10 signature foods with borrowed names

Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When I have Japanese food, I like to have tempura — such a classic! If I have Indian food, I go straight to the vindaloo. And when I go to a Moroccan restaurant, I'm guaranteed to get a tajine.

These are signature dishes, and they have something else in common, too: Their names — and to some extent the foods themselves — are originally from other languages and cultures. (In fact, a lot of international exploration happened because of food. You've heard of the spice trade, right?) Here are 10 signature foods with names that aren't from the culture that made them famous.

1. Tempura

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Tempura is food that has been battered and deep-fried: shrimp, sweet potatoes, eggplant, mushrooms, and more. It's a Japanese classic. There are restaurants all over Japan that specialize in tempura. But the idea — and the word — came from Portuguese missionaries. During the Ember Days, special days of fasting in the Roman Catholic calendar, they would deep-fry fish and vegetables (if you have to ask why, you must be immune to the pleasures of deep-fried foods). The Ember Days are, in Portuguese, têmporas, and it seems that that's where tempura came from, though some people believe the real source is the Portuguese tempero, meaning "seasoning."

2. Ikura

Tempura isn't your favorite? How about sushi and sashimi? Most of the fish have names that are entirely Japanese, but pause to have some salmon roe — ikura — and as those orange beads pop in your mouth like oversized caviar, reflect on how caviar is Russian. Well, the word caviar isn't; it's Turkish, probably ultimately from Persian. The Russian word for caviar is икра, which in our alphabet is ikra. Japanese doesn't allow k and r next to each other like that, so a barely-said u is inserted as an all-purpose filler vowel to make it ikura.

3. Tonkatsu

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Don't like raw fish? How about a nice cooked cutlet of pork (tonkatsu), chicken (torikatsu), or beef (gyukatsu)? The words for "pork," "chicken," and "beef" are of Japanese origin, to be sure. But the katsu part of the word, meaning "cutlet"? It's literally a Japanese version of cutlet. Take the English word cutlet, change the l to r (because there's no "l" in Japanese) and add u to keep consonants from fighting. Then, because the u turns "t" into "ts" (sort of like how we don't say the t in motion as "t"), you get katsuretsu. Cut that down and it's katsu. But, just so you know, English doesn't get final credit for cutlet — and the word doesn't originally have anything to do with cutting, either. It's what we did with the French word côtelette, which literally means "little side."

4. Vindaloo

You'll probably agree that a spicy Indian dish of meat in sauce has little in common with Japanese cuisine. But when you order vindaloo, guess what? Like tempura, it traces to Portugal. Vindaloo isn't too much like Portuguese food, but it got its start in Goa — a part of India with a strong Portuguese influence — with carne de vinha d'alhos ("meat with wine and garlic"). Indian cooks swapped in vinegar for the wine, adjusted the seasoning quite a bit, and turned vinha d'alhos into vindaloo. They dropped the carne, but not the meat, which made it popular with the British, who weren't so keen on the vegetarian diet common in much of India.

5. Congee

Go a little farther south from Goa, down to southern India and Sri Lanka, and you get the Tamil culture. A signature Tamil dish is kanji, a rice porridge. That name really is Tamil. But if you've gone to a Chinese restaurant, you've probably seen congee on the menu there. Many people think of congee as a Chinese specialty, although the dish is popular in various versions with many different names throughout South and East Asia. We call it congee in English because we got the word from canja, which came from the Tamil by way of ... yes, Portuguese.

6. Mandarin

How far can Portuguese go in East Asia? Well, what's the most Chinese thing you can even get? How about mandarin, the name for a scholar class, the official standard form of the language, and, of course, those little oranges? (Or, depending on where you live, a chain of Chinese buffet restaurants?) Well, mandarin is not what any of those are called in Chinese, so it's not fair to say Chinese borrowed the word for them. But the English word mandarin? We got it from Portuguese: mandarim. But wait! Portuguese got it from Malay menteri, which got it from the Sanskrit word mantrin, meaning "counsellor." This word has zig-zagged across the map like those airplane route lines in an Indiana Jones movie.

7. Pizza

Italy got pasta from China, as is widely known, but the names for the many different kinds of pasta are reliably Italian, from linguine ("little tongues") to farfalle ("butterflies" and "bow ties" — same word). But how about that other signature Italian food, pizza? It doesn't come from Portugal, don't worry, and not from China either. No, it comes from Greece. Have you ever noticed how similar pizza and pita are, both as words and as round flat bread items? We don't know for sure — pizza has been a thing in Italy for more than a thousand years — but the odds are pretty good that pizza and pita both come from an older Greek word.

8. Tajine

If you've never had tajine, you have to go see what you've been missing. This delicious stew-like dish from North Africa is named after the conical ceramic dish in which it's cooked. The name for it, like the food and the whole culture, has a distinct Arabic flavor: Moroccan Arabic tažin, from Arabic tājun, from Greek τάγηνον (tágénon). Of course, English is loaded with words from Greek, too! Even butter comes ultimately from Greek — βούτυρον — and so, of course, do olive and oil (our word oil traces back to Greek for "olive oil": ἔλαιον). And a lot of other words have Greek influences way back in history, too; For instance, têmporas, source of tempura, might trace back to τέμνω, though that has nothing to do with delicious deep-fried food.

9. Tzatziki

We know pita is Greek. So is phyllo and that lovely spanakopita you make with it. What else is super Greek? How about tzatziki, that classic garlic yogurt sauce? You know where I'm going with this: The Greek word tzatziki, τζατζίκι, comes from ... Turkish. Its source is cacık (Turkish c sounds like English j). Oh, and as a bonus, moussaka — how can you even get more Greek than moussaka? — also comes from Turkish (musakka), but that in turn comes from the Arabic musaqqa.

10. Barbecue

The secret is out: People borrow food from all over because delicious! And people borrow names for food because they're delicious, too (seriously, we do love new zesty words).

Think about how many food words we use on a daily basis that are obvious borrowings from other languages. Of course, we mostly recognize those foods as being from those countries, not ours. And where an American classic has a name from another country, it can be really obvious, like hamburger (from Hamburg) or turkey (read this). Even where it's not obvious, we can't be too surprised, given that English steals from everywhere: Chowder, for instance, comes from French chaudière, or "pot" (also related to cauldron by way of Latin).

The classic American dish barbecue is no exception. We didn't get the name from the Bar-B-Q Ranch; we got it from Spanish barbacoa, which in turn came from barbakoa in Taíno, a Caribbean language. But since barbecue's also popular in the West Indies, it's not completely fair to say barbecue isn't from where it's from — it's just that some of us have forgotten where we got it.

Well, relax. Have something that everyone knows was invented in America. How about some Buffalo wings? It's widely agreed that they got their start at the Anchor Bar in Buffalo. And it's just random chance that the name of that city is a word we got from Portuguese búfalo, which traces back through Latin to Greek βούβαλος ...

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

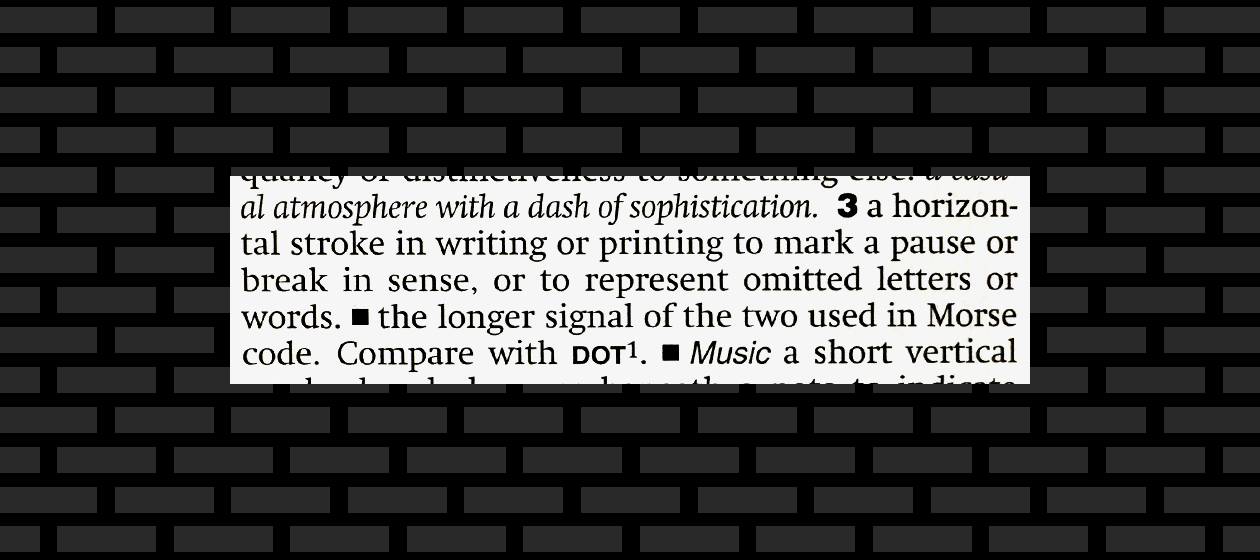

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.

-

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accents

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accentsThe Explainer The curious case of foreign accent syndrome