What today's GOP could learn from Benjamin Disraeli

The 19th-century British lawmaker paved the way for decades of conservative dominance

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"We must stop being the stupid party." So Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal told Republicans assembled at the winter meeting of the Republican National Committee last week. Breaking the stupidity habit, Jindal continued, means more than avoiding unforced errors like Mitt Romney's 47 percent remark or Todd Akin's reflections on gynecology. Although Jindal's speech was remarkably light on details, the governor argued that Republicans have outright failed to appeal to the problems and perspectives of most Americans.

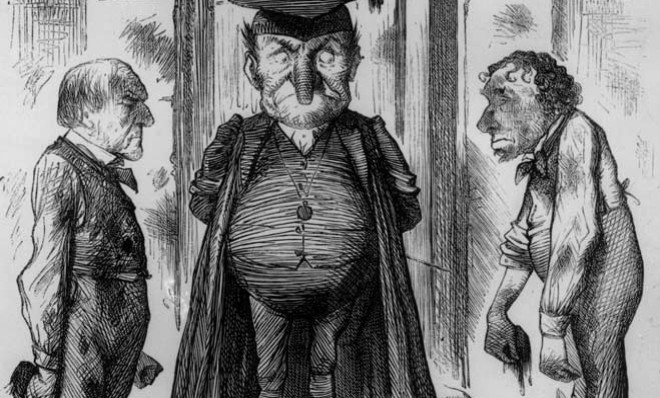

By describing the GOP as "the stupid party," Jindal evoked the British philosopher John Stuart Mill. In 1866, when he was serving in Parliament, Mill confidently asserted that "the Conservative Party was, by the law of its constitution, necessarily the stupidest party." What Mill did not know was that Conservatives would, within a few years, be transformed from a reactionary rump into Britain's natural party of government.

Jindal and other Republican reformers could learn something from the mastermind of this transformation: Benjamin Disraeli. Although his times were different than ours, Disraeli provides a model of how conservatives can learn to win in a changed country.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Disraeli's accomplishment is more easily appreciated if we consider the Conservative Party at the time of Mill's statement. Although several Conservatives served as prime minister in previous decades, the party had not won an absolute parliamentary majority in years. The basic reason was its hostility to electoral reform. After the 1832 Reform Act increased the number of middle-class voters and eliminated "rotten boroughs" controlled by great landowners, the Conservative base among the rural gentry was seriously outnumbered.

The problem was exacerbated in the 1840s, when Prime Minister Robert Peel led pro-free trade Conservatives into a coalition with the opposition Whigs. With the exception of Disraeli and his patron, the Earl of Derby, almost all the party's luminaries followed Peel into the alliance that became the Liberal Party. The Conservative bench was so empty that the short-lived government Derby formed in 1851 was dubbed the "Who? Who?" cabinet in imitation of the Duke of Wellington's response to the members' names.

The Conservatives' situation hadn't improved much by the time of Mill's remark. In 1866, they were working against another reform bill, this one extending the franchise to what we would now call the lower-middle class. Led by Disraeli in the House of Commons, the Conservatives managed to defeat the bill despite its popularity with the public. Too small to govern but unwilling to compromise, the Conservatives looked like the Victorian "Party of No".

But opposition to reform in 1866 was just the first stage in Disraeli's strategy to revive Conservatism. The following year, Disraeli successfully introduced his own bill, which extended the franchise even more broadly than the previous proposal. Rejecting Conservative resistance to mass democracy, Disraeli argued that not only should the people be allowed to vote, but that they would vote Conservative if given the chance. It was a revolutionary argument at the time. It was also correct.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Disraeli was proved right in the election of 1874, which yielded the first Conservative majority in nearly 30 years. Serving as prime minister with his own mandate, Disraeli secured passage of pioneering measures for improving public health and increasing workers' rights. For Disraeli, these measures had nothing to do with hostility to wealth. Inspired by Romantic conservatives like the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, he believed that the "Two Nations" of the rich and the poor could only be reconciled when the privileged few accepted responsibility for the welfare of the many.

This belief had a utopian aspect. But Disraeli was correct that workers and small-business people preferred cooperation with an elite that showed concern for their welfare to the harsh laissez-faire associated with 19th-century liberalism. What's more, Disraeli did not hesitate to base this alliance on religious affinity. In Victorian Britain, both the working class and gentry tended to be members of the Church of England, while entrepreneurs were disproportionately members of dissenting churches.

Disraeli's domestic populism was accompanied by renewed activism around the world. Disraeli, more than any other politician, deserves credit for the transformation of Britain's ramshackle collection of dependencies into a formal empire. His pursuit of international prestige was mocked by Liberals. But it was exceptionally popular with new voters enfranchised by his reforms — and managed to secure most of Disraeli's aims without war between great powers.

Indeed, the revitalization of the Conservative party with a base in the "respectable" working class, rather than any specific policy, was Disraeli's greatest achievement. Disraeli's sustained term in office lasted only six years, from 1874 to 1880. But Conservatives were the government for much of the next century — and beyond.

So: What lessons can Republicans today draw from Disraeli's career?

Number one: Successful parties seek popular majorities rather than clinging to procedural advantages. From the early stages of his career, Disraeli argued that Conservatives had to show that they represented "one nation" rather than a single class whose influence was exaggerated by unequal representation. In the present context, that means Republicans should reject attempts to rig the electoral college in their favor. Gaming the system may help win the next election, but it will never win a mandate.

The second lesson: Republicans must show that they care about solving the problems faced by voters outside the most comfortable classes. In addition to developing credible responses to wage stagnation and unemployment, that means helping Americans acquire and keep health insurance, and make safe investments for their retirement. As I've argued before, Republicans should reform Social Security and Medicare with the aim of preserving, not privatizing, them. The idolatry of market forces that such proposals reflect is historically rooted in Mill's utilitarianism rather than in traditional conservatism.

Finally, Republicans must retain their assertive nationalism, which resonates with what Walter Russell Mead describes as the Jacksonian tendency in American politics. Nevertheless, they should learn to temper it with prudence. Disraeli was among the 19th century's most outspoken advocates of "British exceptionalism". At the same time, he recognized that other nations are also proud of their achievement and traditions — and that Britain could often achieve its aims by cultivating common interests rather than hectoring or bullying. The same is true of the United States.

A Republican Party that learned Disraeli's lessons would still be recognizably conservative. But it would be a governing party with the potential to appeal to voters in a variety of demographics and regions. Hope for an American counterpart to Disraeli's "one nation" Conservatism may seem anachronistic. It shouldn't — because it's essentially the triumphant Republicanism of Nixon and Reagan under an unfamiliar name.

Samuel Goldman blogs for The American Conservative. Follow him on Twitter: @swgoldman.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred