Anti-vaxxers and the death of civic duty

Lost in the great measles debate of 2015 is any sense of sacrifice for the common good

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If last week in Medialand was devoted to arguing over political correctness, this week it was wall-to-wall anti-vaxxers.

Just who are the anti-vaxxers? Oh, who cares — they and their measles-addled kids can go to hell! Wait, maybe they have a point. Nah, they’re just a bunch of paranoid conspiracy-mongers. Well, sure, but what could be more American than that? Maybe that’s why the GOP seems so eager to cinch the 2016 election by drawing on the untapped anti-vaxxer vote. Oh, yeah, then why is Rand Paul getting an injection in this picture? No idea, though at least Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton came down on the right side of the issue from the start. Yeah, what profiles in courage; too bad Obama’s a late convert to good sense. Fine, but what’s John McCain’s excuse?

The chatter has been entertaining, as always.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But it’s also a distraction from the deeper social and cultural issues raised by the whole episode.

In calling out the anti-vaxxers, our leading public figures and opinion journalists have invariably used the language of self-interest: “Vaccines work.” “Getting your children vaccinated is worth it.” “Don’t let your kids get sick!”

This is all fine and good, but it also doesn’t quite make sense: it’s the kind of rationale that’s appropriate when a vaccine for a deadly infectious disease has just been approved. That’s when public-health authorities need to spread the word that it’s far better for you and your loved ones to take the vaccine than merely to hope for the best against the contagion.

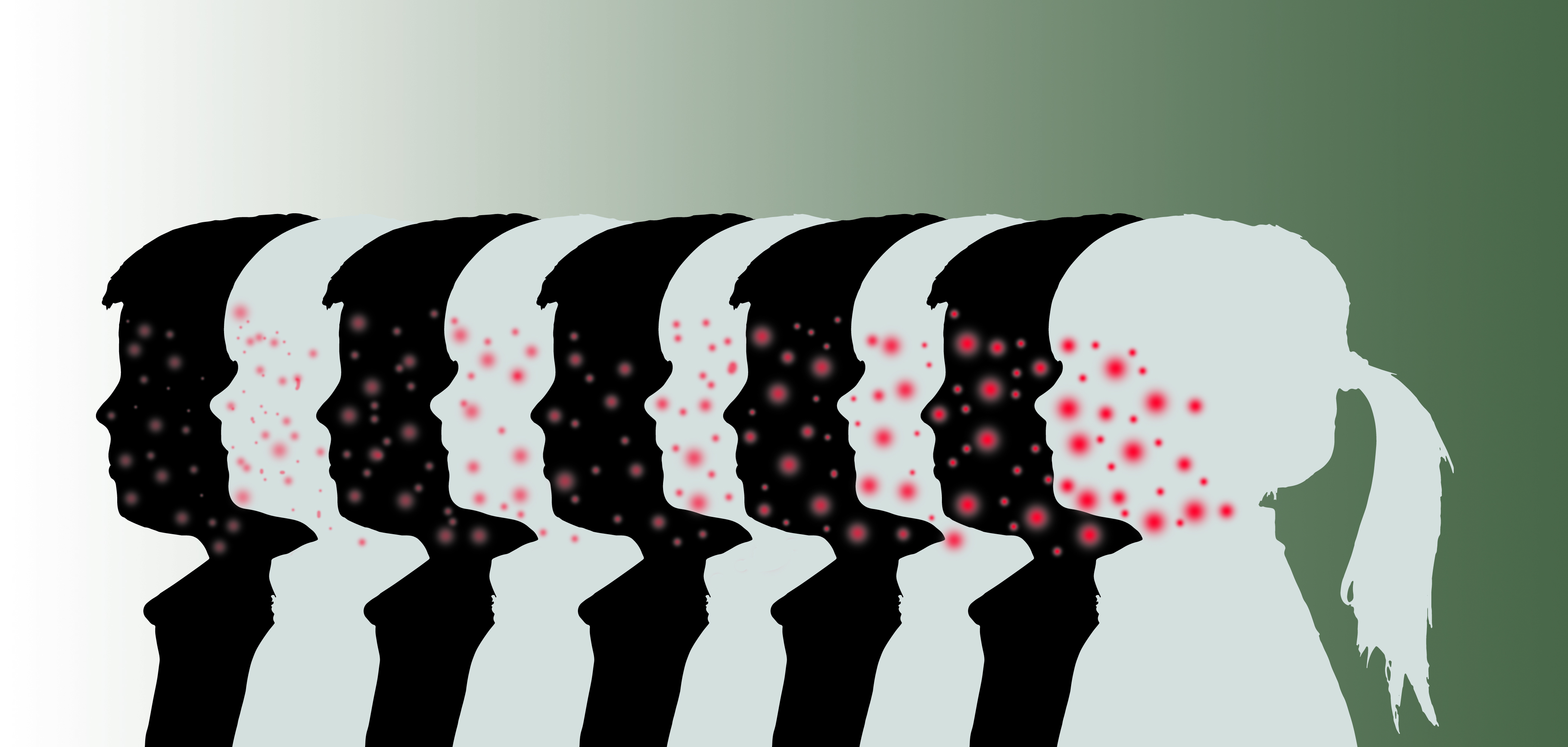

But that’s not the situation today, when thanks to herd immunity brought about by decades of vaccine taking in the United States, there’s a very low chance of any particular person contracting measles (or other formerly widespread infectious diseases), whether or not that person has been vaccinated.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As many this week have pointed out, that presents a collective-action problem: if there’s any (real or imagined) cost at all to you as an individual opting for vaccination, noncompliance is perfectly rational. Just free-ride and you’ll likely be fine. Only if large numbers of people make the same rational calculation will the noncompliance become personally dangerous to noncompliers.

The trick for public officials, then, is persuading people not to become free riders.

One option is coercion: force people to get vaccinated under penalty of law.

But there’s also a less draconian option: persuade Americans not to free-ride by using a different form of reason and rhetoric — one based not on calculations of self-interest narrowly defined but on civic appeals. Obligation and duty, honor and sacrifice for the common good — this is the language of citizenship. And to judge from its almost total absence from the anti-vaxxer debate, it is rapidly dying out.

Its passing is easy to miss, since politicians of both parties still make nominal gestures toward collective goods and ideals.

Republicans specialize in over-the-top patriotic evocations of national greatness and American exceptionalism. But when we drill down into these nationalistic appeals, they quickly dissolve into pointillism: America is great because it allows hundreds of millions of individuals to disconnect from all collective purposes and pursue happiness in their own private little worlds. For Republicans, there’s increasingly no sense of the dignity and nobility of the public sides of our lives. The nation isn’t greater than the sum of its parts; it’s just the sum total of those parts.

Democrats do somewhat better. Just last month in his State of the Union address, Barack Obama spoke of Americans as members of a “strong, tight-knit family.”

But that’s not quite right, either. Of course we’re not literally members of a family. I would willingly lay down my life for my wife or children in a heartbeat, without a second’s thought. Nothing would feel more natural. Do I feel the same willingness to sacrifice for every one of the 318 million people who happen to be citizens of the United States? Of course not. Soldiers can be trained to feel and act that way, but it doesn’t come naturally to them either — and a liberal democracy shouldn’t require anywhere near that level of commitment on the part of its civilians.

Yes, we care more for Americans living thousands of miles away from us than we do for citizens of other nations. But that attachment can’t compare to the spontaneous love and devotion we feel for immediate family members. It’s just not the same.

If Republicans end up denying any independent value to our collective, civic lives, Democrats run the risk of collapsing the distinction between the private and the public, the family and the nation, altogether. What both positions end up rejecting, for opposite reasons, is the need for a rich language of civic duty — precisely the language that could make a case for voluntarily setting aside one’s private, personal interest and good for the sake of the public interest and common good of the political community as a whole.

Citizenship can mean and has meant many things down through the centuries, but it nearly always involves individuals freely taking communal responsibility for the shared dimension of their lives — the parts of them that take place in public spaces, on streets, on roads, in stores, in schools, in workplaces, and in genuinely collective endeavors (wars, public works, and charity).

In the most pressing cases of civic need, the government may coerce the sacrifice of citizens for the common good. The military draft, which sends citizens to their possible death regardless of whether they wish to fight and die, is the most egregious example. But in less urgent circumstance, public officials can appeal to the civic duty of citizens using public-spirited rhetoric.

That’s what’s been missing during the anti-vaxxer debate.

Just think of how oddly refreshing it would have been to hear a politician say something like the following during the past few days: “If there were compelling scientific evidence that vaccines were harmful, then of course I would welcome a debate about the wisdom of taking them. But doctors tell us there is no evidence strong enough to outweigh the great public good they have done over the past several decades, creating a nation far freer of contagious diseases than it was a century ago, with far fewer of our fellow citizens dying in pain and fear and far too young. You owe it to your children — but you also owe it to America — to vaccinate your children.”

There’s no reason for a Democrat not to talk this way.

There’s no reason for a Republican not to talk this way.

Hell, there's no reason even for a libertarian like Rand Paul not to talk this way.

It used to be called moral suasion — the use of reason and rhetoric to inspire citizens to acts of civic virtue.

It sounds so old-fashioned. So quaint.

But that doesn’t mean we can get along without it.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.