There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In Paris to mark the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War I this past Saturday, President Trump was, by his standards, in a pensive mood. "Is there anything better to celebrate," he tweeted, "than the end of a war, in particular that one, which was one of the bloodiest and worst of all time?"

I read the post and thought little of it, aside from noting its relative propriety. From an account that dabbles in "horseface" and "Rocket Man," enthusiasm for peace, even awkwardly phrased, is a welcome change. But my response was apparently not universal. The benign tweet was soon ginning up controversy, with Twitter raging into debate over whether "celebrate" should have been replaced with the more solemn "commemorate." Days later, the argument appears to have life in it yet.

This is an acutely stupid feud. "Commemorate" may have been better, sure, but it is entirely good and right to celebrate the end of a war! They certainly celebrated in 1918. There are reasons abundant to be angry at the president, but his word choice here isn't one of them. Why are we fighting about it?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Perhaps it is because we are addicted to fighting, and any excuse will do. I recently learned of a German word, streitsüchtig, which is typically translated "quarrelsome." But its literal meaning is dispute-addicted. It describes not just a tendency toward conflict but a certain hunger for it — a need for discord or yearning for something to oppose.

Streitsüchtig describes our politics perfectly. We are addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse. The addiction is not endemic to any one spot on the political spectrum, nor is it confined to unreasonable reactions to Trump's more reasonable moments. And as long as it remains, I struggle to see a scenario in which we return to any semblance of the political normalcy many say they desire.

What makes our streitsüchtig state so insidious is it really does have biological similarities to addiction. When politics gets a rise out of us, it triggers the same fight or flight response real danger can engender. Our bodies experience the same heightened levels of the hormone cortisol. And when we feel we've won an argument, our brain self-rewards with more hormones, adrenaline, and dopamine. They create "a feeling any of us would want to replicate," writes Judith E. Glaser at Harvard Business Review. "So the next time we're in a tense situation, we fight again. We get addicted to being right."

Once we start fighting about politics, the chance of "winning" makes us want to fight more. And chronically high cortisol secretion from chronic arguing comes with side effects including anxiety and difficulty learning and remembering information. So the more we argue, the more we want to argue, and the less capable we are of arguing well. "The more dopamine and cortisol, the more we lose our ability to discern truth from post-truth, the more irritable we become, and the more we abandon our cognitive control and with little regard for the consequences," explains Robert H. Lustig, an emeritus professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of California San Francisco.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Our streitsüchtig problem is self-perpetuating, and our brains are working against us.

As much as it has become cliché to rag on social media as an exacerbator of our political problems, the charge here is fair. Before 2005 or so, the average American simply did not have the same opportunity to exercise a fighting addiction. On any given day, you'd encounter the same 30 or 40 people — family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, or classmates — with whom you would not regularly descend into real political vitriol. Practical necessity, if not politeness, prevents it.

Those inhibitions are gone when squabbling with someone whom you've never met in the comments section of a mutual friend's Facebook post, and the way this personal political turmoil is now perpetually available to us is legitimately a new thing. Even if, like me, you've sworn off Facebook arguments for good, the act of encountering other people's disputes may be enough to activate your streitsüchtig brain.

Our streitsüchtig habits are on display in political trolling of all sorts, in trying to "own the libs" or frustrate political opponents for frustration's sake. A better-known German word, schadenfreude, is in play in our fighting addiction, too. Feeling gratified when your political enemy suffers is a symptom of fighting addiction, the darker side of feeling happy when your allies succeed. Fighting addiction is evident in the way a majority in both parties say it's "stressful to talk about politics with people who differ on Trump" — and then keep talking anyway.

I'm not sure how to break a national case of fighting addiction. But if it's not broken, how can we ever have a "normal" president or political discourse again?

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’

Anthropic: AI triggers the ‘SaaSpocalypse’Feature A grim reaper for software services?

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

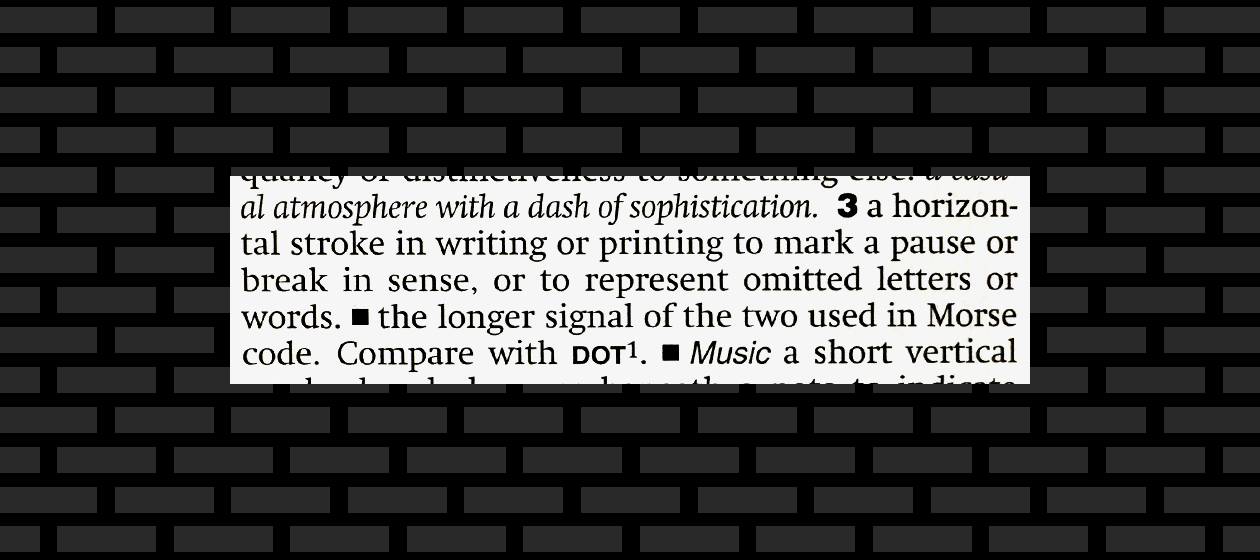

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guideThe Explainer Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.

-

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accents

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accentsThe Explainer The curious case of foreign accent syndrome