The GOP's wrong-headed obsession with the 'Christian candidate'

Christians should vote on candidates' platforms and policies, not their religious rhetoric

Pondering the increasing likelihood of Mitt Romney 2016, Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight recently produced a five-circle Venn diagram of prospective GOP candidates for 2016, aptly titled, "The Republicans' Five-Ring Circus." There was a telling inclusion: "Christian Conservative" was one of the five rings.

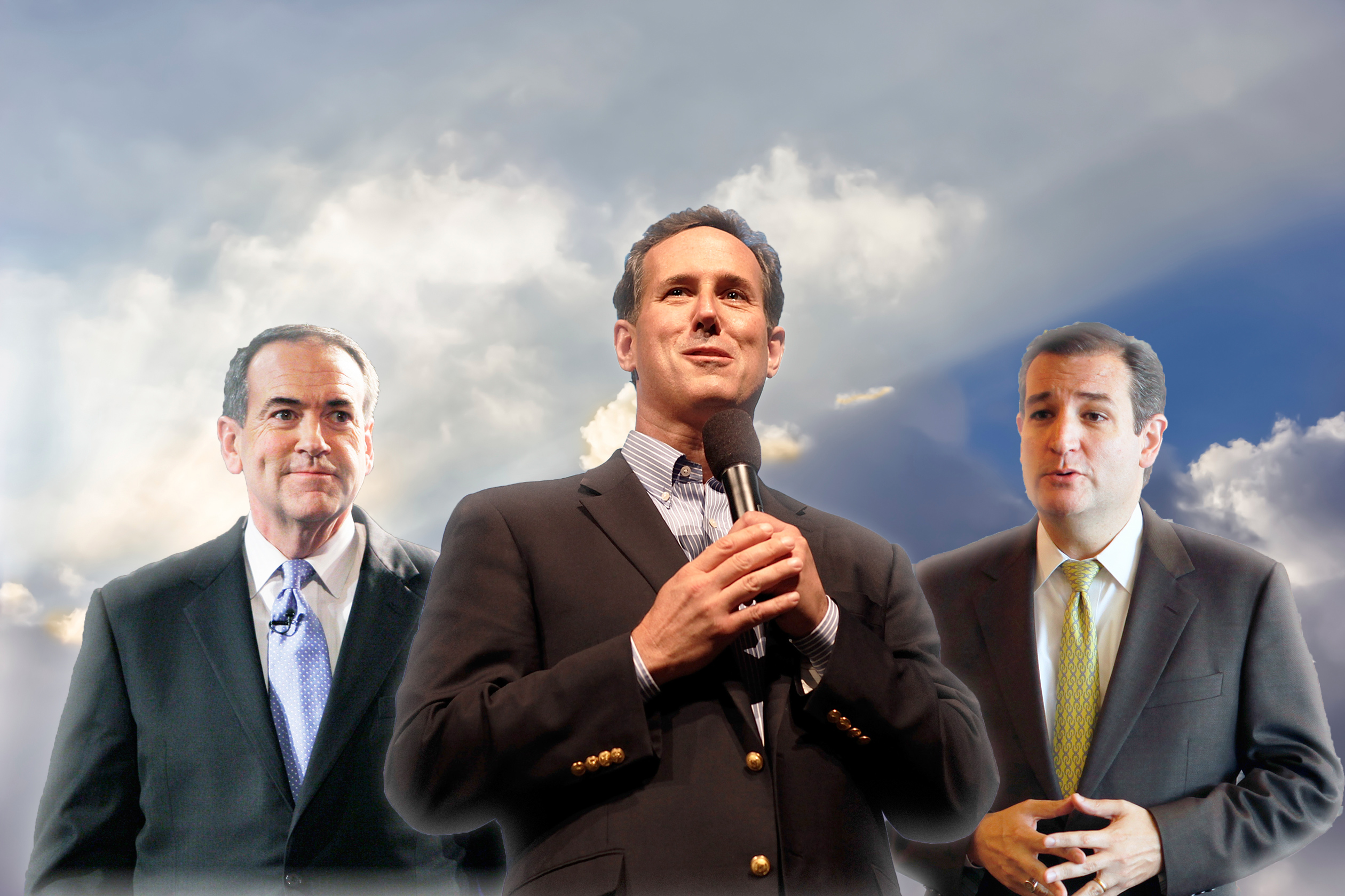

Silver places Mike Huckabee, Rick Santorum, and, to a lesser degree, Mike Pence, Rick Perry, and Bobby Jindal in this Christian Conservative category. I might add Ted Cruz and Ben Carson, at least on the margins, but Silver's labeling scheme is basically right.

