Square's IPO: Is reality finally catching up with Silicon Valley?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Square went public this week, and it had to eat some humble pie in the process.

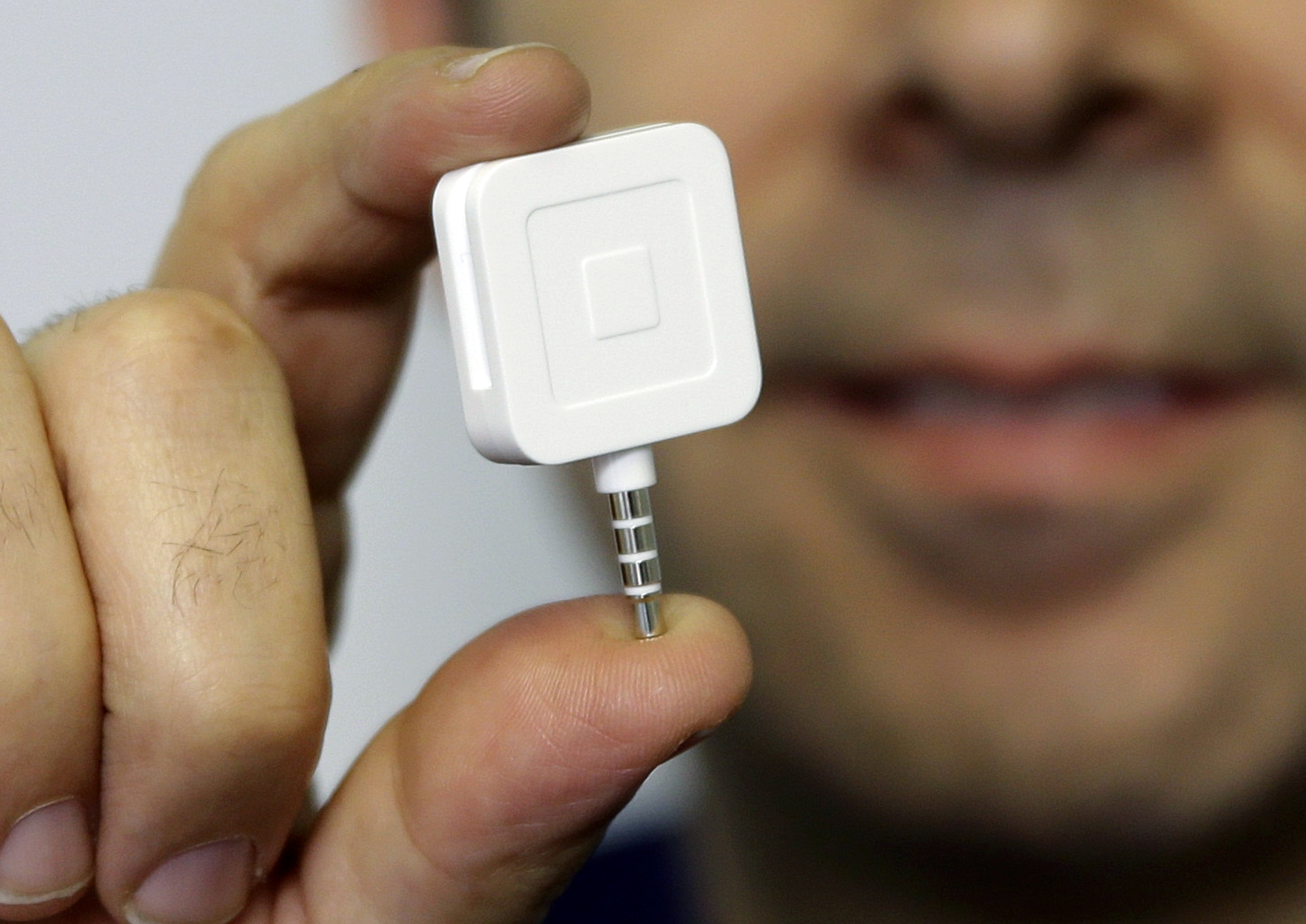

The tech start-up — which, in 2009, introduced food trucks, art vendors and other small businesses to those little square gizmos you can plug into your smartphone and swipe credit cards through — had its initial public offering late Wednesday, selling shares to the public for the first time. It was something of a bust, at least at first: Square's initial filings had suggested shares would go for $11 to $13 a pop, and instead they wound up priced at a measly $9 per share.

Figuring out how to value a private company is a little tricky, since by definition the market hasn't had a chance to process them yet. But the general agreement last year was that Square's private financing put its value around $6 billion. The opening share value established with Square's IPO knocked its valuation down to just $2.9 billion.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That wasn't just a letdown for Square, its shareholders, or even the IPO market in general. It could be the start of a reality check for the entire start-up world. The sector now boasts 143 "unicorns" — private venture capital start-ups valued at over $1 billion. And most of them, including Square, suffer the same problem: It's far from clear how their business models justify those sorts of sky-high valuations.

