California's open primaries: A solution to partisan gridlock?

Californians are testing a new primary system, hoping the switch from party-based primaries will benefit more moderate politicians

On Tuesday, all eyes are on Wisconsin, where Gov. Scott Walker (R) is hoping to avoid a recall in a contentious battle that has divided Wisconsinites along starkly partisan lines. But California's election day, though less covered by the media, may have similarly important repercussions for the future of American politics. California for the first time is holding open primaries for its state and federal races in November, instead of allowing Democrats and Republicans to continue their tradition of fielding separate primaries. The change was approved by voters in a 2010 referendum in a bid to reduce partisan gridlock, particularly in the state's notoriously dysfunctional state legislature. Here, a guide to California's open primary system:

How do open primaries work?

Politicians of any party will be allowed to contend in free-for-all primaries for California's state and congressional races. The idea is that the top two vote-getters will face each other in the general election, even if they're both Democrats or both Republicans.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How will that reduce partisanship?

Under the traditional primary system, Republicans and Democrats tend to elect candidates who appeal to their respective bases. As a result, state legislatures and Congress are filled with candidates who hold more extreme positions. (The situation was especially bad in California, where incumbent parties almost always won, leaving its political rank-and-file virtually unchanged for decades.) An open primary, on the other hand, theoretically encourages all candidates to appeal to as wide a swath of voters as possible, which in turn encourages moderate stances on issues.

How has the open primary changed voting in California?

In combination with a statewide redistricting effort, the new system has shaken up the state's normally predictable primaries. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D), for example, is in a primary race featuring no less than 23 opponents, though the popular incumbent is still expected to win. House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D) is facing 13 rivals. Meanwhile, due to redistricting, it's predicted that Democratic Reps. Howard Berman and Brad Sherman will face off against each other in the fall.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Will the new system favor one party over another?

Analysts say that Democrats, with their numerical superiority in the state, have the most to gain from the new system. Democrats expect to pick up four to five House seats in the fall, and Pelosi has even gone so far as to proclaim that the way to a Democratic majority in the House "runs through California."

Will open primaries really reduce partisanship?

Maybe, though some analysts have cast doubt on the theory, saying it's "unclear if candidates positioning themselves as moderates will actually seek more moderate policies" once in office, say Justin Scheck and Vauhini Vara at The Wall Street Journal. The candidates are, at the very least, "touting their moderate credentials." However, even an open primary might not fix gridlock in California, where the legislature needs a two-thirds supermajority to pass any tax increases that might lower the budget deficit.

Sources: Associated Press, Atlanta Journal Constitution, CBS News, The Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal

Read more political coverage at The Week's 2012 Election Center.

-

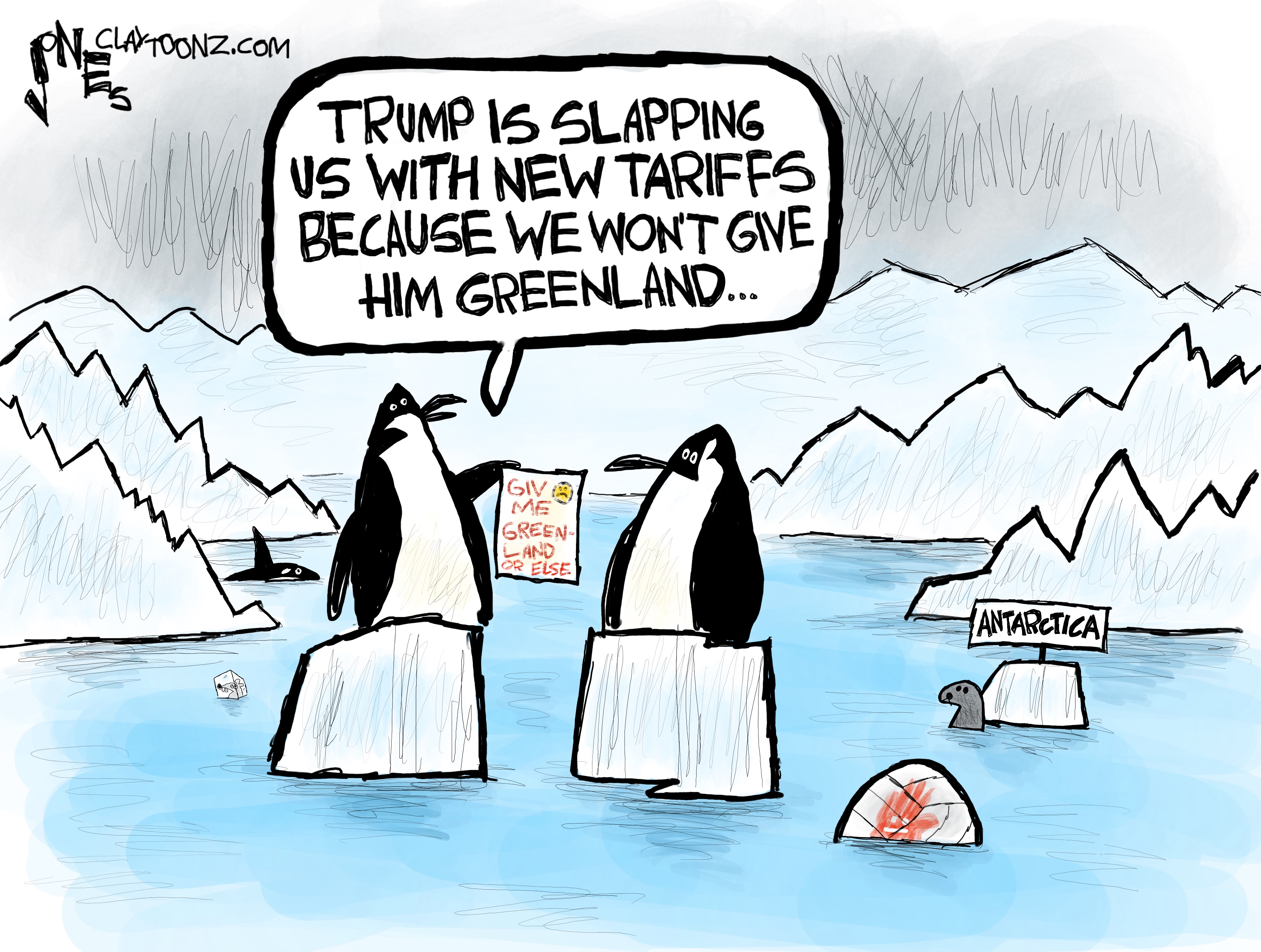

Political cartoons for January 19

Political cartoons for January 19Cartoons Monday's political cartoons include Greenland tariffs, fighting the Fed, and more

-

Spain’s deadly high-speed train crash

Spain’s deadly high-speed train crashThe Explainer The country experienced its worst rail accident since 2013, with the death toll of 39 ‘not yet final’

-

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?

Can Starmer continue to walk the Trump tightrope?Today's Big Question PM condemns US tariff threat but is less confrontational than some European allies

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred