said BBC.com. As a student in 1938, he met veteran politician and anti-Fascist leader Alcide De Gasperi while searching for a book in the Vatican library. The chance meeting prompted Andreotti to “remold his life.” He became active in student politics and was named an aide to De Gasperi when he became prime minister in 1945. Andreotti became a junior minister in De Gasperi’s Christian Democratic government at 28 and, as a pillar of the party’s right wing, held almost every cabinet post over the following two decades. He first became prime minister himself in 1972.

Andreotti ruled the country as the “ultimate insider of Italian political life,” said The Guardian (U.K.), enjoying the implicit trust of the Vatican, Italy’s upper classes, and the powerful civil service. As the leader of a weak center-right coalition in 1972–73, he helped steer a country rocked by domestic terrorism and organized crime. He later helped secure a deal to bring the Communist Party into government from 1976 to 1979—an alliance that polarized Italy but kept the Christian Democrats, and Andreotti, in power.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It was during this period that “the most traumatic event” of Andreotti’s life took place, said The New York Times. The Red Brigades, a left-wing terrorist group, kidnapped former Prime Minister Aldo Moro—a friend of Andreotti’s who was also a political rival—and demanded its leaders be freed from jail in exchange for Moro’s life. But Andreotti’s government “did not budge from its resolve not to deal with terrorists.” When Moro’s bullet-ridden body was discovered in May 1978, many accused Andreotti of acting out of political spite in refusing to barter for Moro’s life.

Andreotti’s final premiership ended in 1992, as his party became “discredited by fast-unfolding corruption scandals,” said the Financial Times. Andreotti was charged the following year with consorting with the Mafia. Despite evidence from over 30 former mafiosi, he was acquitted in 1999 of rigging trials and covering up Mafia activities in Sicily. Prosecutors kept trying to pin Mafia charges on him, said Businessweek.com, but after a series of failed indictments and trials, it was the Moro affair that “came back to haunt Andreotti.” He was found guilty in 2002 of ordering the 1979 assassination of a journalist who had been preparing to publish excerpts from a diary Moro wrote in captivity, detailing Andreotti’s extensive ties to organized crime. The conviction was overturned on appeal, but the damage was done; Andreotti’s only remaining ambition, to “wrap up his political career as president of the republic,” would remain unfulfilled.

Andreotti was a quiet, fiercely private man with a fervent Catholic faith and a reputation for asceticism, but he could be witty. When asked by a journalist if he would ever grow weary of power, Andreotti’s response became a famous aphorism of Italian politics: “Power,” he said, “tires only those who don’t have it.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

9 products to jazz up your letters and cards

9 products to jazz up your letters and cardsThe Week Recommends Get the write stuff