Now, in Square's case, it has already rebounded. Its share price closed above $13 on Thursday, jacking its market cap up to $4.2 billion. Make of that what you will. But to my eyes the start-up's limp IPO, plus ongoing doubts about its underlying business model, hold illustrative lessons for Silicon Valley.

Around 2 million merchants used Square to process $32.4 billion in payments in 2014. The company makes its money by taking a 2.75 percent cut of every one of those transactions. But it's still credit card companies that provide the networks that make transactions possible: Their service sits at the weird nexus between the banks who issue cards, the merchants and businesses who accept the cards, and the everyday customers who use the cards. Square is piggy-backing on those networks. All it's adding is this little device you plug into your phone to access the credit card companies' existing networks. Square is a middle-man layered on top of a middle-man. So a lot of the revenue from those 2.75 percent slices goes right back out to paying the credit card companies and other financial intermediaries.

On top of that, Square is hardly the only player in this space. Square is facing competition from traditional companies like Visa and American Express, tech darlings like PayPal and Google, and mobile payment apps and readers on offer from Apple, Samsung, and Amazon.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This doesn't mean Square's business model is dead on arrival. But it does mean consistently turning a profit is a challenge. So far, as it turns out, they haven't at all: The company's revenue was $850 million in 2014 — a 54 percent increase over 2013. But it still ended up in the red by $154 million — which was also an increase on its losses the year before. In the first half of 2015, Square brought in $561 million in revenue while suffering $77 million in losses.

Some of this can be justified as a version of the "Amazon" long-game strategy of focusing on expansion, investment, and market share over profits. But there are a lot of self-inflicted wounds here, too. Square tried an ill-fated partnership with Starbucks that wound up being a net loser, and now it's experimenting with a program for advancing capital to various small businesses, along with a host of other gimmicks.

All of which points to an underlying problem that seems to be plaguing Square and the rest of the tech sector: No one is happy with just being a modestly profitable company that offers people a useful good or service. Square's eponymous innovation is a genuinely useful tool for small businesses of all sorts. It's an honorable contribution to our shared economic life, and it still accounts for 95 percent of Square's revenue. But it's not enough to create the massive payouts shareholders present and future are expecting. Capitalists, after all, don't want to be socially useful, they want to make money. Hence the pressure on Square, both external and internal, to keep reaching beyond what its humble business model can sustain.

It's almost inherently contradictory, since the whole idea behind markets is for an innovation to spread once it's been introduced, and then for competition to drive the potential profit that can be earned on it down to as small a fraction as possible.

This is arguably one aspect of a much bigger paradox: Namely, the way public corporations have shifted from being about real economic activity and concrete goods and services, to cannibalizing themselves to spit out the maximum possible payouts for shareholders — and maybe engage in real, concrete economic activity as an afterthought. The logic of it more or less necessitates bigger and bigger payouts, since the flood of money into the financial system has to stay ahead of the deaths of any businesses which get run into the ground. Indeed, the tech sector is arguably cannibalizing itself at a more rapid pace than companies in most other areas of the economy.

In other words, the money hose depends on real economic activity to sustain it, and sooner or later this process bleeds all that activity dry. And that reckoning may be coming for the tech sector sooner rather than later. There's been a surprising lack of those "unicorns" offering IPOs this year — a circumstance a lot of observers chalk up to jittery investors wondering how much longer this can all continue.

Some unicorns can certainly pay off, but it's pretty much a mathematical necessity that most of them can't. And the window of opportunity may already be closing on the (relatively) smaller players like Square. This year's lull means there's a big potential wave among those 143 remaining unicorns to go public next year. The New York Times did some calculations, and even if all those companies wound up with a public valuation that was just one-fourth of their previous private valuations, that would still involve a good deal more money than anyone thinks the IPO market could plausibly throw at them.

It probably won't lead to a recession in the real economy, since we're talking about a pile of money almost exclusively limited to rich investors and other various elite portions of the financial sector. But it will still be interesting to watch. We're either headed for genuinely unprecedented flood of massively successful tech companies, or a lot of wealthy people are going to lose their shirts.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surge

Minnesota's legal system buckles under Trump's ICE surgeIN THE SPOTLIGHT Mass arrests and chaotic administration have pushed Twin Cities courts to the brink as lawyers and judges alike struggle to keep pace with ICE’s activity

-

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire tax

Big-time money squabbles: the conflict over California’s proposed billionaire taxTalking Points Californians worth more than $1.1 billion would pay a one-time 5% tax

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy