The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you handle an object, you leave your fingerprints all over it. When that object is examined closely, your identity can be easily revealed. In a way, the same is true when you write something. Every individual has what linguists call an idiolect: a personal dialect, or a sort of verbal fingerprint left behind in the form of your preference for certain words, phrases, and grammar. Sometimes, these linguistic profiles can help identify an anonymous author.

No doubt internet sleuths have studied the language of an anonymous op-ed in The New York Times to identify the unnamed Trump administration official who penned it claiming to be part of the "resistance." Some think the word "lodestar" is a linguistic smoking gun, suggesting Vice President Mike Pence could be the author, because he's used the word in the past.

But, perhaps unsurprisingly, personal dialect forensics is not nearly this simple.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There are numerous examples from history of language being used to trace someone's identity. In 1887, several letters were published purporting to show that the Irish nationalists led by Charles Stewart Parnell supported violence. But a dramatic cross-examination revealed the letters had been forged by a man named Richard Pigott, a former supporter of Parnell. When asked to write the word "hesitancy," Pigott misspelled the word as "hesitency," which had also been misspelled in the letters.

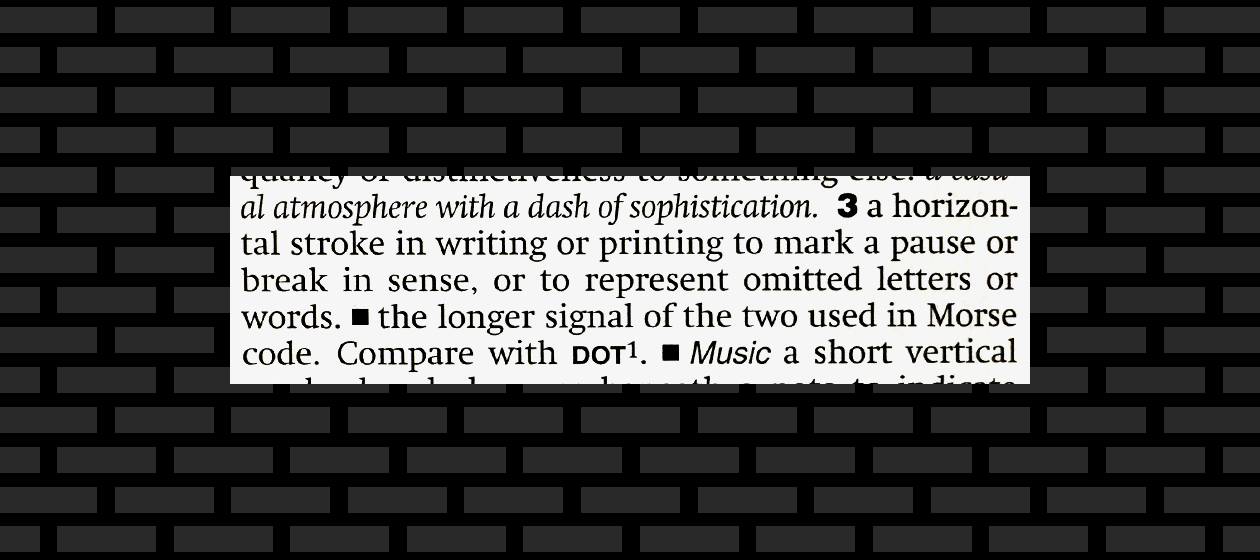

There are other famous cases that make good telling. There's the Unabomber, whose manifesto looked familiar to David Kaczynski, who noted that some phrases, such as "cool-headed logician," were favored by his brother Ted Kaczynski in other writings. Ted, of course, turned out to be the culprit. There's the anonymously-authored book Primary Colors, about Bill Clinton's campaign, whose author was identified as columnist Joe Klein by a professor of English at Vassar College named Don Foster. Foster's name pops up often in discussions of forensic linguistics. He identified Klein on the basis of stylistic quirks, such as his liking for words ending in –ish (e.g., wonkish) and certain coinages (such as "unironic" and "tarmac-hopping"). And: a love of colons. More recently, tweets sent by President Trump have been scrutinized and identified as not having been written by him, thanks to peculiar word choices or punctuation (notably, use of en-dashes).

In the 1930s, the man who kidnapped famous American aviator Charles Lindbergh's son was profiled from the language he used in ransom notes. Authorities were fairly confident the kidnapper was of German origin, given his use of sentences such as, "We warn you for making anyding public or for notify the Polise the child is in gut care."

These examples make great stories, and it's tempting to put on your detective hat and scan a piece of writing for tantalizing clues. In real life, though, someone's identity can't hinge on a single verbal fingerprint or shred of linguistic DNA. Pigott was already on the witness stand and had been impugned by other evidence. Kaczynski was revealed to be the Unabomber by a large accumulation of circumstantial evidence, of which his writing style (and not just a phrase or two) was telling, but was not the only part, or even the first clue. Several people before Foster had already pointed to Klein as the author of Primary Colors, and he was conclusively identified — and forced to admit his authorship — by the presence of his handwriting on an early manuscript of the book.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That's not to say that writing style isn't noteworthy. Indeed, it can matter quite a bit. Malcom Coulthard, an emeritus professor or forensic linguistics at Aston University, has made using language to create reasonable doubt an important part of his career. He has written about a number of cases where people were wrongly convicted of murders thanks to coerced or fabricated confessions. One famous case was that of Derek Bentley, who was convicted of murder in the 1952 shooting of a police officer by his friend while Bentley was already under arrest. A 1991 movie about the case took for its title something he supposedly said to his friend: Let Him Have It, Chris. His conviction was strongly supported by a statement he supposedly gave to police. But analysis of the statement shows that it has some features that are uncommon in ordinary speech — especially for a youth like Bentley — but are typical of the way police officers speak, putting then after the subject, for example, as in: "I then caught a bus" and "Chris then jumped over," rather than before it ("Then I caught a bus"; "Then Chris jumped over"). On the basis of this and other evidence, the conviction was overturned — in 1998, 45 years after Bentley had been executed.

But as a rule, the way you write is much more fluid and changing and probabilistic than your DNA, which never changes. We write in different ways at different times and in different contexts, and the amount of text investigators have to work with is often nowhere near enough for a detailed statistical analysis, and certainly not enough to show something beyond a reasonable doubt. We're getting better at sniffing out anonymous authors, but we still have a long way to go.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.

-

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accents

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accentsThe Explainer The curious case of foreign accent syndrome