Religion matters for Democrats, too. But the awarding of the "Christian candidate" designation is a veritable tradition in Republican presidential politics. Santorum and Huckabee easily claimed this role in the last two elections, and in 2016 it looks like we may get a double (or septuple) whammy. Of course, nearly all GOP contenders profess Christianity, preferably a Protestantism that doesn't stray to any polarizing extremes. But for some candidates, Christianity is less a required feature and more a primary campaign theme.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While the average voter is increasingly less concerned about candidates' religious affiliations — and 2012 showed that most Republicans will vote party line even if the nominee doesn't exactly share their beliefs about God — data from the early primaries in 2012 and 2008 indicate that candidates' profession of religion still makes a big difference for one large chunk of the Republican base: white evangelical Christians.

And thus the GOP's obsession with crowning the conservative "Christian candidate," functionally a nomination process within a nomination process.

So whichever of these men elect to run for president, at least three things are clear:

* They will each attempt to claim the title of this cycle's "Christian candidate."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

* They will each liberally sprinkle Christianese into their stump speeches and ad campaigns, capturing the support of tens of millions of my fellow Christians via the Republican Party's primary form of identity politics.

* They will each fail to win the White House, as all are perceived as too overtly religious to triumph in the general election.

And this entire race to be the GOP's most Christian candidate is so wrong-headed — bad politics and bad theology both.

It's politically damaging for Christian voters because these strenuously religious politicians distract many of us from other candidates who are less overtly churchy, but perhaps more politically appealing. Yes, the "Christian candidates" are opposed to abortion, a key issue for many conservative Christians. But so is every viable contender for the GOP presidential nod. Indeed, these Christian candidates' positions are often based more in their Republicanism than their Christianity. Faithful, orthodox Christians in America (and around the world) hold an almost unlimited variety of political views — and there are strong cases for biblical compatibility with many of them. Huckabee, Santorum, and Co. clearly do not operate out of that diversity. These politicians' agendas are orthodox. But it's a Republican rather than Christian canon with which they comply.

That's not to say that Christians can't support these overtly Christian candidates (though personally I have a number of reservations about them). But it is to suggest that we should be clear about the nature of such support. It's not possible to assess the authenticity and depth of someone's faith from the presidential debate stage, so we should vote on candidates' platforms and policies, not their religious rhetoric.

After all, even the devil can quote Scripture and have conversations with God.

But more important than the political implications of the "Christian candidate" are the grave theological effects this preoccupation produces. The explicit identification of one man as the candidate for Christians to support (and, though this corollary is usually left unspoken, the candidate God supports) fundamentally misdefines what it means to follow Jesus.

This was most succinctly typified by a pre-presidential campaign Mike Huckabee, who in 2004 "took a phone call from God" while on stage at a Republican Governors Association event. The skit featured God telling Huckabee to deliver a message on his behalf (the conveniently vague "Take care of the family, and marriage, and the people of America, and all the people, and the children"). Huckabee replied, supposedly to God's pleasure, "We know you don't take sides in the election" — the audience laughs at such a silly humility — "but if you did we kinda think you'd hang in there with [the Republicans], Lord, we really do."

And thus, while saying the exact opposite, Huckabee in three minutes reduces the Christian God to an American tribal deity and the Christian faith to a tool of political success.

It's a reduction that flies squarely in the face of the conspicuously nonpolitical, universal Kingdom of God that Jesus said he was building. While Jesus proclaimed, "My Kingdom is not of this world," the "Christian candidate" effectively says, "I'm to be the viceroy of God's worldly kingdom."

