What would a worker-friendly Trans-Pacific Partnership look like?

It won't be easy to achieve

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

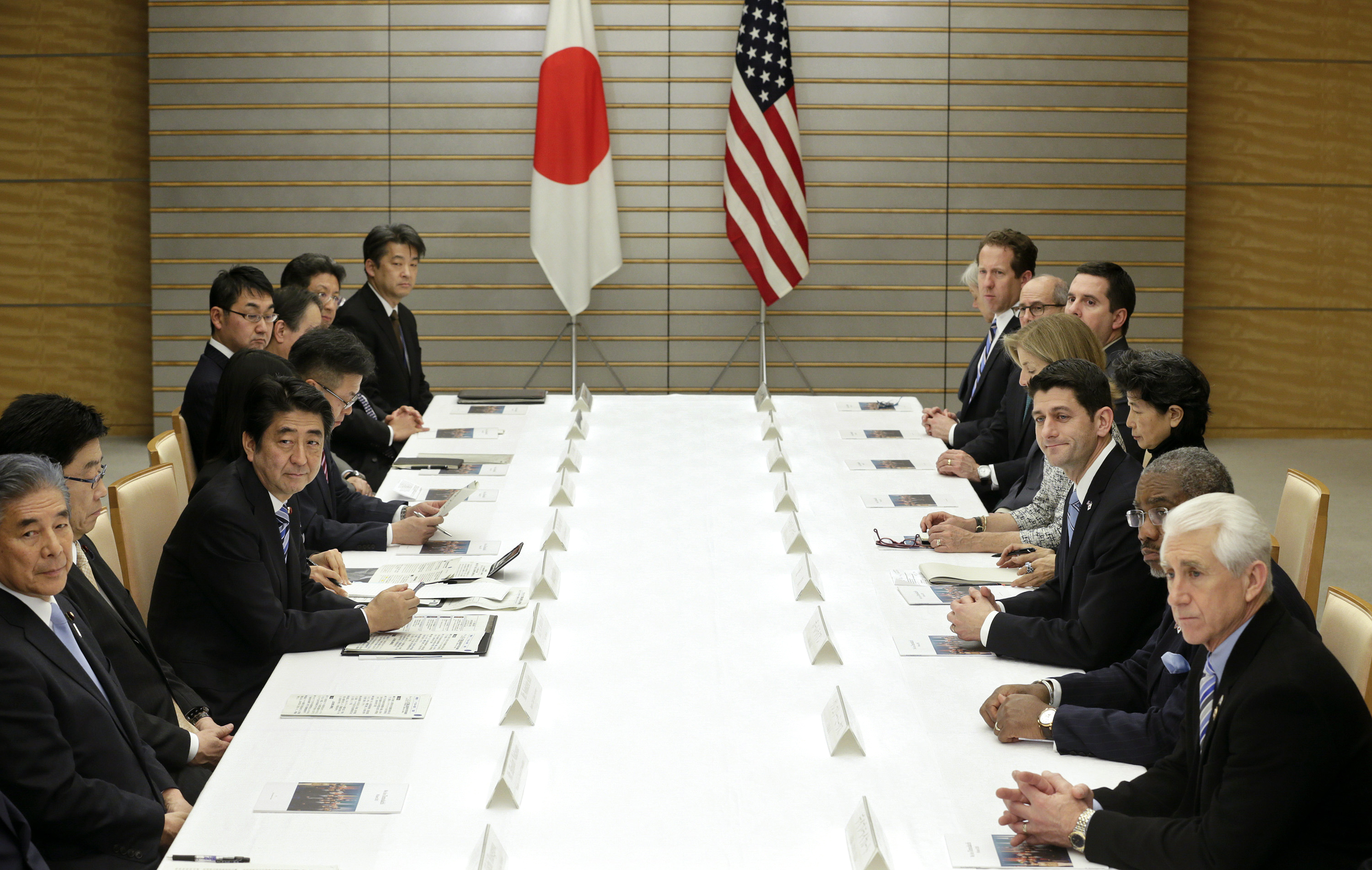

The Trans-Pacific Partnership — the big free trade deal the Obama administration is trying to hash out with 11 countries around the Pacific Rim — has skeptics on both sides of the aisle. Perhaps that's why economists and writers like Larry Summers, Brad DeLong, Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and Ezra Klein have all taken shots at figuring out the TPP's merits.

The biggest potential problem with TPP is that past international trade deals have eroded middle-class jobs, particularly in manufacturing, while increasing incomes at the top, thus creating even more of an hourglass economy. Such concerns are balanced against the possibility of a genuine gain to the American economy, and the chance to get other countries to enact tougher labor and environmental standards.

But given how low America's trade barriers are already, it's hard to see how much more economic uplift the TPP could squeeze out, for the U.S. or anyone else.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At any rate, Krugman — a soft "no" — observed that Summers — a soft "yes" — bases his thinking more on what the TPP could be than what anyone actually knows about its contents. So what would a worker-friendly TPP look like? Here are three points to keep in mind.

Will currency manipulation hurt American workers?

Currency manipulation occurs when one country drives the value of its currency down vis-a-vis other currencies, thus giving it an edge in exports. A lot of elites worry that "currency manipulation" is hard to define, and rules against it in the TPP would interfere with sovereign control over monetary policy, since monetary decisions inevitably also affect the value of currencies.

But Robert Scott, an economist with the Economic Policy Institute, thinks there's a relatively reliable way to get to a shared definition of currency manipulation, largely by setting rules for how many assets denominated in a foreign currency a country's central bank or other government institutions can hold. For example, only a very small portion of the U.S. Federal Reserve's balance sheet includes assets denominated in foreign currencies, while Japan holds considerable assets in U.S. dollars.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

These sorts of imbalances in who holds how much of whose assets affect global money flows, and there's considerable evidence it's a big — possibly a very big — factor in the size of America's trade deficit. That deficit in turn sucks demand out of the American economy, which has tended to eliminate middle-class jobs.

Some quick and dirty calculations by Baker suggest that — barring an effort to lock down rules on currency manipulation — the TPP's effects on the trade deficit could overwhelm other gains.

Will new copyright protections hurt middle-class workers?

One of the big complaints voiced by a lot of major players — media companies, pharmaceutical firms, the tech and internet industry, etc — is chaotic enforcement (or, rather, non-enforcement) of copyright protections overseas. That's certainly an argument for using the TPP to standardize copyright and patent protection across all the countries involved, and to get enforcement up to snuff. But it's not necessarily an argument for the length of patents and copyrights to be further extended. Standardization could just as easily converge on a reduction in length.

In strict economic terms, longer patents and copyrights increase monopoly rents. We're not paying big companies to do something productive, we're paying them so we can. That's going to bring more money into the American economy, though mainly to the top. But it will also make the world a bit poorer, especially the already-poorer people abroad who will be paying the increased fees and prices on things like medicine, music, movies, software and more. Those incoming payments could also crowd out exports in industries like manufacturing that support middle-class jobs. Baker estimates the hit could be as much as 40 percent of any gains in income workers could see from the deal.

Those same protections for drugs in particular also drive up the costs of programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and mean health care eats up more of the average American household's budget.

How can the TPP's gains be spread evenly at home?

The New York Times' Eduardo Porter argued that European countries have dealt with the challenges of international trade by bulking up their safety nets and other social democratic programs like unemployment insurance, paid leave, etc. Those institutions spread the net gains to their economies more evenly amongst their workers, and shield them from job dislocations. In fact, the big way most Western countries have increased incomes for their lowest 10 percent of citizens in the last few decades is increased transfers.

So we could just tie passage of the TPP to a permanent increase in the generosity of unemployment insurance, or to nationally mandated paid sick leave and paid family leave, or to expanding the generosity and applicability of the Earned Income Tax Credit, or some similar move.

Now, as DeLong rightly notes, this discussion is all hand-waving until we actually see the text of the TPP.

The Obama administration seems pretty convinced it needs to "fast track" authority to even keep the negotiations alive long enough to arrive at a final text. Even if they do get it, they'll still have to show Congress the finalized language for an up-or-down vote to occur. The White House is insistent that skeptics will be pleasantly surprised be the final language.

Maybe. Klein also says the unions are pretty familiar with what's been negotiated already and still aren't onboard. It's possible they're being obstinate.

But given that everything in the list above would require elite Americans, corporations, and businesses interests to minimize their own gains in order to maximize gains for workers and less fortunate Americans — and given the current distribution of wealth and power in America, and how that plays out in political decision making — does anyone really think that outcome is remotely likely?

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day