The electric motor made from a single molecule

The world's tiniest electric motor is thousands of times smaller than a strand of human hair — and could revolutionize engineering and medicine

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

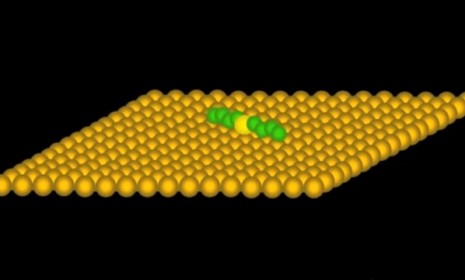

The Guinness World Records organization has yet to officially weigh in, but it appears that chemists at Tufts University have created the world's smallest electrical motor. Thousands of times narrower than a strand of hair, the motor is the size of a single molecule — and could transform medicine and engineering. What's the story behind this breakthrough? Here, a brief guide:

Why build such a tiny motor?

In addition to "forming a part of the tiniest machines the world has ever seen," says Jason Palmer at BBC News, the motor could be used in medicine to control the delivery of drugs to targeted spots in the body. Engineers could use it to generate microwave radiation or build nano-sized electromechanical systems. Motors this small have been developed before, but had to be driven by light or by chemical reactions. The big breakthrough here is that, powered by electricity, a single molecule can be manipulated in a more precise way than ever before.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How small is it?

The Guinness Book of World Records has yet to confirm, but this should qualify as the smallest electrical motor ever, says Katie Scott at Wired. The device is one nanometer across — that's 60,000 times smaller than a strand of human hair. To compare, the tiniest motor on record up to now is 200 nanometers across.

How did they build this?

Scientists used the metal tip of a special "low temperature scanning microscope" — there are only 100 in the U.S. — to apply an electrical charge to a special type of sulfide molecule. It has carbon and hydrogen atoms radiating from it, forming "arms" that, when charged, whip around a single sulphur atom that serves as an axis. The tricky part was finding the best temperature to observe and control the motor — minus 268 degrees Celsius, it turned out. It works at higher temperatures, but spins too fast to control, says Tufts professor E. Charles H. Sykes, the lead researcher, in the International Business Times. "At that speed, it's just a blur."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sources: BBC News, Examiner, International Business Times, Wired