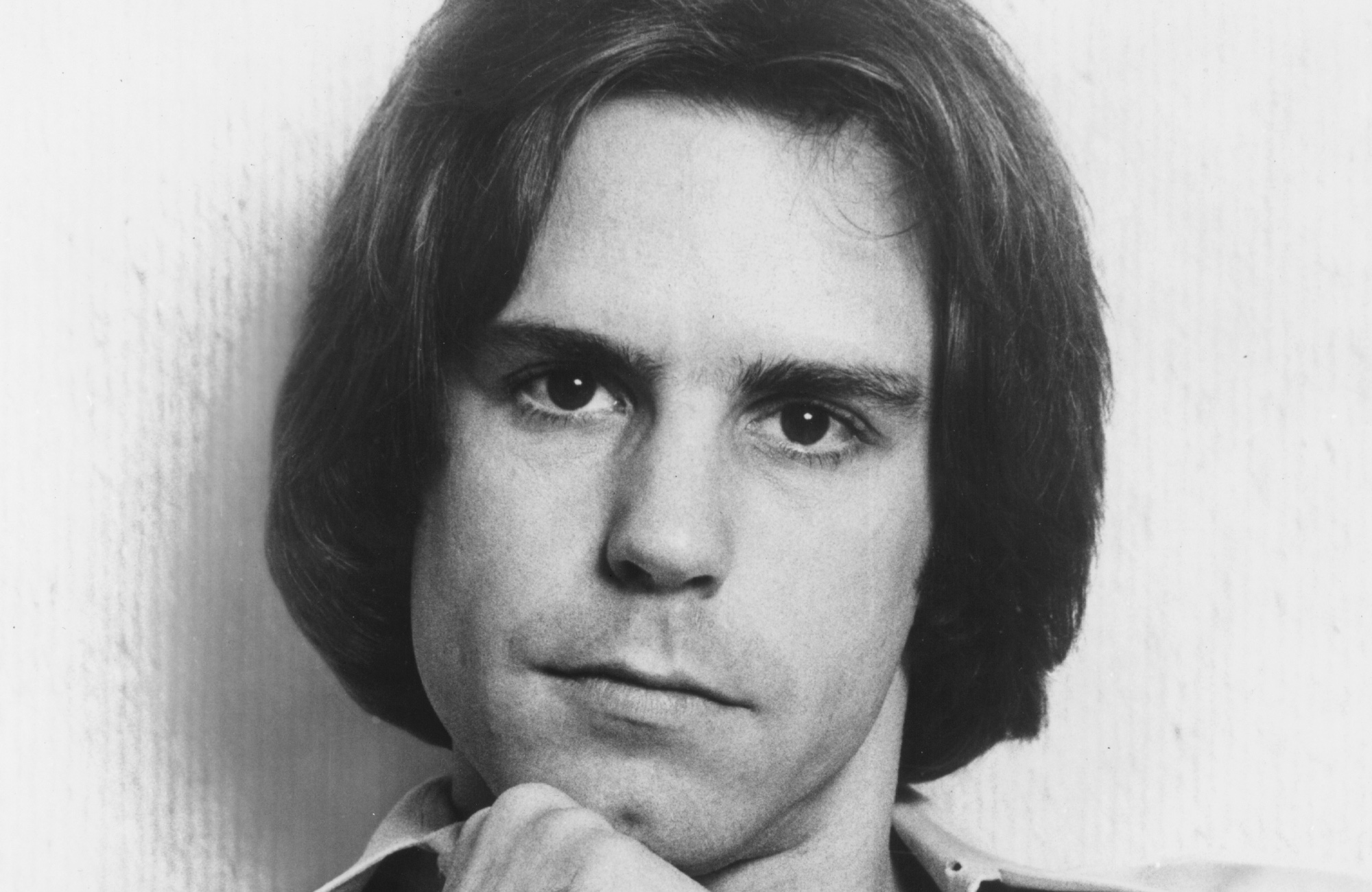

David ‘Honeyboy’ Edwards, 1915–2011

The last of the original Delta bluesmen

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

David “Honeyboy” Edwards rode the rails and played at Mississippi fish fries with iconic bluesman Robert Johnson in the 1930s. “We would walk through the country with our guitars on our shoulders, stop at people’s houses, play a little music, walk on,” he once said. Edwards was on hand when Johnson drank the poisoned whisky that killed him, in 1938, and six decades later, he was still keeping the original Delta blues sound alive.

Edwards was born in Shaw, Miss., as the son of a sharecropper and grandson of a slave, said the Chicago Sun-Times. His father, a guitarist and violinist in “country jukes throughout Mississippi,” bought him a Sears guitar for $4 and taught him how to play. At the age of 14, Edwards left home to hobo with guitarist Big Joe Williams, who helped cultivate the musician’s “distinctive style of uneven phrasing and skewed timing.”

Over the following years, said The New York Times, Edwards played or toured with almost every blues musician “who worked in the idiom.” Big Walter Horton, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson—all were familiar with Edwards’s “coarse, keening vocals” and “slashing bottleneck-style guitar work.” After almost two decades on the road, the bluesman made Chicago his permanent home in the 1950s. He worked on construction sites and in factories by day, and played the blues at night.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Edwards never won the fame or recognition of contemporaries like Muddy Waters or Willie Dixon, said the Chicago Tribune, but the blues revival of the ’60s made him a “desired attraction on stages around the world.” He toured endlessly, introducing the “work songs and hymns of a black underclass” to several generations of fans. He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1996, won a lifetime achievement Grammy in 2010, and was still playing up to 100 shows a year well into his 90s.

For Edwards, the blues always reflected the lives of the Delta musicians who created it. “The verses which are sung in the blues is a true story, what people are doing...what they all went through,” he said. “It’s not just a song, see?”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s Wife

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s WifeIn the Spotlight Trollope found fame with intelligent novels about the dramas and dilemmas of modern women

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

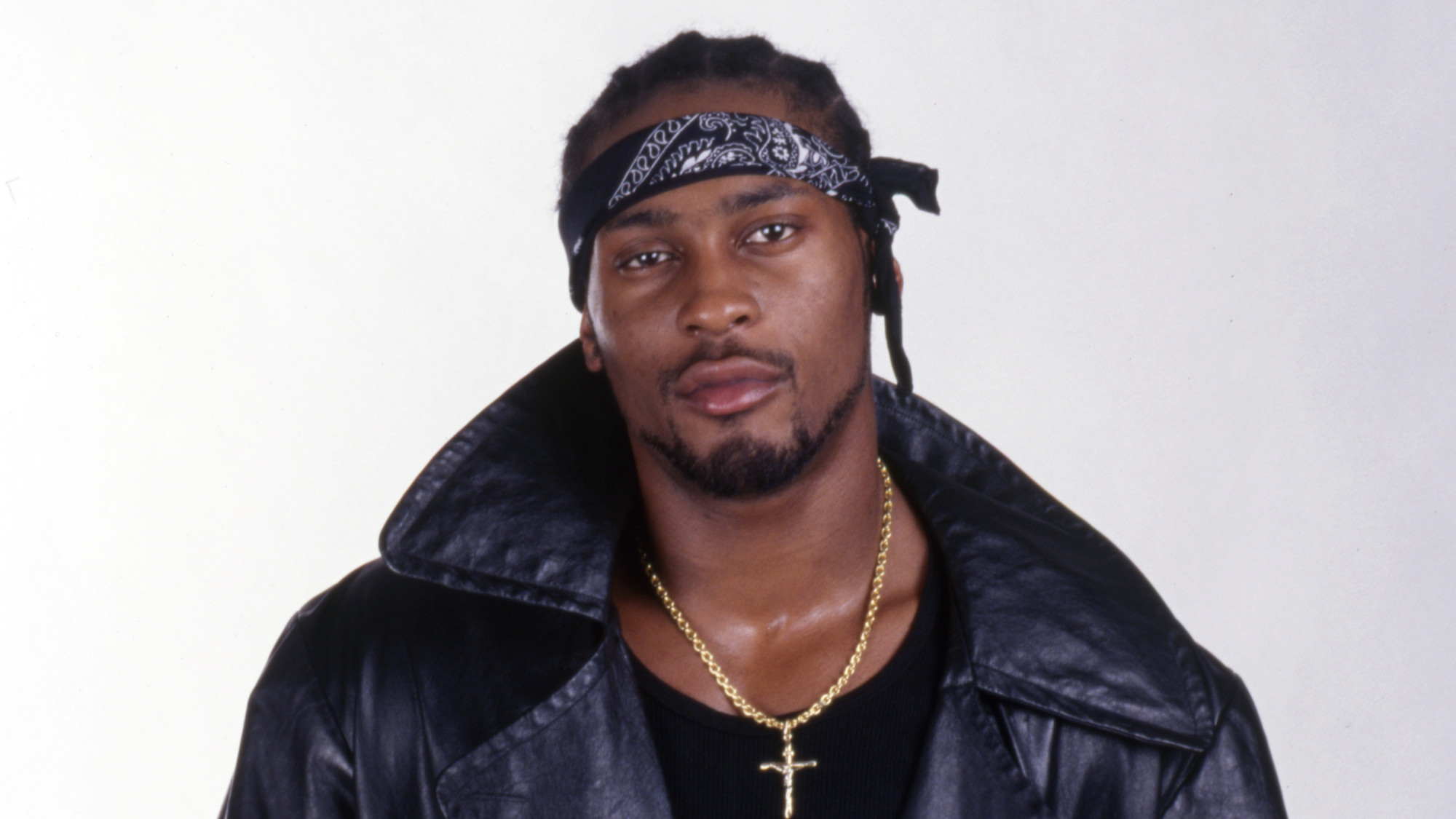

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

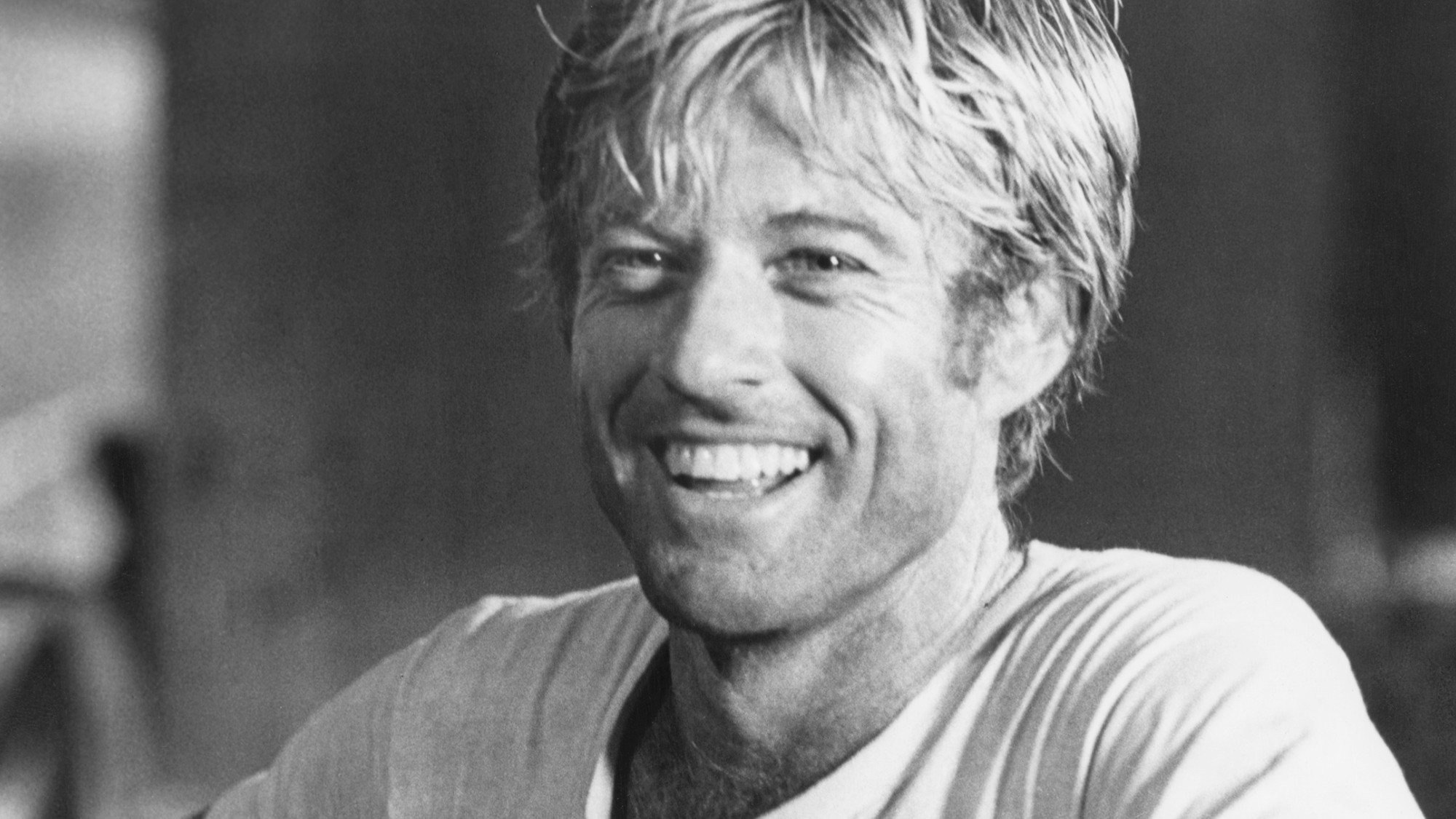

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance