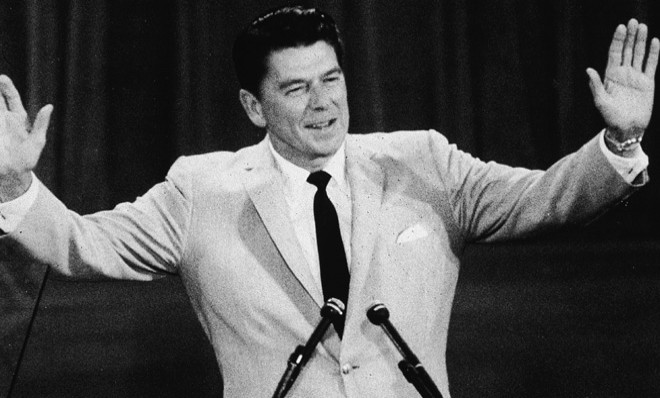

When Ronald Reagan (sort of) fought for the dignity of gays

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it came to AIDS, Ronald Reagan was far too late and billions of dollars short. That much is clear, as even a charitable rear-view-mirror-look at the history of the epidemic would show. No question that many of Reagan's top political aides held an animus for gay people. As the new documentary history of the ACT Up movement makes clear, a lack of political leadership was only one of the reasons why it took the medical community to take the "gay plague" so seriously.

But Reagan himself was not an instinctive homophobe. While not a gay rights activist, he was ahead of many in his party in attempting to treat the gay men that he knew with dignity.

This I learned from a great and overlooked book about the great politico-journalistic rivalry between Richard Nixon and Jack Anderson. Mark Feldstein's Poisoning The Press is a good reminder for those of us who hold Anderson as a hero muckracker. He paid his sources. He took bribes not to print stories. He knowingly advanced the causes of his allies. And he hated homosexuals.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In late 1967, as many Republicans looked to the governor of California, the actor named Ronald Reagan, for political guidance, Anderson and his boss Drew Pearson published a column about a "homosexual ring" operating in the governor's office. Eight men close to Reagan, the column wrote, had an orgy in a Lake Tahoe hotel room. The story was, as Feldstein notes, more or less true, although only two of the men were part of Reagan's inner circle. They were Phil Battaglia, his chief of staff, and a scheduler, Richard Quinn.

The story might never have amounted to anything had Reagan himself not felt outraged. He was not outraged by the conduct of his staffers, although he had, upon the urging of his political advisers, let them retire well before the story came out. He was incredulous that a newspaper would find the subject of the sex lives of rather anonymous citizens to be worth the newsprint. California newspapers, Feldstein wrote, held back from printing the column. But Reagan decided to hold a press conference so he could deny it. The denial was a lie, as Reagan acknowledged at a subsequent press conference after the news of the two men's firing had come to light. But Reagan said his "credibility gap" came from his unwillingness to "destroy human beings."

Of course, it was Reagan himself who agreed to fire the two men in the first place, and whose sense of outrage caused their outing. His good intentions aside, he was pretty much complicit. But his instincts were decades ahead of their time. It's not surprising: He came from Hollywood. Who leaked the story to Anderson? Feldstein says it was Lynn Nofziger, one of Reagan's aides, who had hoped to precipitate a different response. He wanted the scandal to serve as a predicate for house-cleaning to get every gay person away from Reagan, and to cause Reagan to act so forcefully against the gays in his midst that there would be no suspicion that Reagan himself was gay.

That backfired too. Reagan was weakened by the confusion. Richard Nixon exploited the controversy by seeding doubts about Reagan's true conservative credentials in the minds of activists. Reagan and Nixon would both have their presidencies.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ironically, Reagan would have a chance to partially redeem himself before his.

If you've watched Milk, you know the story: In 1978, when California was on the verge of passing a state ballot initiative that would ban openly gay teachers, it was Reagan's opposition that changed public opinion. He had been lobbied to weigh in by several gay rights activists. And so he did. Which, if you think about what he was trying to do in 1978 — win over conservatives — was pretty ballsy.

Judged alongside his record on AIDS, Reagan was no saint. (There's plenty of evidence that he never truly understood what was happening because his White House shielded the truth from him, but that's an aside, not an excuse.)

Still, it makes him, to me, a more interesting and complicated president than his caricature.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.