The problem with forgiving Dylann Roof

In the face of mass murder, a stronger, angrier response is justified

When relatives of those gunned down last week in Charleston's Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church expressed forgiveness for the alleged perpetrator, white supremacist Dylann Roof, it was a stunning expression of the capacity of Christian love to overpower the natural urge for vengeance and retribution — and to give spiritual strength to the victims of injustice. Most Americans were deeply moved.

I was among them. But my admiration was mixed with something else — something difficult to describe or justify.

The expression of forgiveness for a murderer who has done nothing to indicate remorse or contrition for an act of unmitigated evil is noble. But nobility is a strange moral concept. It's what we perceive when a person or group deliberately sacrifices its own good — and the more radical the sacrifice, the nobler the act. The soldier who dies saving his platoon is noble. So is a father who sacrifices his own life to save the life of his son. Most noble of all might be God sacrificing his own son — and the son's acceptance of his own sacrifice — to redeem the world. It's most likely this ultimate noble sacrifice — God's act of gratuitous, unmerited love for humanity, which lies at the core of the Christian religion — that inspired the victims of last week's shooting to summon up the strength to offer their own expression of gratuitous, unmerited love for the gunman who took so much from them.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As I said, it's extremely impressive. Undeniably moving. But truth be told, it also left me feeling more than a little frustration at the parishioners who expressed it, and irritation at those many white Christians who praised the victims for refraining from lashing out at the source of their victimhood. Is it really so much less admirable to respond with righteous rage to a deadly assault on one's own good? Is it really so much more commendable to respond to an act of merciless violence with passivity and acceptance?

I was raised as a secular Jew. Though I converted to Christianity as an adult, I continue to admire the unwavering insistence of post-Holocaust Jews that they will never again allow themselves to become victims. That's why, despite my own occasionally searing criticisms of Israeli policy, I remain a committed Zionist — because Zionism is a form of nationalism, and nationalism is one powerful and admirable way for a group of people to protect itself against mortal enemies.

Throughout much of their fraught, wrenching history in the United States, African-Americans have taken a more distinctively Christian approach to their suffering and oppression. In many ways, this has been an enormous benefit — helping slaves to hold on to dignity and hope for freedom in the face of scalding acts of dehumanization, inspiring newly freed blacks to build better lives for themselves in a country still permeated by toxic levels of racism, galvanizing the Civil Rights Movement in its effort, at long last, to secure equal rights for black citizens.

Especially in its embrace of non-violence under the leadership of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the push for civil rights was a profoundly Christian movement that demonstrated the nobility of the African-American cause by placing black suffering and abuse at the hands of white bigots on vivid, wrenching display for all the world to see and judge.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To this day, African-Americans remain overwhelmingly Christian. They also attend church at higher rates, pray to God more frequently, and describe religion as important in their lives more often than the general population. All of which no doubt contributes to the tendency among some members of the African-American community to respond to blatantly racist acts of violence with expressions of Christian forgiveness.

But there has been another, less dominant, less Christian dimension of the black struggle in America, one dominated by nationalism and a willingness to countenance political violence (or at least the threat of political violence) in self-defense. Instead of marching peacefully for justice, equality, and inclusion, as MLK did, men like Martin Delany, Henry McNeal Turner, Marcus Garvey, and Malcolm X have preached black pride and responded to repeated, sustained acts of verbal, physical, and institutional abuse with righteous anger and calls for African-Americans to fight back at every turn against the persistence of white supremacy.

Whenever an act of racial injustice sparks a few days of urban rioting — violence that invariably remains confined to poor, black neighborhoods — a well-meaning white person declares somewhere that such actions are self-destructive. Why do African-Americans keep burning down their own communities? It's a good question.

But so is this: Given the enormous abuses suffered by African-Americans, starting on slave ships and wending on down through the centuries of bondage and lynch mobs to Ferguson and Staten Island and Charleston, why don't we see far more violence directed outward against white America — nationalist violence, political violence?

Imagine for a moment that Jews in America lived as so many African-Americans do: descended from slaves, marinated in a culture of violence in squalid, economically blighted urban ghettos, lacking basic social services (like functional public schools), prey to abusive police officers, with large numbers of young men launched into lifetimes of cyclical incarceration by petty infractions.

Would these Jews respond to the latest assault on their dignity — let's say a slaughter in a synagogue at the hands of a neo-Nazi — with expressions of forgiveness?

Or would they instead begin plotting an American revival of the Irgun — the Zionist paramilitary organization that took up terrorism in Mandate Palestine to force the creation of a secure homeland for the Jewish people?

White America is extraordinarily fortunate that the victims of its gravest injustices have consistently chosen a less confrontational response.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

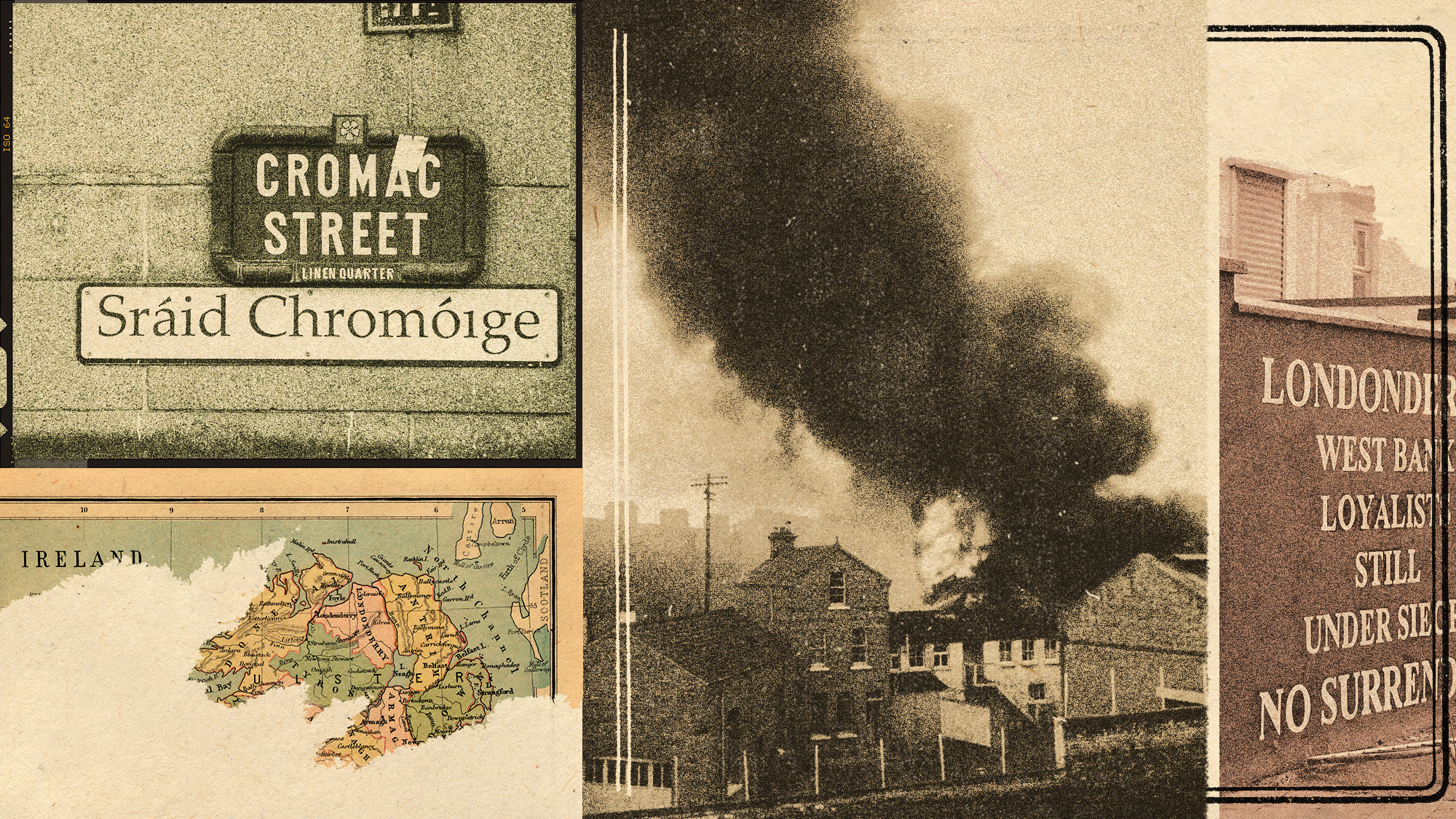

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

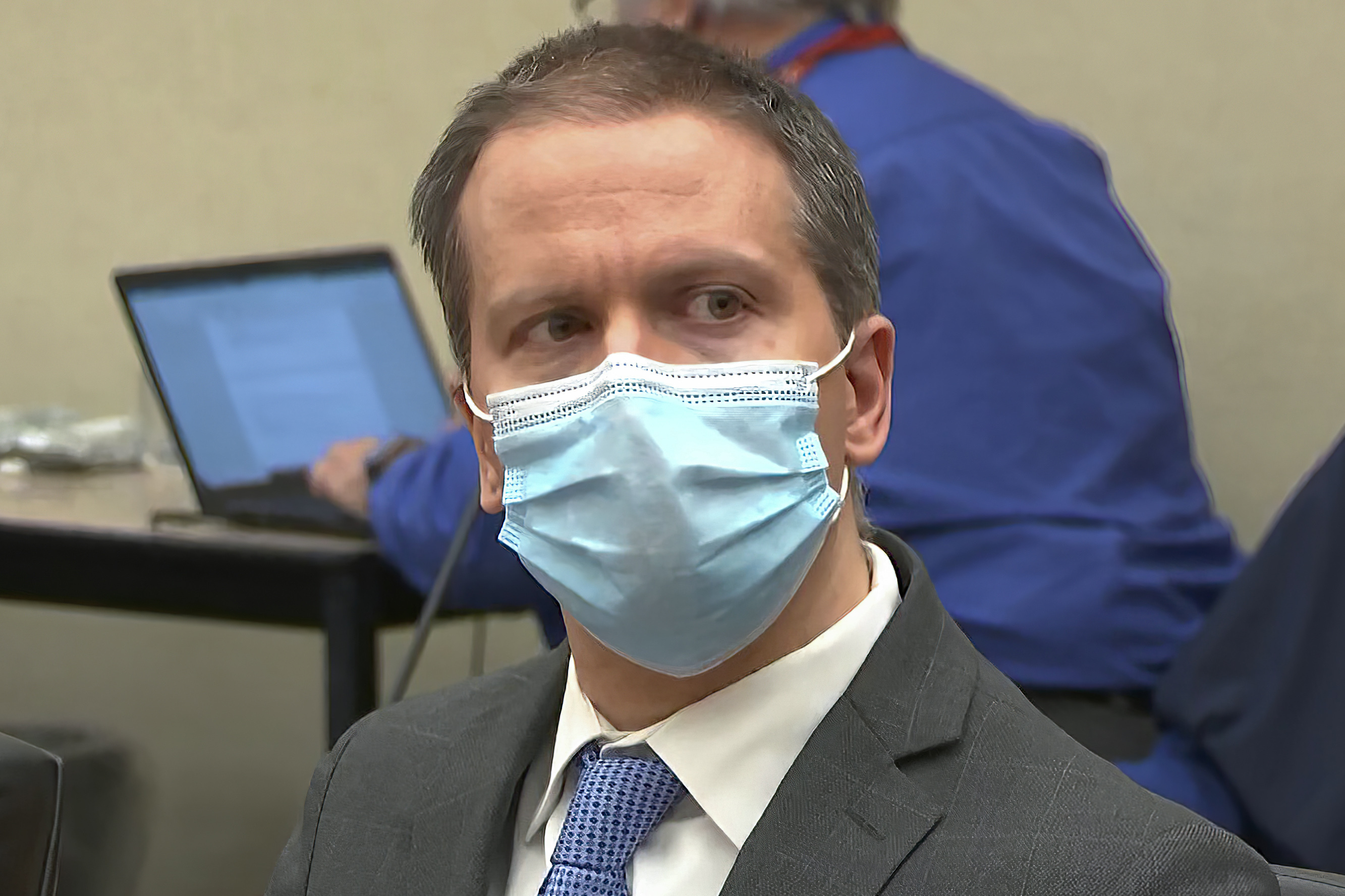

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read