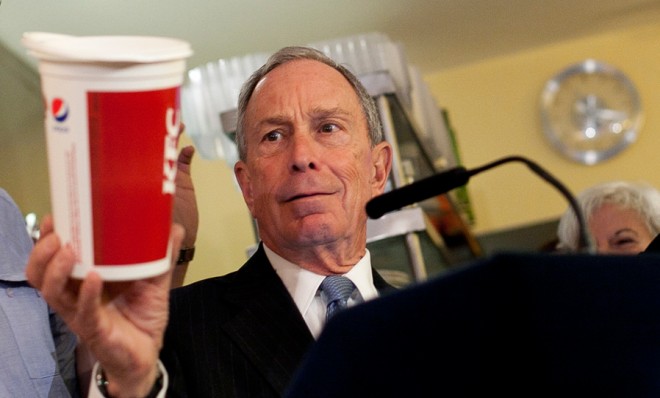

From soda to guns: Michael Bloomberg's hubris, and the politics of prohibition

Hizzoner has overreached — big time

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg is one of the brightest and most ambitious political leaders in the United States. He has strong and thoughtful views on obesity — which is indeed one of the central threats to the health of Americans, as well as the fiscal health of their country — and gun control — which is a problematic and perplexing issue in major metropolitan areas. Bloomberg also has the resources to get his message out.

Unfortunately, bright people can and often do lack the political instincts needed to sell their ideas beyond the groups of people inclined to support them in the first place.

Over the last decade, Mayor Bloomberg has transformed himself from a politician dedicated to protecting and empowering consumers to make healthier, better choices into a self-absorbed lecturer hell-bent on forcing consumers to make the right choice. Mayor Bloomberg's hubris has threatened his own legacy as a public-health pioneer, and has shifted his public persona from thoughtful reformer to wannabe administrator of the Bloomberg nanny state. Whether the issue is soda pop or firearms, this shift in public perception has real consequences for the mayor's ambitious agenda, and his legacy as he nears the end of his third and final term.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It all started so well. From his first day in office, Bloomberg dedicated real effort to using laws to improve public health. In 2002, Bloomberg banned public smoking in the city's bars and restaurants. In 2005, he made New York the first city in America to pass a trans fat ban. Then, in 2008, Bloomberg took the very reasonable and important step of forcing fast food restaurants to post calorie counts on menus.

These three measures represent the best of Bloomberg. By banning smoking inside restaurants, Bloomberg protected patrons from being unwillingly exposed to secondhand smoke in a confined environment. The trans fat ban was a quality protection measure. Finally, the calorie count requirement represents the highest and most appropriate use of government: providing the consumer with information so that they can choose what to eat and drink based on a full picture of the costs and benefits.

In 2010, though, Bloomberg shifted from protecting and empowering consumers to coercing them. He lobbied to bar the use of food stamps to purchase sodas (it failed for enforcement reasons) and he urged state legislatures to make it more expensive for consumers to purchase sodas by taxing sodas with sugar (that failed, too). In 2011, the mayor banned smoking in most outdoor areas.

Whereas providing people with calorie counts gave people the information to make better decisions, the soda tax proposal aimed to punish "bad" decisions. Similarly, where the indoor smoking ban sought to protect "captive audiences" (non-smokers trying to have dinner indoors) from immediate exposure to secondhand smoke, the outdoor smoking ban aimed to make it harder for people who choose to smoke to actually do so.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Big Gulp ban, recently enjoined by a New York Supreme Court Judge, moves the next step up the ladder of coercion. Whatever one thinks of the legality, when viewed alongside the 2011 outdoor smoking ban, the legislation makes clear that the mayor has dramatically altered his leadership philosophy. Once content to empower and protect consumers, Bloomberg became impatient. Looking for a more efficient means to bring about his desired end, the mayor shifted away from his previous strategy of legislatively influencing outcomes and instead turned to downright coercion.

Telling people they cannot do bad things is more efficient than arming them with the information to make good choices. But citizens view the two types of legislation very differently, and the further the mayor's legislative agenda moved along the spectrum of coercion, the more the public has begun to wonder whether the mayor was helping them or imposing his preferences upon them.

Bloomberg's hubris extends beyond his efforts to govern (or rule) the greatest city in the world. He has also emerged as an outspoken advocate for firearms restrictions. But while Bloomberg may well have ideas worth talking about, his infatuation with the sound of his own voice and his overwhelming desire to be the public face of the anti-handgun movement in the U.S. has made it less likely that anything resembling his vision for a handgun-free America will prevail.

Bloomberg, surrounded by people with similar views, appears to have fallen victim to the same echo-chamber effect that left so many conservatives utterly confused when Barack Obama crushed Mitt Romney in November. When you only talk to people who agree with you, it becomes easy to mistake your own view for the view of the majority of Americans. As a result, Bloomberg has used his position and his public profile to castigate anyone who has ever even considered opposing the gun control measures he has proposed.

Now Bloomberg has all but demanded that the president and Congress undertake an aggressive reform agenda, critics be damned. In other words, he wants to impose restrictions on gun owners rather than work to reach a compromise with them. That has failed. Even modest gun control measures appear unlikely to pass.

Bloomberg's rhetoric on guns was not only too accusatory and aggressive, but he was also the entirely wrong messenger. The vast majority of gun owners, and indeed, the vast majority of Americans, do not live in New York City and are not inclined to take orders from its arrogant mayor.

But the greater lesson is more broadly applicable. Mark Twain said it right:

Nothing so needs reforming as other people's habits. Fanatics will never learn that, though it be written in letters of gold across the sky. It is the prohibition that makes anything precious.

Jeb Golinkin is an attorney from Houston, Texas. You can follow him on twitter @jgolinkin.