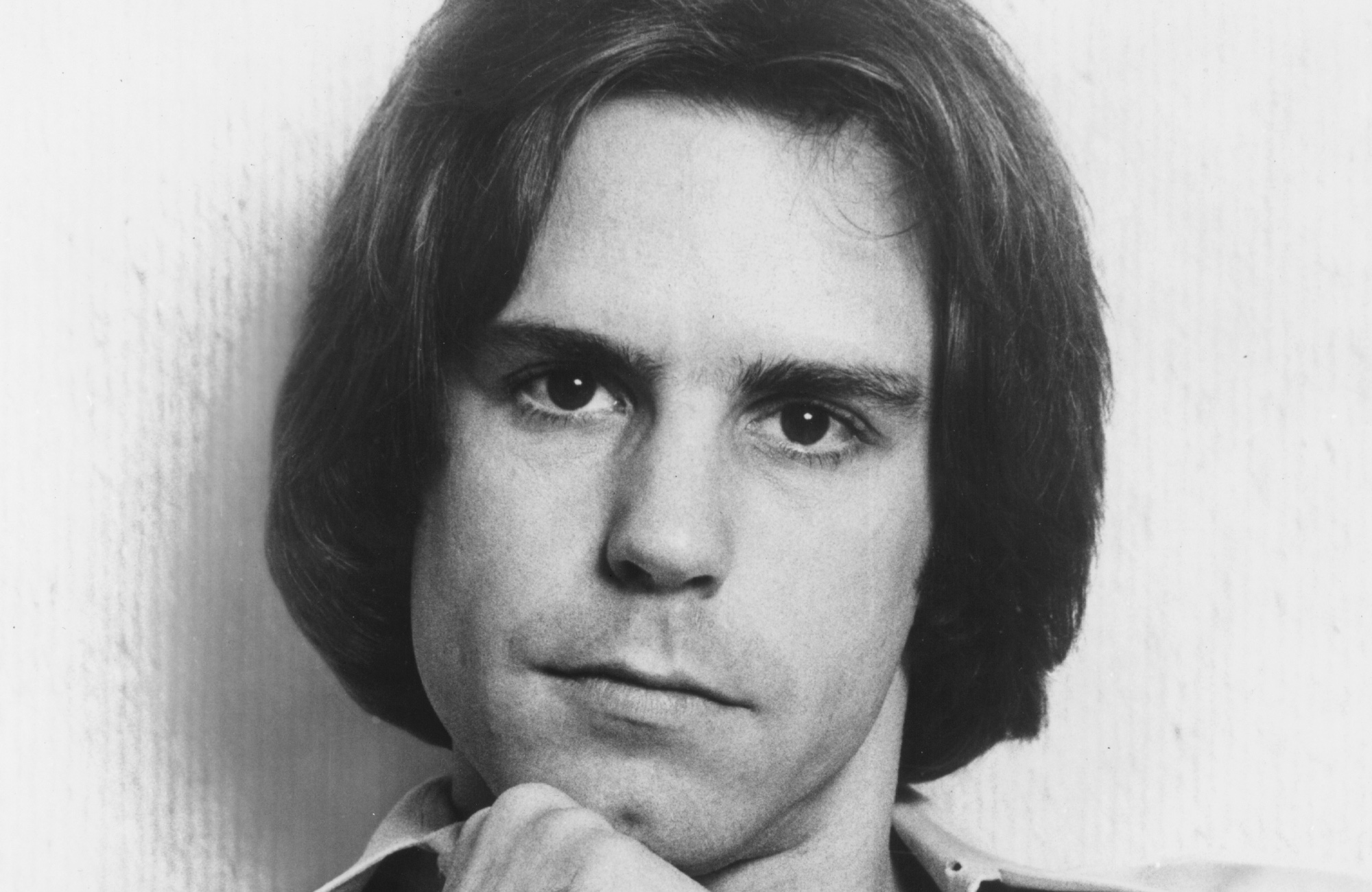

Vitaly Ginzburg

The Soviet physicist who worked on the H-bomb

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vitaly Ginzburg

1916–2009

Vitaly Ginzburg, who helped develop the Soviet hydrogen bomb, was later a survivor of Stalin’s pogrom against Jewish intellectuals in the 1950s. In 2003, he shared the Nobel Prize for his work on superconductivity.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Born in Moscow in the waning days of czarist Russia, Ginzburg earned two doctorates in physics from Moscow University, in 1940 and 1942, said The Washington Post. He also joined the Communist Party, a decision he later “seemed to regret.” In 1948, he and other physicists at the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow raced to develop a hydrogen bomb before the U.S. “The team had little idea how to proceed.” Andrei Sakharov proposed using layers of uranium as fuel, while Ginzburg suggested lithium-6. Their combined efforts eventually succeeded in creating the H-bomb.

In the 1950s Stalin “initiated a wave of anti-Semitism and hostility toward intellectuals,” said The New York Times. Ginzburg was removed from the H-bomb project and accused of being an anti-communist. Adding to his difficulties was his marriage to a woman wrongly accused of involvement in a plot to assassinate the Russian leader. Only his prestige as a scientist, Ginzburg believed, saved him from the firing squad. Soon after Stalin died, the Russians detonated an H-bomb, and Ginzburg was ultimately elected a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Ginzburg eventually turned his attention to the rapidly emerging field of superconductivity, said the Los Angeles Times. Earlier research had yielded few practical results “because even weak magnetic fields interfered with a material’s ability to conduct electricity.” But Ginzburg and another physicist created a series of equations that paved the way for the use of superconductors in such fields as medical imaging. A confirmed atheist, he also became an outspoken opponent of anti-Semitism, a supporter of the state of Israel, and a leading critic of the Kremlin’s growing relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church.

“I am convinced that the bright future of mankind is connected with the progress of science,” he wrote, “and I believe it is inevitable that one day religions will drop in status to no higher than that of astrology.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

The identical twins derailing a French murder trial

The identical twins derailing a French murder trialUnder The Radar Police are unable to tell which suspect’s DNA is on the weapon

-

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek star

James Van Der Beek obituary: fresh-faced Dawson’s Creek starIn The Spotlight Van Der Beek fronted one of the most successful teen dramas of the 90s – but his Dawson fame proved a double-edged sword

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flame

Bob Weir: The Grateful Dead guitarist who kept the hippie flameFeature The fan favorite died at 78

-

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new France

Brigitte Bardot: the bombshell who embodied the new FranceFeature The actress retired from cinema at 39, and later become known for animal rights activism and anti-Muslim bigotry

-

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like water

Frank Gehry: the architect who made buildings flow like waterFeature The revered building master died at the age of 96

-

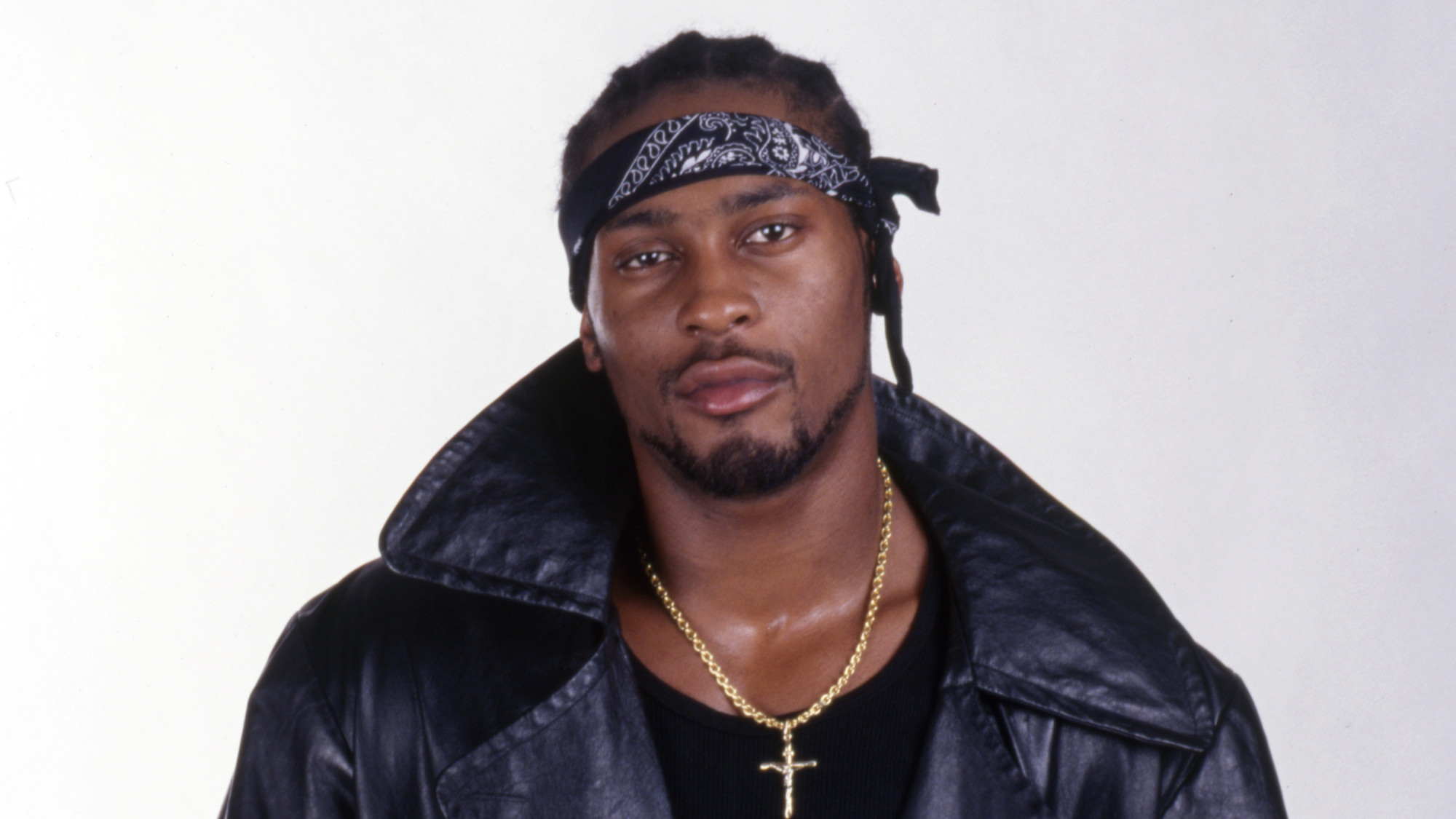

R&B singer D’Angelo

R&B singer D’AngeloFeature A reclusive visionary who transformed the genre

-

Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley

Kiss guitarist Ace FrehleyFeature The rocker who shot fireworks from his guitar

-

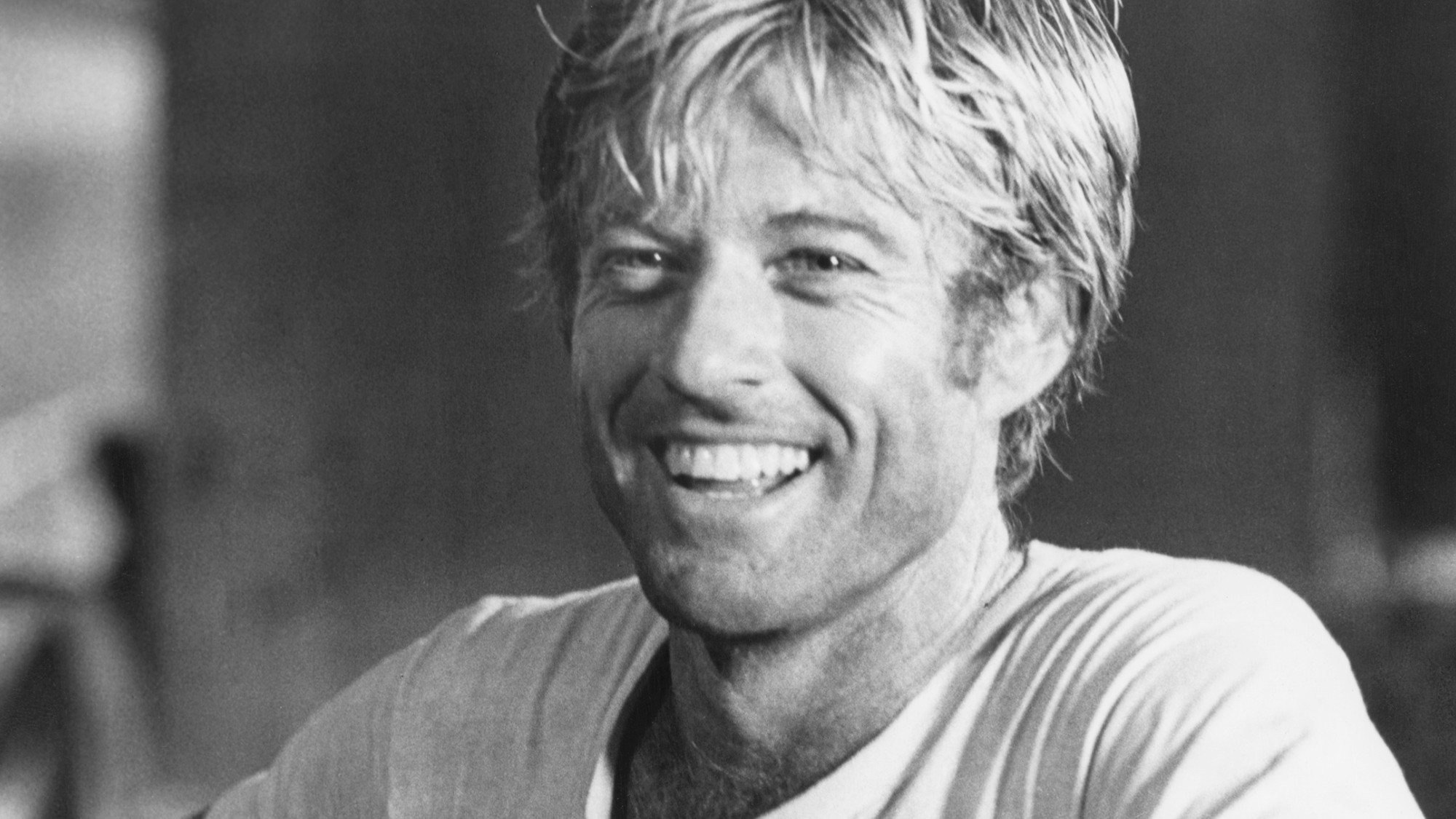

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film Festival

Robert Redford: the Hollywood icon who founded the Sundance Film FestivalFeature Redford’s most lasting influence may have been as the man who ‘invigorated American independent cinema’ through Sundance