Rebuilding at ground zero

New York officials last year chose a daring design for a new World Trade Center. But rebuilding plans have been caught up in fierce emotion and powerful internal politics. What will actually rise at the site—and when?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What will replace the twin towers?

Many details are still yet to be decided. But this much is clear: Instead of two massive skyscrapers, the new World Trade Center will consist of five buildings arranged around a central memorial space. Their focal point, scheduled for completion in 2009, will be the Freedom Tower. This twisting, tapering skyscraper will rise to a symbolic 1,776 feet, making it the tallest building in the world (the twin towers climbed to more than 1,300 feet). Because few people would want to work in its highest reaches following Sept. 11, the soaring tower will contain only about 70 floors of occupied space, including a restaurant and an observation deck. The top 400 feet will be an open-air superstructure of cables, antennae, and windmills meant to echo the latticework of the Brooklyn Bridge. The steel skeleton will culminate in a 276-foot, offset spire that recalls the Statue of Liberty’s upraised arm. Most critics have hailed the bold design. But getting there has proved tortuous.

Why has it been so difficult?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Partly because of the powerful emotions involved—and partly because there are so many cooks in this particular kitchen. The twin towers were built and owned by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The Lower Manhattan Development Corp. (LMDC), a semipublic entity, is coordinating the actual rebuilding. New York Gov. George Pataki, who serves on both agencies, effectively oversees the process. All these parties have had to contend with family members of those killed on Sept. 11, who have insisted that the footprints of the old towers be preserved. (They will be, and will serve as the anchor of the 9/11 memorial to be built at ground zero, called “Reflecting Absence.”) But it is real estate developer Larry Silverstein, who has a 99-year lease on the site, who is legally entitled to replace all the commercial space that was lost on Sept. 11. That essentially gives him the power to say how it will be done.

Who’s the architect?

There’s the rub, for there is more than one. Last February, architect Daniel Libeskind was designated the official winner of the LMDC’s ground zero design competition. The son of Polish Holocaust survivors, Libeskind had previously won fame for designing the Jewish Museum in Berlin. It was his idea to erect the defiant, 1,776-foot-tall Freedom Tower, to be surrounded by several sharply angular office buildings. But although Libeskind won the contest, he was simply chosen to provide “a design concept” that could serve as the basis for a more detailed architectural plan. As it turned out, Silverstein insisted on the right to name his own architect. He selected David Childs, a more pragmatic man with more experience in designing actual office buildings.

How did the two architects get along?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Predictably, like two scorpions in a jar. Childs and Silverstein sought to tinker with or redo nearly every aspect of Libeskind’s design. They insisted that the five new office buildings be redesigned to replace every inch of the 10 million square feet lost in the twin towers. Childs also proposed redesigning the Freedom Tower to climb to 2,000 feet, but with more floors devoted to office space. Libeskind clung to his plan for 1,776 feet, which is symbolic of the year in which American freedom was born. Every refinement and compromise caused problems, because it affected the size, shape, and placement of the remaining ground zero buildings and other aspects of the site. Libeskind stormed out of at least one meeting; things got so bad that he began bringing his lawyer. Childs’ staff even accused Libeskind’s staff of photographing drawings and models of their confidential designs. An impasse seemed unavoidable.

How was it resolved?

Pataki and Silverstein personally intervened. First, Pataki imposed a deadline. Groundbreaking, he insisted, had to begin by the third anniversary of Sept. 11. (Some say he chose the date because it comes on the heels of the Republican National Convention in New York.) Then, last fall, Silverstein read the riot act to the feuding architects. “There’s no more time for personal or design differences,” he said. “We need to come together.” Childs and Libeskind grudgingly came up with the present plan, with a modified 1,776-foot tower and more conventional office buildings. “I am not the architect of this building,” Libeskind said when the plan was unveiled in December.

What will it all cost?

Rebuilding the entire 16-acre World Trade Center complex will cost about $12 billion. Washington is expected to provide $5 billion to reconstruct the mass-transit hub running below the site. Silverstein is counting on about $7 billion in insurance payments to cover the rest. But he may not get that much. His insurance policy called for him to get $3.5 billion in the event of a disaster. He argues that because two planes were flown into the twin towers, there were two separate attacks and he should receive twice that amount. Last September, a federal judge ruled otherwise and said that Silverstein was entitled to only $3.5 billion. He has appealed, and a final decision will probably be made next month.

When will construction be complete?

The most optimistic estimate calls for final completion by 2013. But the timetable will depend, in large part, on what sort of settlement Silverstein receives. If he loses in court, another source of funding may be needed, introducing another delay. So far, Silverstein is anticipating that things will go his way; he has retained three new architects to design three of the four remaining buildings. But every design revealed so far has sparked sharp public criticism, with resulting modifications. So, fresh battles may soon emerge. “Designing the Freedom Tower,” Pataki said prophetically in October, “will turn out to have been the easy part.”

The race for the top

-

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first time

What to know before filing your own taxes for the first timethe explainer Tackle this financial milestone with confidence

-

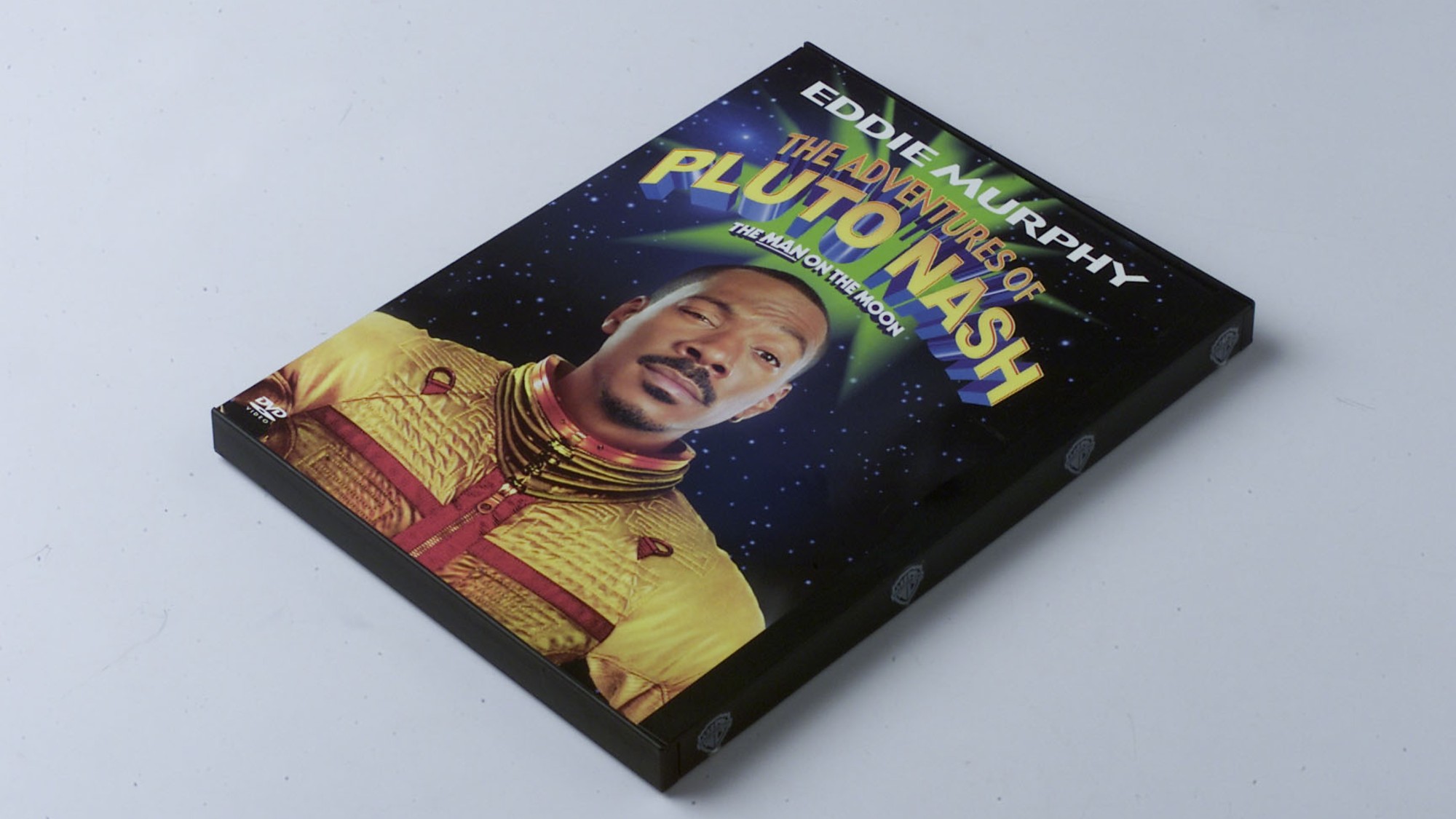

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern history

The 10 most infamous abductions in modern historyin depth The taking of Savannah Guthrie’s mother, Nancy, is the latest in a long string of high-profile kidnappings

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred