America is not great: What the Baltimore riots exposed

The idea of American exceptionalism took a mighty blow this week

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I love my country, but I'm tired of hearing about what an "exceptional" nation we are. Not just exceptional in the sense of different, distinctive, unique. We are that in lots of ways, many good, some quite bad. What I mean is the sense of "exceptional" that permeates the speeches of our politicians, especially Republicans, and the rhetoric of our right-wing rabble-rousers on talk radio and cable news.

Patriotism — love of one's own political community — is a natural human sentiment. But if it is not to be childish, delusional, partial, blinding, it must be tempered with a willingness to face facts, even when they're ugly.

There's an awful lot of ugliness in Baltimore right now.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's the same kind of ugliness we saw in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, last summer; in North Charleston, South Carolina, earlier this month; and in numberless incidents of African Americans suffering blatant injustice at the hands of private citizens and armed agents of the state going all the way back to the era of Jim Crow, and further back to the very beginnings of America, long before the country was founded as an independent nation.

"But wait," ask the commentators. "What about the rioters? What good is served by attacking police officers and burning down poor neighborhoods? Aren't you making excuses for their lawless violence?"

Good questions. Before thinking about the answers, I want to make a series of concessions to those inclined to pose them.

Yes, order needs to be restored.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Yes, many police officers are decent people who mean well.

Yes, their job is dangerous and demands great courage (probably more than I could muster).

Yes, it's terrible that, as of Tuesday afternoon, 20 officers have been injured.

Yes, it's horribly counter-productive when protests become violent and lead to the destruction of property (and injury to persons) in impoverished communities.

Yes, some indeterminate number of the rioters are thugs who are treating the thus far unexplained death of Freddie Gray while in police custody as an excuse to loot and otherwise wreak havoc.

All true.

Now let me pose a question of my own:

How many white Americans hear anything a little off, anything unfeeling, anything the least bit galling in the following statement, delivered by Baltimore police spokesman Capt. Eric Kowalczyk late Monday afternoon?

Our officers are working as quickly and as appropriately as they can to bring about order in the area of Mondawmin and affect arrest of the criminals who violently and without provocation attacked our police officers.

Kowalczyk seems like a excellent spokesman. He's young, handsome, articulate. He's also white.

I wonder if an African American spokesman would have uttered the words "without provocation." I tend to doubt it.

Did the specific officers pelted by rocks and bricks on Monday afternoon provoke the specific black boys and men who hurled them? Probably not. In that sense, Kowalczyk was correct; the attacks were "without provocation."

But of course the attacks were not at all without provocation.

The provocation has been going on for centuries.

It bubbles at a simmer every day in urban ghettos wracked with drugs and violent crime, starved for decently paying jobs, and saddled with dysfunctional, underfunded schools and other social services.

It reaches a rolling boil every time a renegade cop decides to abuse his authority by delivering a beating to or planting drugs on the citizens he's supposedly empowered to protect, knowing that he'll almost certainly get away with it — because almost no one in a position to do something about it cares enough to intervene.

And every now and then it boils over, when the injustice simply becomes too much to bear — when an unarmed man accused of a minor offense is choked to death by a cop, or when an officer shoots and kills an unarmed man eight times in the back, or when an unarmed man in police custody mysteriously ends up with a nearly severed spinal cord and then dies of his injuries.

Viewed from outside the self-congratulatory ideology of American exceptionalism, it can look suspiciously like the United States is conducting a sadistic experiment to see just how much injustice, how much indignity, how much abuse one group of people will endure before they lash out in rage. The answer appears to be: an awful lot.

The pattern has been repeating itself for at least a century. Chicago, 1919. Watts, 1965. Detroit, 1967. Los Angeles, 1992. Cincinnati, 2001. Ferguson, 2014. In each of these times and places (and many more), pressure slowly builds over weeks, months, and years; an event serves as a spark to unleash the pent-up fury in spasms of violence and destruction; and then relative calm returns.

And nothing really changes.

And that, more than anything, is what really deserves to dispel the feel-good pretenses of American exceptionalism.

If there is one thing we can know with absolute certainty about this week's events in Baltimore, it is that they will not be the nation's last act of racial insurrection. There will be more riots, more injured cops, more arrests, more black men thrown in jail, and more stores looted and burned to the ground, if not next week then next month or next year — because there will be more egregious acts of injustice committed against the African American population of the United States.

We know this just as surely as we know the sun will rise tomorrow.

We know this because at some level we're aware, and willing to accept, that this is just the way things are in America.

That doesn't sound very exceptional to me.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Sean Bean brings ‘charisma’ and warmth to Get Birding

Sean Bean brings ‘charisma’ and warmth to Get BirdingThe Week Recommends Surprise new host of RSPB’s birdwatching podcast is a hit

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

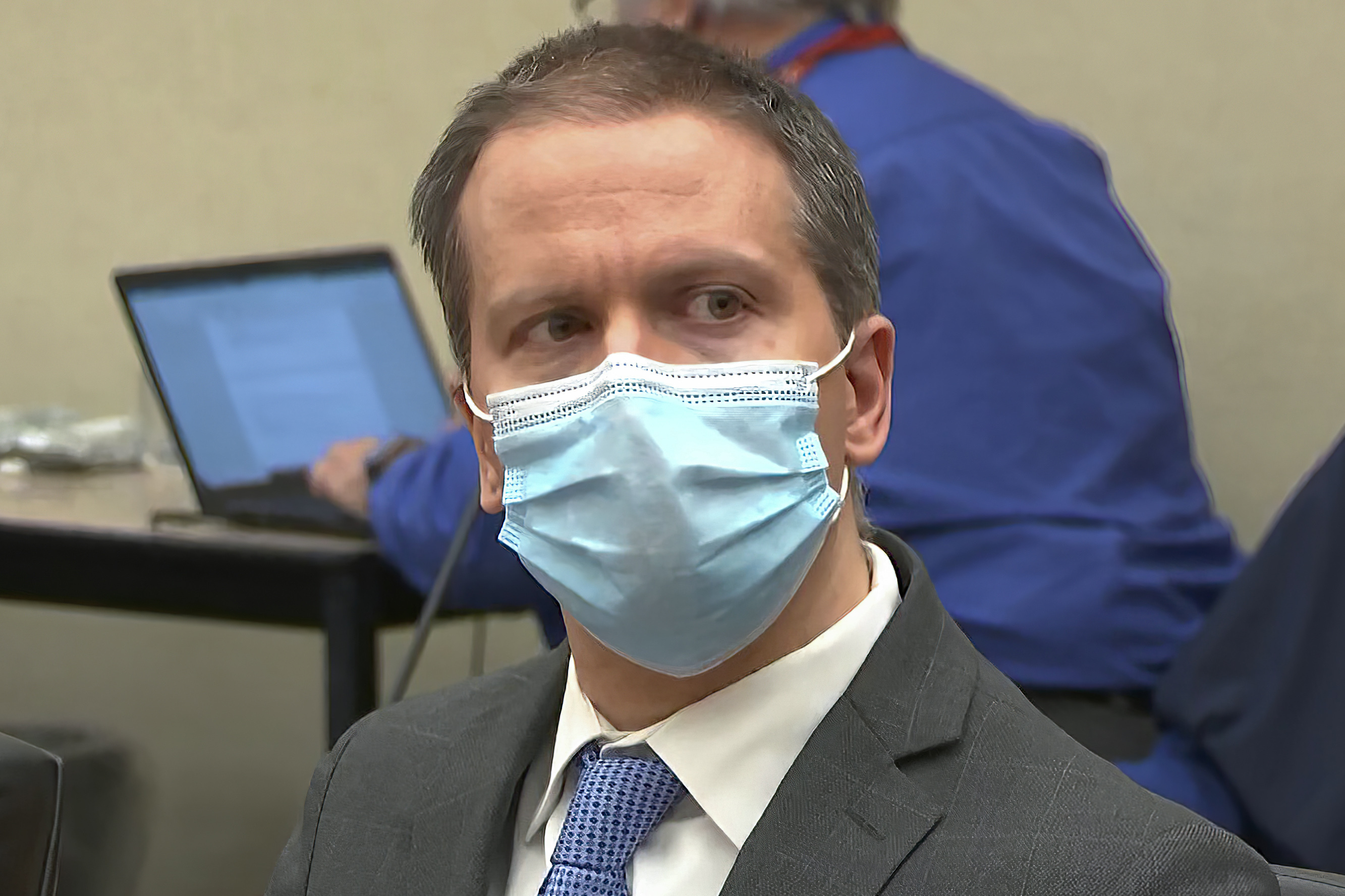

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read