Dashes and hyphens: A comprehensive guide

Everything you wanted to know about dashes but were afraid to ask

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Many people don't know there are different kinds of dashes. They often call a hyphen a dash — which, to an editor, is like calling a period a colon.

In fact, there are an unnerving assortment of horizontal lines available to typographers, including (but not limited to) the hyphen, soft hyphen, minus sign, angled dash, swung dash, en dash, figure dash, em dash, two-em dash, three-em dash, and horizontal rule.

Here's a brief rundown:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Hyphen: -

A hyphen is that little bit of mortar between the bricks of compound words such as Coca-Cola and high-strung. Its origins trace back to ancient Greece; its modern form dates to the 1400s. Gutenberg, the inventor of moveable type, is credited with first using it to let a word break off at the end of one line and pick up on the next. It's the only one that's standard on typewriter keyboards, so people tend to use it to stand in for… well, all the other ones.

The ancients among us who learned to type on actual typewriters were taught to use two hyphens to make a dash, and many people still do — but, like underlining for italics and double spaces after periods, that was only meant as an indication for the typesetter. Printed matter using proper full fonts is supposed to use the right lines in the right places. Microsoft Word has decided to be helpful in this: By default, if you type two dashes between two words, they become an em dash — unless you put a space on either side, in which case they become an en dash, same as if you just type space-hyphen-space.

Soft hyphen: -

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is a creature of the computer age: It's a hyphen you can insert in a word to tell it to break at that place and no other, and it only shows up if the word breaks at the end of a line. Otherwise it's invisible.

Non-breaking hyphen: ‑

This is the opposite of a soft hyphen: You always see it and it does not allow a line break right before or after it.

Minus sign: −

This is used in math, of course. Why not just use a hyphen or an en dash? They (usually) don't look the same, but the difference is not huge. And in Excel, a hyphen functions as a minus sign (an en dash does not!). But if you're working with a book or article that has a lot of math in it, it can be very useful to be able to find all the minus signs and only the minus signs.

Angled dash: ¬

Have you seen this thing? Sometimes if you view hidden characters in a document it will stand in for something else, but when it's being itself it's not. I mean it's "not." As in symbolic logic. See the next one …

Swung dash: ~

This looks just like a tilde (as in piñata), but in it's in the middle of the line. Some people use it as a fancy dash, but its official use is to mean "approximately," as in "I'll be there at ~1:00." It has also been used in formal logic to mean "not" (which, frankly, "I'll be there at ~1:00" often really means), but now the angled dash is preferred for that.

En-dash: –

Now we're into the real dashes. An en dash is supposed to be half the width of an em dash, but some fonts make it long and some make it quite short (in which case they may make it a little thinner and higher than a hyphen). You can use it to indicate number ranges: "The library is open 10:00–5:00." You can use it in some other places you would use to: "The Washington–Moscow hotline." Professional editors, on the advice of such guides as The Chicago Manual of Style, use an en dash in place of a hyphen when making a compound with something that's already a compound, e.g., "New York–based" or "Coca-Cola–drinking." In fact, this is one way you can tell a professional editor or typographer has been let loose on a text, because no one else ever does this.

You can also use an en dash with a space on either side in place of an em dash. This is common in England and is also accepted in North America. Robert Bringhurst, in The Elements of Typographic Style, recommends it because the em dash is too long and "belongs to the padded and corseted aesthetic of Victorian typography." An added advantage of doing this is that all browsers and applications can make a line break next to it, which is not true with an em dash with no spaces next to it.

Figure dash: ‒

Can you see the difference between this and an en dash? In many type faces there is none. It's a dash that is as wide as a standard numeral and is meant to be used in such things as phone numbers (867‒5309). Some typographers will use them in place of en dashes in contexts and fonts where they think they look better. They will smile to themselves and sigh happily. No one else will take notice.

Em-dash: —

The em dash is meant to be as long as the full height of the font — not that it always is. The em dash is the archetype of the dash. It's the all-purpose punctuation that can be swapped in place of a comma, a colon, a semicolon, parentheses, or whatnot — but if you use too many of them, your reader will end up breathless from all that dashing around. And there are rules, to be sure. Pay an editor to know them for you.

Actually, the rules are still evolving. A century or so ago it was common and accepted to put a colons or semicolons after a dash; now it's forbidden. Even if you're using them in place of parentheses and would normally put a comma after — like this —, by the rules of Chicago (and others) you must ditch the comma.

Also supposedly forbidden is putting a space on either side of an em dash; if you want to use spaces, according to those who pronounce on such things, use an en dash (which is why MS Word converts -- to – between spaces). But some publications ignore this counsel, as is their right — The Week, for one.

The em dash can also be used to indicate when someone has been cut off, as well as to attribute speech to someone (as at the end of a quotation) and, in some European texts, in place of quotation marks to indicate when someone is speaking. So in theory you could get something like this:

—They couldn't hit an elephant at this dist—

—John Sedgwick (last words)

Two-em dash: ——

This dash is as long as two em dashes (duh). If your font doesn't have it, just use two em dashes. It's for when you're blanking out someone's name or another word, as in "So D—— T—— said 'I did try to —— her.'"

When you put all the dashes and their fussy rules together, you can get something fun like this:

—I saw that Coca-Cola–drinking son-of-a— Oh, —— it, what's his name—his number is 867‒5309—I saw him on the Washington–New York high-speed train.

Three-em dash: ———

Obviously, this is three em dashes glued together. This is used in bibliographies when you've already named the author once and you want to indicate that it's the same person:

Einstein, Albert. Some Stuff I Wrote.

———. Some More Stuff.

James Harbeck is a professional word taster and sentence sommelier (an editor trained in linguistics). He is the author of the blog Sesquiotica and the book Songs of Love and Grammar.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?

In the future, will the English language be full of accented characters?The Explainer They may look funny, but they're probably here to stay

-

10 signature foods with borrowed names

10 signature foods with borrowed namesThe Explainer Tempura, tajine, tzatziki, and other dishes whose names aren't from the cultures that made them famous

-

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged culture

There's a perfect German word for America's perpetually enraged cultureThe Explainer We've become addicted to conflict, and it's only getting worse

-

The death of sacred speech

The death of sacred speechThe Explainer Sacred words and moral terms are vanishing in the English-speaking world. Here’s why it matters.

-

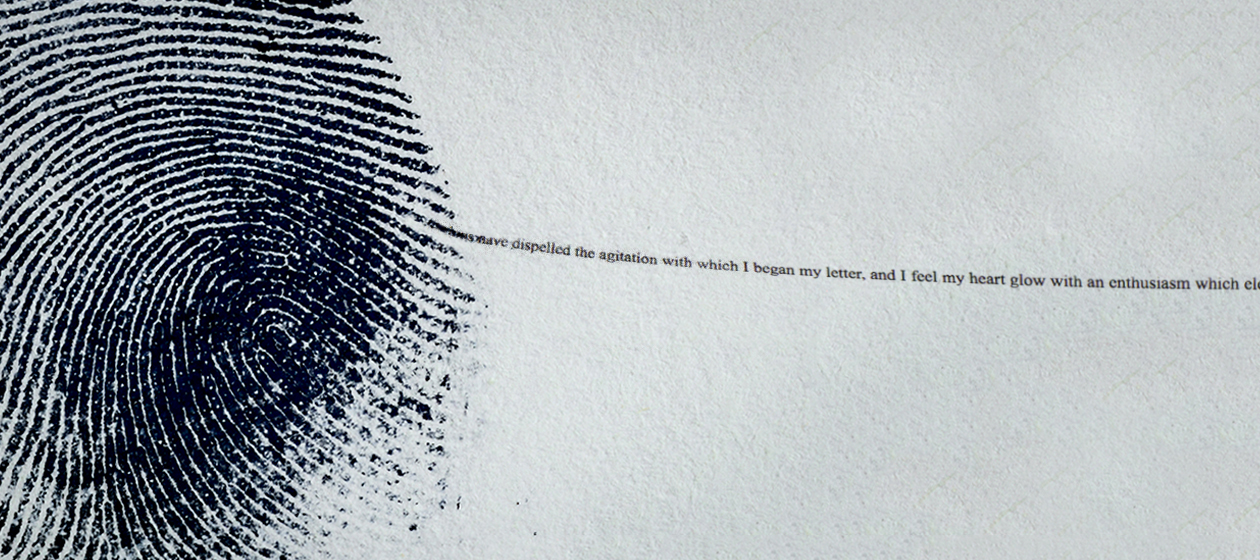

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous author

The delicate art of using linguistics to identify an anonymous authorThe Explainer The words we choose — and how we use them — can be powerful clues

-

A brief history of Canadian-American relations

A brief history of Canadian-American relationsThe Explainer President Trump has opened a rift with one of America's closest allies. But things have been worse.

-

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOn

The new rules of CaPiTaLiZaTiOnThe Explainer The rules for capitalizing letters are totally arbitrary. So I wrote new rules.

-

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accents

The curious case of people who can't stop speaking in foreign accentsThe Explainer The curious case of foreign accent syndrome