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

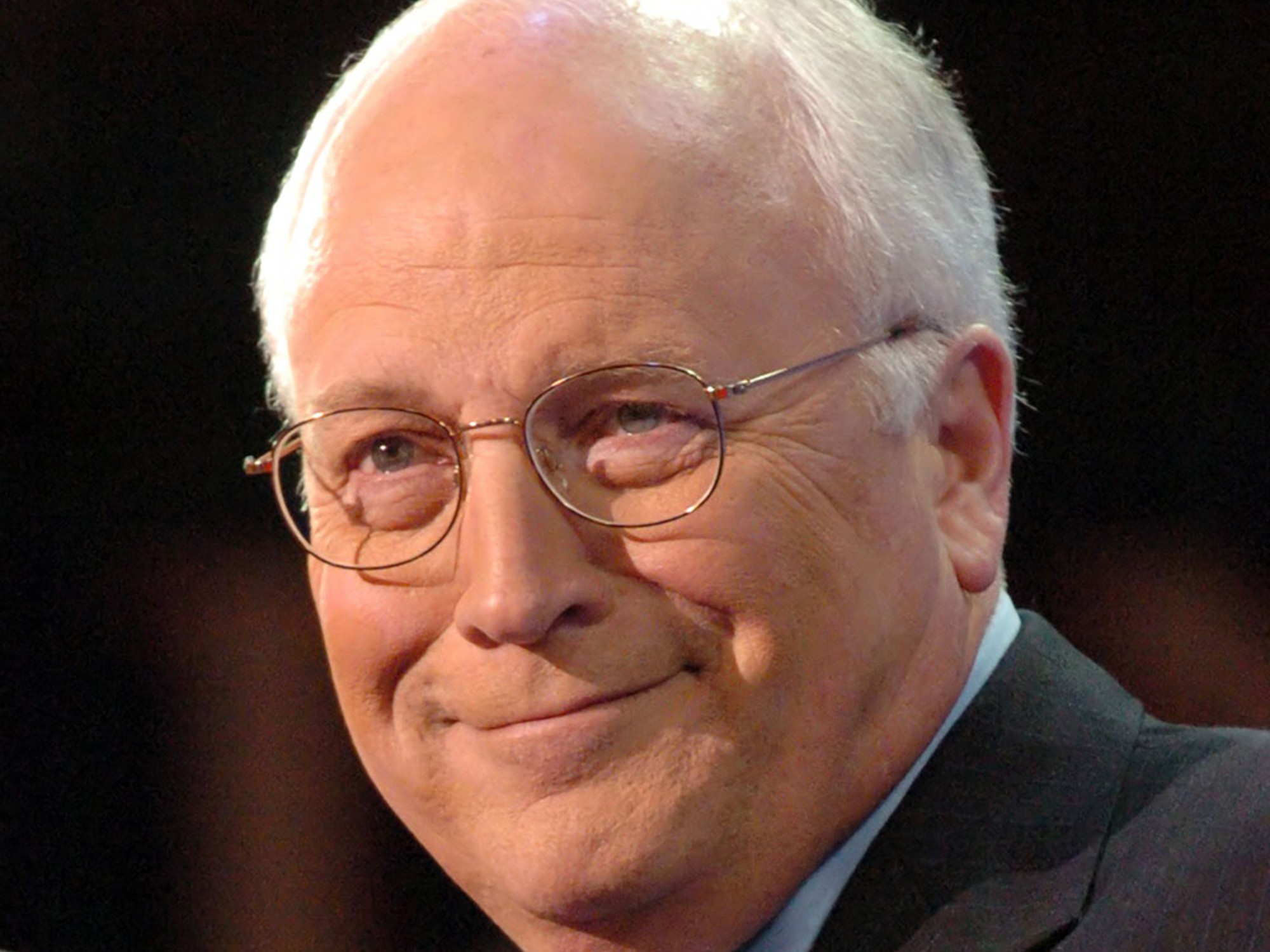

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terror

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terrorfeature Cheney died this month at the age of 84

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

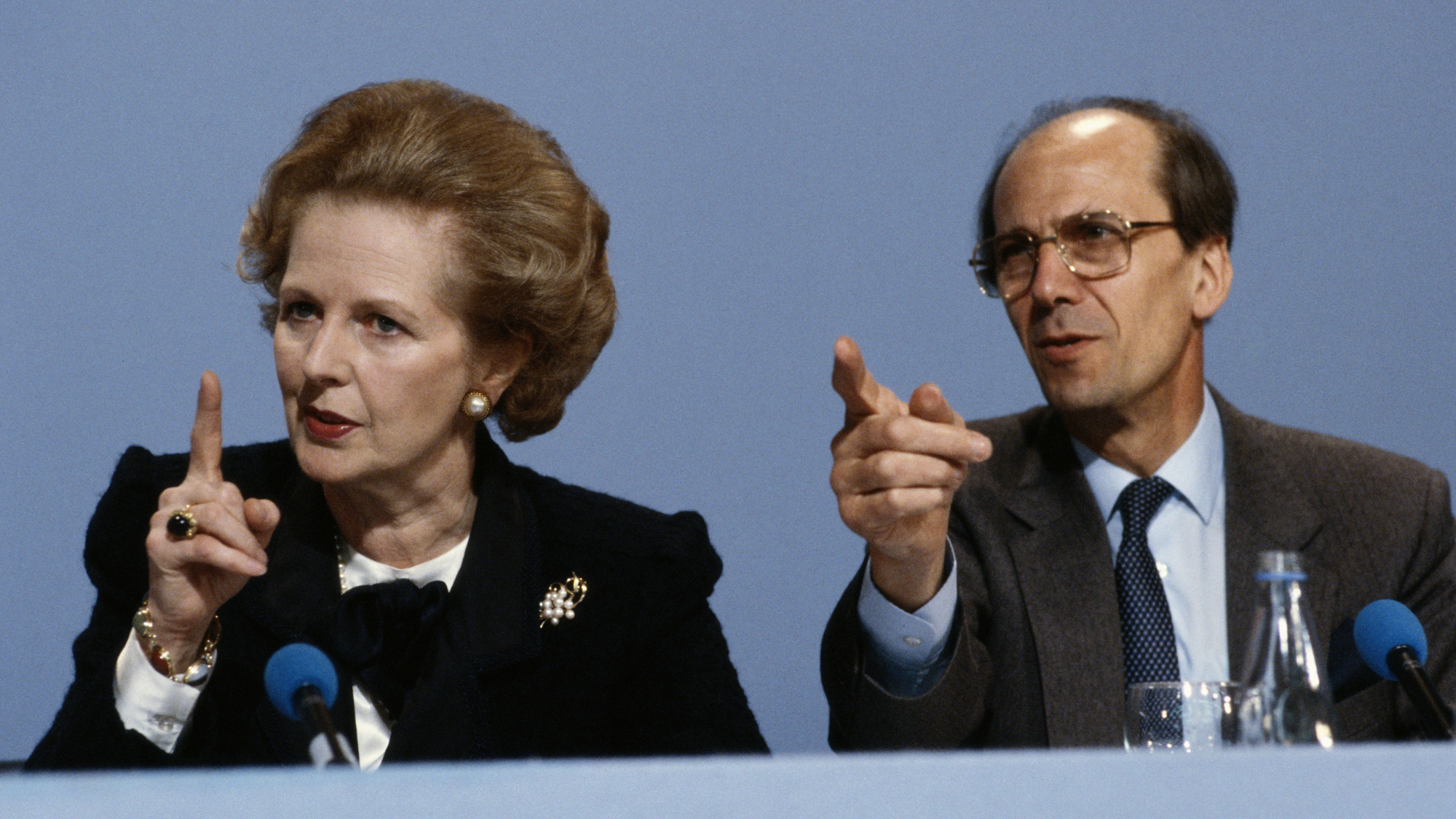

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcer

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcerIn the Spotlight Former Conservative Party chair has died aged 94

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't