How to get Americans to trust Wall Street again

Regulating insider trading isn't easy. Good thing we have other options.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

To many Americans' eyes, financial markets have become a mercurial and opaque system in which money is frantically moved around for no particularly clear or good purpose for the common economy. Quite often the only beneficiaries seem to be the rich and powerful. No less than 64 percent of voters believe the stock market is rigged against them.

Take insider trading: profiting by shuffling stocks and securities around based on privileged information not available to the public. Even Wall Street professionals seem to think their industry is rife with it.

"Insider trading makes our markets less fair, hurting families' ability to save and deterring regular investors from entering the market," says Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), co-author of a bill that seeks to definitively outlaw the practice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Bloomberg View's Matt Levine isn't exactly a fan of these new bills, arguing that the language of the Senate bill is so broad and ill-defined as to be conceptually unworkable. On that point, he may well be right. But the moral instincts of American voters and their representatives, like Menendez, deserve to be respected and acted upon.

Now, there's no actual law against "insider trading." It's a species of crime that's grown out of the jurisprudence around securities fraud law. And it really is hard to define. At what point does a golf course conversation between two buddies who happen to be Wall Street traders stop being regular banter that might happen to include stuff about work and become a prosecutable offense?

The House bill attempts a clear definition with lots of caveats. Levine isn't a big fan, but his rundown makes it seem like the bill does an admirable job grappling with grey areas. The Senate bill, from Menendez and Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.), is a much blunter instrument. Levine worries it would criminalize most any information advantage, no matter how banal or part and parcel of working on Wall Street. The guts of his complaint go like this:

These information advantages add up to the profession of investing. The point of investing is trying to get information that other people don't have, and use it to buy and sell securities. That's how markets work: People who want to make money trading securities have an incentive to find out information, and then use it to buy and sell securities, which causes the prices of those securities to incorporate that information, which makes markets efficient. Which makes it safe for regular families to invest: They know that if they buy Apple stock, its price incorporates all the information that people in the market can ferret out, and so reflects Apple's prospects as fairly as possible. [Bloomberg View]

Now, whether you buy the efficient markets hypothesis is its own can of worms. And if we passed Reed-Menendez, a lot of its conceptual difficulties could be worked out in the give-and-take of jurisprudence. Nevertheless, let's roll with Levine's logic.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

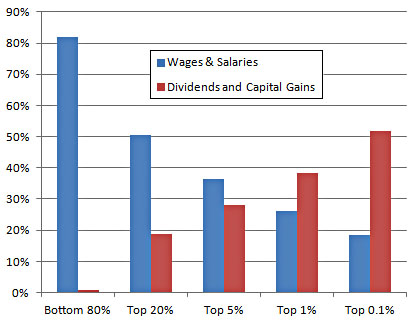

The first thing to note is that if Wall Street's ultra-complex, ultra-sophisticated trading makes investment safer for everyday Americans, the benefits of it are pretty thin. In 2006, the bottom 80 percent of tax filers got all of 0.7 percent of their income from capital gains and dividends.

Which shouldn't be surprising, given that wealth ownership is insanely skewed in this country, and revenue from this wealth contributes more to inequality than any other source. Even if that ultra-complex, ultra-sophisticated trading is making investment safer for the average American, the average American still doesn't get to participate all that much.

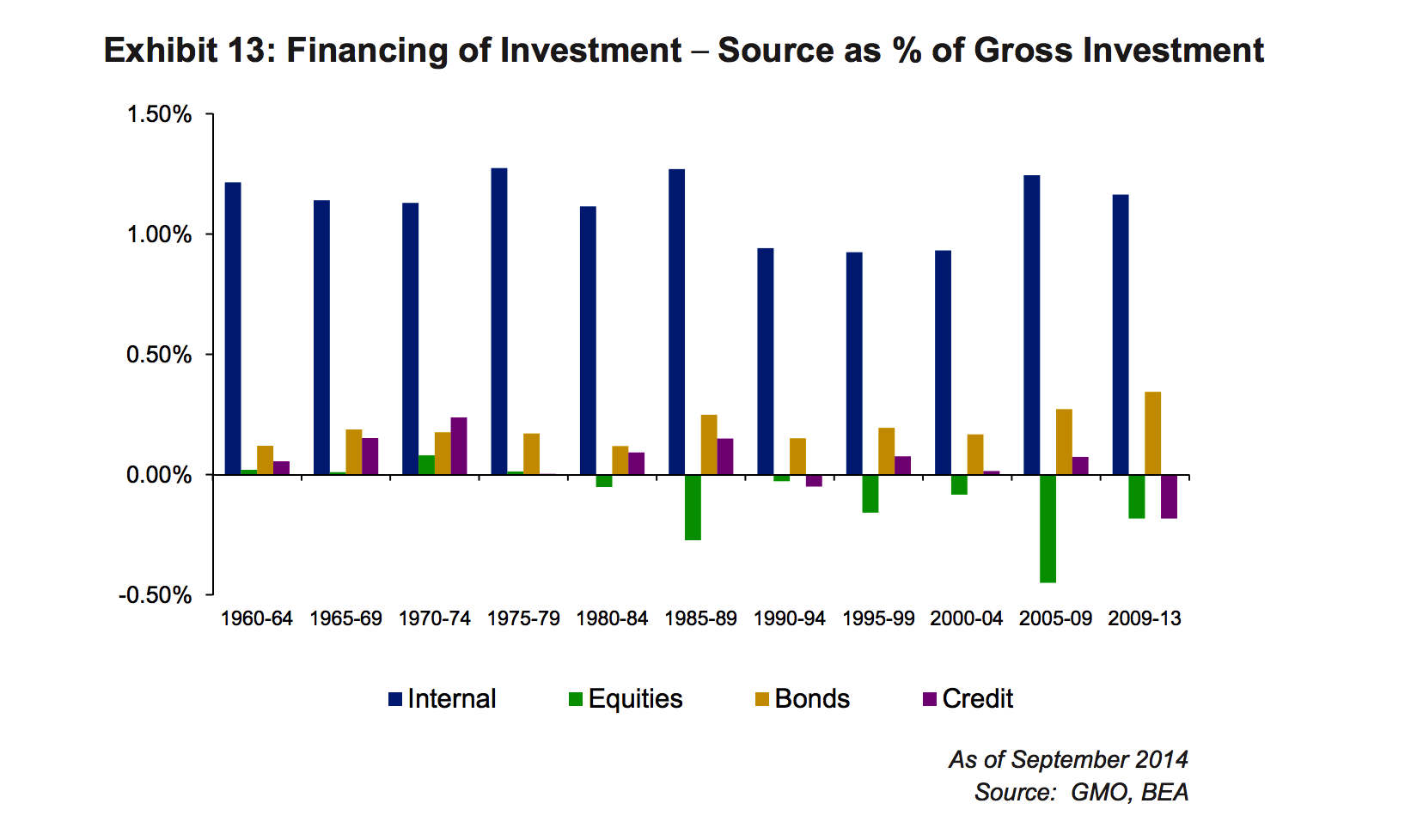

But doesn't that trading also mean financial markets are disciplining companies better, moving more money to successful ventures and pulling more out of failing ones? Probably not. Firms have never raised more than a small sliver of their investment from equity. And as you can see from this chart, equity has become a net drain on firms' finances since the stock buyback revolution took off.

Publicly traded companies are disciplined by the same market forces that discipline privately held companies. If they successfully produce a good or service people want, they'll make revenue and their internal finances will hold together. If they don't, they won't.

Which gets to one of those weird economic truths people rarely mention in public: It's not entirely obvious why the stock market exists. It doesn't really seem to do businesses much good, and Lord knows it isn't helping the average Joe. It seems to mainly be an extractive cash machine for the wealthy. And given that the era of Wall Street preeminence, stock buybacks, and shareholder capitalism has also been the era of rising inequality, the collapse of broadly shared prosperity, and the gutting of middle-class jobs, you can hardly blame people for looking askance at anything with the whiff of insider trading about it.

If Levine is right that the bills are unworkable, we should find other ways to make sure all that ultra-complex, ultra-sophisticated trading is actually serving the common good again.

We could start with a financial transactions tax. Then we could start taxing capital gains more, or like regular income. In that case, we'd want to lower the corporate income tax to encourage growth. Alternatively, we could keep capital gains taxes lower and jack up the corporate income tax while clearing out its loopholes. That would encourage firms to plow more of their money back into investment and job creation, since that avoids the corporate income tax entirely, and money has to pass through that tax before it becomes a capital gain.

But the best tax would probably be one on stocks of wealth themselves. That would raise revenue, but more importantly, it would make big concentrations of wealth less attractive, and encourage a broader distribution of stock ownership.

We could also expand the use of sovereign wealth funds. That would turn more of the stock market into a publicly held trust, which would then disperse whatever revenue it makes back out to Americans at large.

All of this requires creativity and political courage, not to mention mass mobilization of voters. But if we can get those things, it's not like this country doesn't have options.

In the end, if you want Americans to trust financial traders, you need to make sure the trading they're doing is actually adding to rising and shared prosperity.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred