The puerile fantasy of regime change

Finally, the era of regime change is over

When it comes to the Islamic State, the inconsistency of our naming conventions seems a trivial matter relative to the extremist group's fearsome brutality. But our words still matter.

President Obama insists on calling it ISIL; most of the rest of us call it ISIS. But the real source of our careful terminological choices is hiding in plain sight. Not only are some of us, like the president, keen to downplay the Islamic identity of the Islamic State. All of us, when you think about it, are pretty uncomfortable with the admission that the Islamic thing in question is a state at all.

Here, in the second decade of the 21st century, we are reluctant to say aloud that people have organized with devotion under bad regimes. We do not relish the thought of the state, a stubbornly 20th-century institution, intruding back onto the post-9/11 world we at last had adjusted to.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

More than a mob, a trend, or a network, a state is a top-level political organization. Instead of conforming to the rule of a guru, a boss, or a mastermind, it is controlled by a regime. It presents the kind of challenge to statecraft that the West had done all in its power to put behind us. From that standpoint, the viciousness and depravity of ISIS should not define it in our minds. Rather, we rightly think of ISIS as the regime that manifests one of the West's greatest misfortunes and disappointments of the past 25 years. Thanks to ISIS, it must now be said that the era of regime change is over.

There is no changing the ISIS regime. The Western establishment understands that the whole state must be, as the president says, "degraded and ultimately destroyed." This is an epochal shift in the way we conceptualize the use of force. And no matter how halting, depressing, or embarrassing, it is a blessing in disguise.

As a policy, regime change was a failure, rooted in fundamentally incorrect and misbegotten ideas about how the forces of economics and history could be leveraged in the post-Cold War world, and how the West could project power to achieve transformative victories with a minimum of blood and treasure.

Despite a rolling thunder of hemming and hawing about our strategy toward ISIS, absent from the conversation — conspicuously absent — is any discussion of "decapitating" its leadership, or overthrowing its ruling cabal, or double-tapping its charismatic, reclusive leader, or any of the other tactics and tropes that defined regime change as the West's signature approach to rogue states over the past two decades.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is progress. We have learned, belatedly and the hard way, that regime change malfunctioned as a model when applied to 21st-century adversaries like al Qaeda. That was more intuitive than we cared to admit. Killing Osama bin Laden was hardly a masterstroke. It was, justifiably enough, a matter of avenging our civilian dead and gratifying our sense of valor. But the case for regime change had begun to unravel before bin Laden was killed, and afterward it began to disintegrate. The idea that the problem of Iraq could be solved by regime change nourished all manner of dangerous delusions. The determination that regime change had become necessary in Libya set in motion a black mass of anarchy that has no end in sight, providing welcome news only for ISIS itself.

Regime change in Egypt has been a disgrace; regime change in Cuba, a pipe dream. State Department officials are now in headlong retreat from the very idea of regime change in North Korea, banking on the kind of calculated "opening" adopted by the junta in Myanmar. Perhaps most humiliating of all, however, has been the carnival of incompetence and half-measures surrounding our foolish attempt at regime change in Syria. Disgrace crushed our hopes to use liberated Benghazi as a lily pad for arming the Syrian rebels. But something worse than disgrace has accompanied the administration's convoluted and incomprehensible intention to replace Bashar al-Assad with something or someone better.

There are those who say that regime change is in fact the best of a bad lot of options. The Brookings Institute's Michael Doren has made this case with an eye toward Syria. Because Damascus is the key to "the central battle in the conflict over the new order in the Middle East," he writes, pursuing regime change will at least manage to make the U.S. "the dominant voice in all Syria discussions" conducted with Russia, Iran, and other geostrategic adversaries.

To be sure, neoconservatives and other interventionists do well to recast their bold agenda in accordance with America's very narrow field of political and military options, both in the Mideast and around the world. Indeed, the vision of regime change that emerges from such a reconceptualization is profoundly different from the notion that commanded almost reflexive bipartisan support over the past generation. Back then, the logic of regime change presumed that military action could cleanly and concisely catalyze a process of Westernization that was all but waiting to happen, thanks to the inexorable force of globalization and democratization. We now know this to be a fantasy.

As a result, some Americans have the stomach for a return to the intrigues and shadow play that characterized the Cold War era of regime change, wherein coups and CIA operations carved client states out of a hostile world caught in one big zero-sum game. Most Americans, however, are better prepared to revert to America's classic prudential cynicism: Unless you go big, don't go at all; and once you're done, go home.

James Poulos is a contributing editor at National Affairs and the author of The Art of Being Free, out January 17 from St. Martin's Press. He has written on freedom and the politics of the future for publications ranging from The Federalist to Foreign Policy and from Good to Vice. He fronts the band Night Years in Los Angeles, where he lives with his son.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

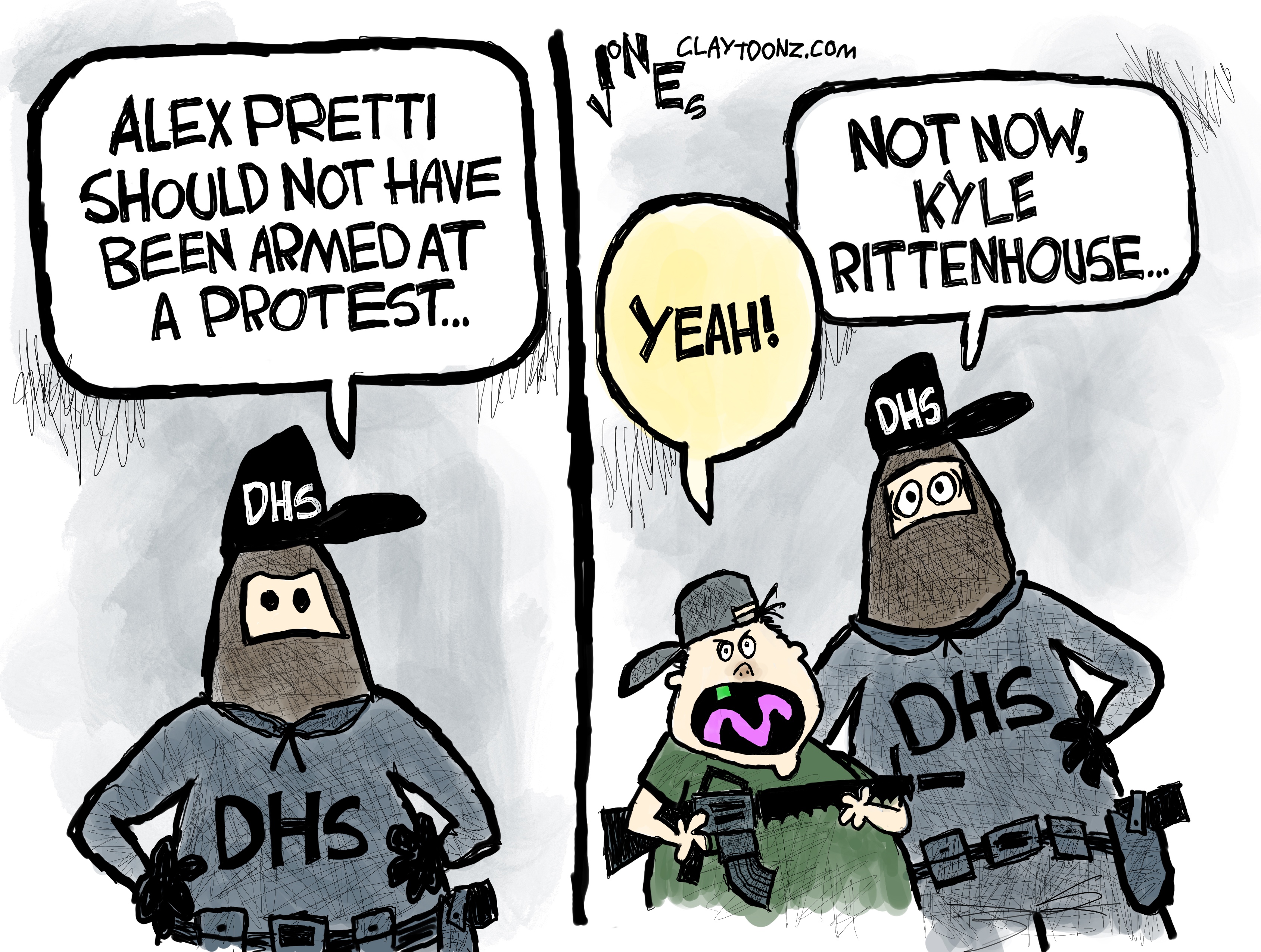

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blog

Late night hosts joke about Trump's forced exodus from Facebook to blogSpeed Read

-

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.

Fox News admits Biden doesn't actually want to cancel meat. Late night hosts pounce anyway.Speed Read

-

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickers

Manhattan D.A. will stop prosecuting sex workers, not their clients, pimps, or sex traffickersSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worse

John Oliver explains personal bankruptcy, how credit card lobbyists and lawyers make it much worseSpeed Read

-

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attention

John Oliver explores problems with U.S. nursing homes and long-term care, suggests you pay attentionSpeed Read

-

John Oliver tries to explain whether you should worry about the enormous U.S. national debt

John Oliver tries to explain whether you should worry about the enormous U.S. national debtSpeed Read

-

Late night hosts laugh at the giant ship blocking the Suez Canal, chide Fox News for fake Kamala Harris scandal

Late night hosts laugh at the giant ship blocking the Suez Canal, chide Fox News for fake Kamala Harris scandalSpeed Read

-

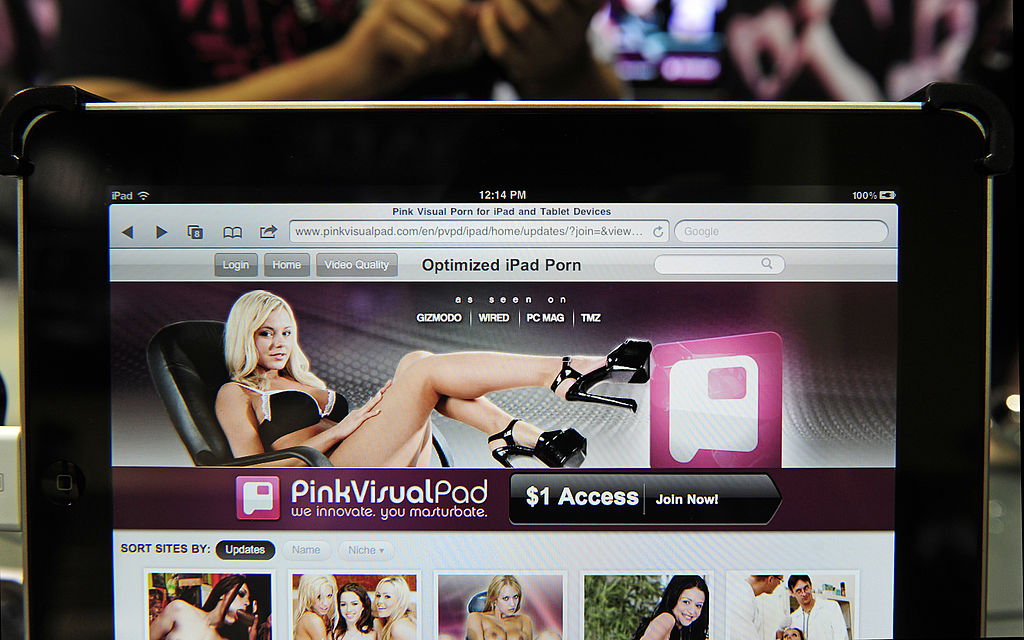

Utah governor signs bill requiring porn blocking on all new smartphones and tablets

Utah governor signs bill requiring porn blocking on all new smartphones and tabletsSpeed Read