And while Christianity finds the hope of the world "exclusively in Jesus Christ and the willingness of his people to partner with him in bringing about God's will 'on earth as it is in heaven,'" Huckabee and pals take that job for the government as they promise to "Take care of…all the people" if only we'll give them our vote. That mentality at best misses the central message of the Christian faith, and more often abandons it altogether, subsuming Christianity into the temple ceremonies of the state.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

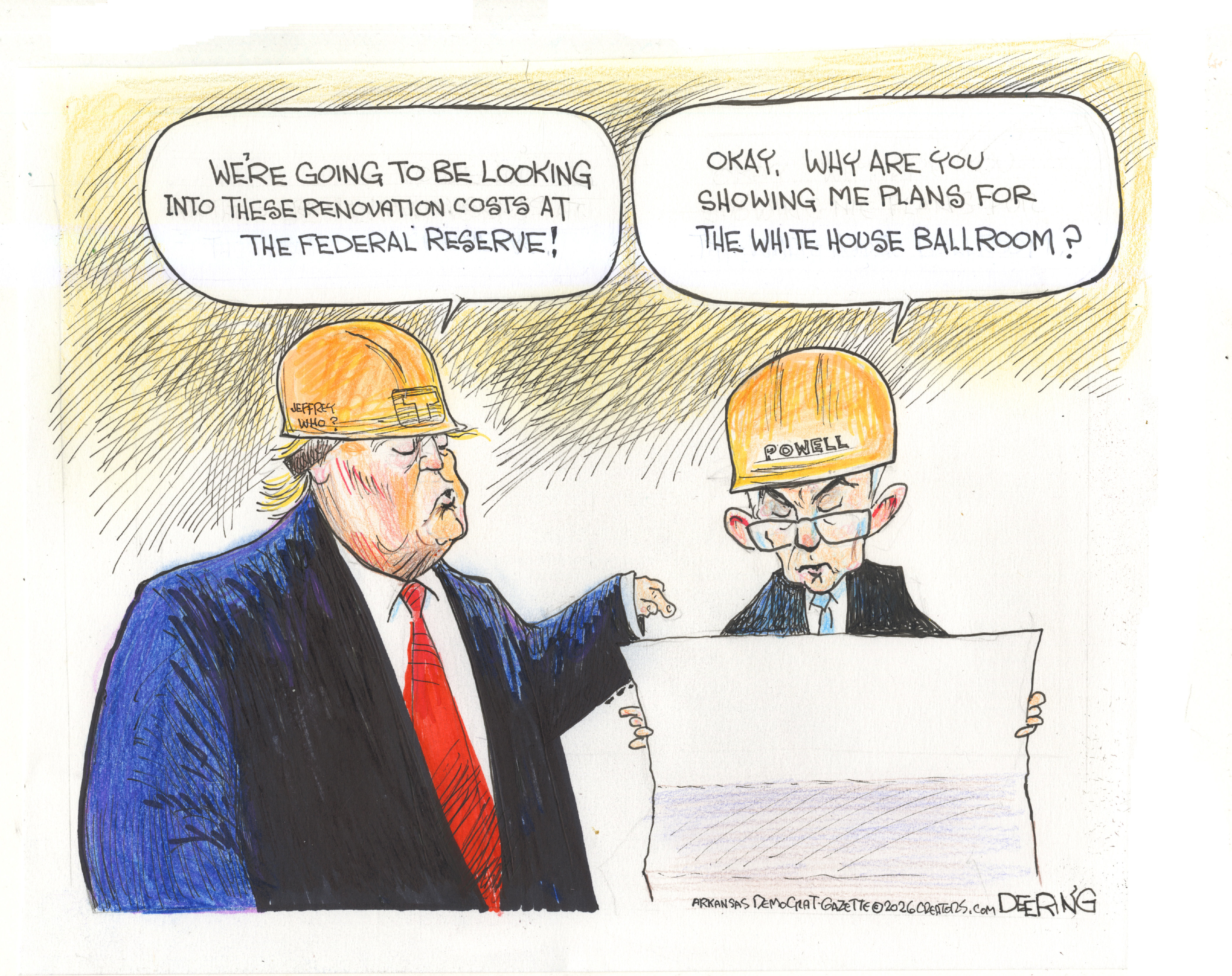

Political cartoons for January 17

Political cartoons for January 17Cartoons Saturday’s political cartoons include hard hats, compliance, and more

-

Ultimate pasta alla Norma

Ultimate pasta alla NormaThe Week Recommends White miso and eggplant enrich the flavour of this classic pasta dish

-

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the US

Death in Minneapolis: a shooting dividing the USIn the Spotlight Federal response to Renee Good’s shooting suggest priority is ‘vilifying Trump’s perceived enemies rather than informing the public’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred