Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The Soviet dissident who chronicled the evils of communism

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Soviet dissident who chronicled the evils of communism

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

1918–2008

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who has died at 89, was one of the 20th century’s most resolute and eloquent opponents of the tyranny of the Soviet Union. He won the 1970 Nobel Prize in literature for work that laid bare the totalitarian state’s myriad cruelties, and he was widely seen as the living symbol of a free Russia. Once asked about the secret of his art, Solzhenitsyn replied, “The secret is that when you’ve been pitched headfirst into hell you just write about it.”

Born in the Caucasus a year after the Bolshevik Revolution, Solzhenitsyn was an ardent young communist, said The Boston Globe. A math teacher by training, “he took along a copy of Marx’s Das Kapital on his honeymoon” and joined the Red Army after the 1941 Nazi invasion. But in 1945 he was arrested for his increasingly anti-Stalinist views and sentenced to eight years in labor camps. There, he resolved to oppose what he called communism’s “malevolent and unyielding nature.” His first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, was published in the USSR in 1962 as part of Nikita Khrushchev’s Cold War thaw with the West. Depicting the bleak existence of a good-natured prison camp inmate, it was a major success. “There are three atom bombs in the world,” a friend told Solzhenitsyn at the time. “Kennedy has one, Khrushchev has another, and you have the third.” The government press organ Izvestia even hailed Solzhenitsyn as “a true helper of the Party.”

But “the fall of Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev’s ascent to power in 1964 ended the ‘thaw,’” said the Financial Times. Authorities stopped Solzhenitsyn’s public readings and confiscated his then-unpublished novels The First Circle and The Cancer Ward. Solzhenitsyn responded by keeping a pitchfork near his bed and declaring, “No one can bar the road to truth, and to advance its cause I am prepared to accept even death.” He managed to smuggle out The Gulag Archipelago, his massive dissection of Soviet terror, which former U.S. Ambassador George Kennan called “the greatest and most powerful single indictment of a political regime ever to be leveled in modern times.” In 1974, shortly after its publication in the West, Solzhenitsyn was arrested and thrown out of the country—the first Soviet since Leon Trotsky, in 1929, to be stripped of his citizenship and expelled.

Settling down in rural Vermont, protected by “a fence topped with barbed wire and a closed-circuit television system,” Solzhenitsyn continued to publish and inveigh against the Soviet system, said the Los Angeles Times. In exile, “the bearded author with piercing blue eyes and a diffident manner” was hailed as a champion of human rights. But Solzhenitsyn was a problematic figure. He called détente a “sham,” and “viewed the United States and the West in general as flaccid, morally weak, and cravenly materialistic.” His diatribes “were at times tainted with paranoia, anti-Semitism, and bigotry.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991, seemed the culmination of everything Solzhenitsyn had fought for, said The New York Times. In 1994 he returned to his homeland, which he called “tortured, stunned, altered beyond recognition” due to crime, corruption, and unworthy leaders. After his initial welcome, the response turned “tepid”; many of his fellow countrymen thought “his oratory hollow, his time past, and his mission unclear.” Still, he resettled to a rural estate outside Moscow and, “in the last years of his life, he embraced Vladimir Putin as a restorer of Russia’s greatness.”

“Literature,” Solzhenitsyn declared in his Nobel lecture, “is the living memory of a nation. It sustains within itself and safeguards a nation’s bygone history. But woe to that nation whose literature is cut short by the intrusion of force.”

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

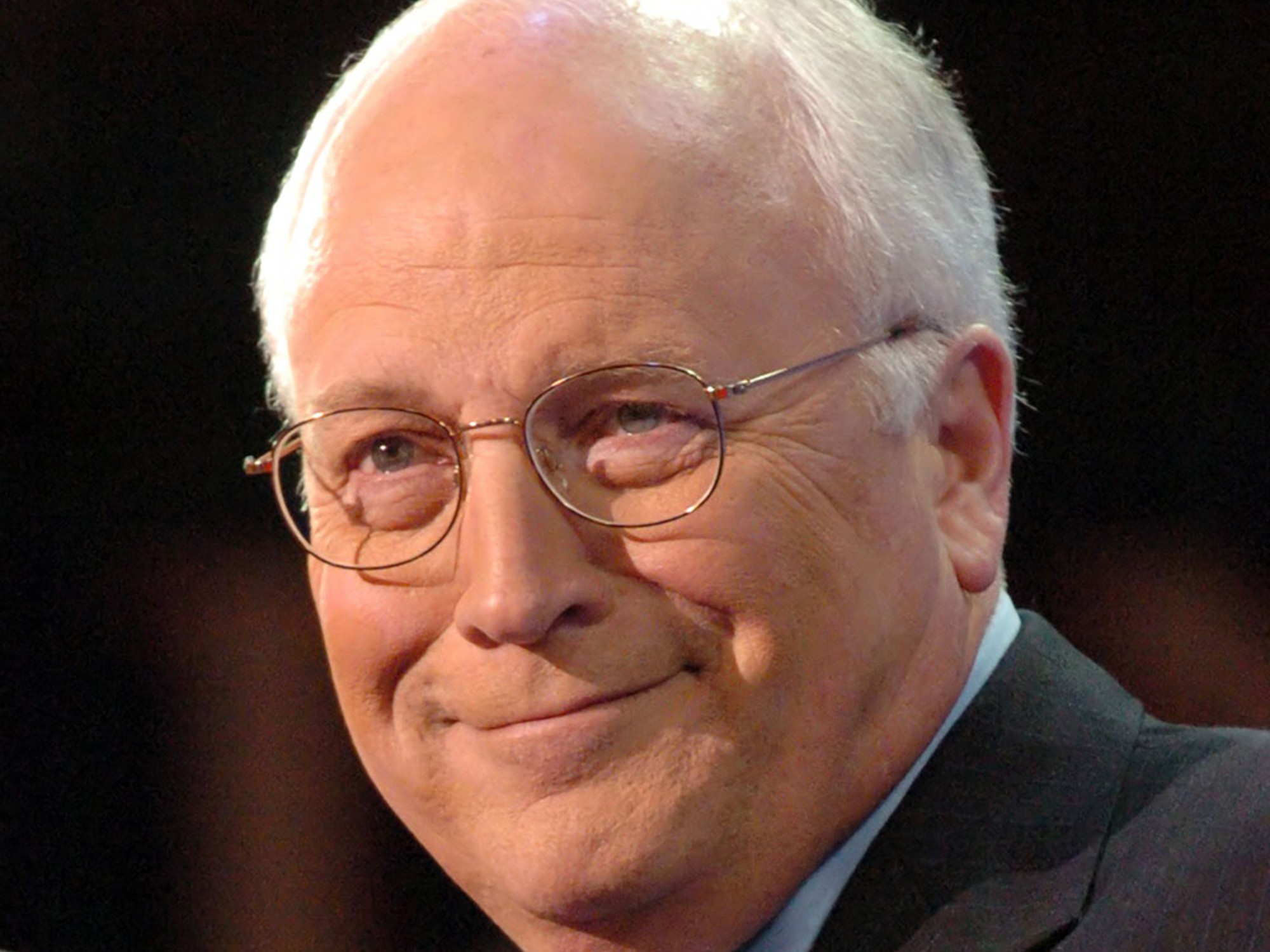

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terror

Dick Cheney: the vice president who led the War on Terrorfeature Cheney died this month at the age of 84

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

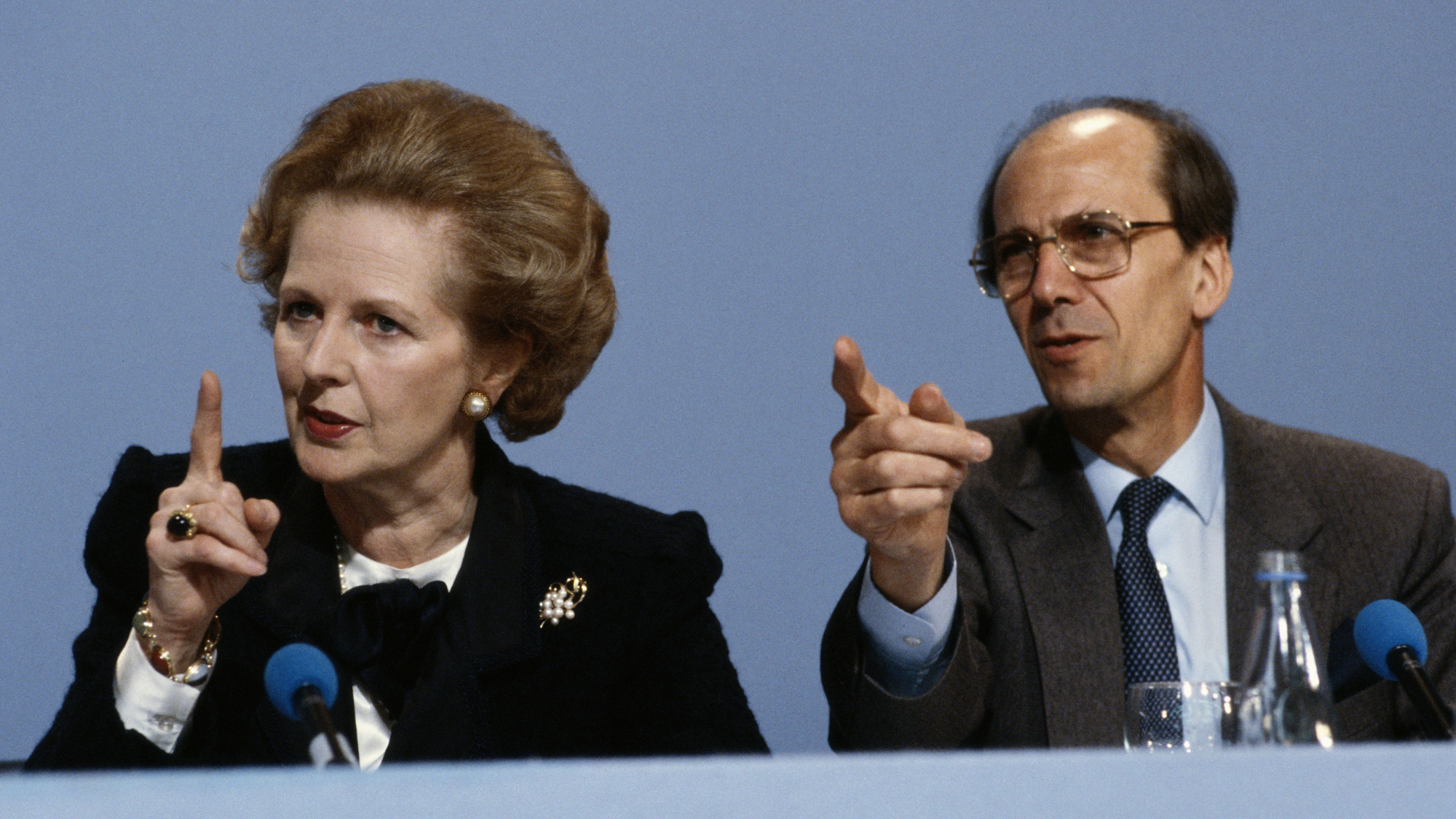

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcer

Norman Tebbit: fearsome politician who served as Thatcher's enforcerIn the Spotlight Former Conservative Party chair has died aged 94

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't