Martin Shkreli and how the ruling class loots its own

How a widely loathed pharmaceutical CEO embraced all the worst values of the capitalist elite to the Nth degree, and then inflicted the system's own demons back upon it

The world's self-appointed most eligible bachelor was hiding under a hoodie as police marched him out of his midtown Manhattan apartment tower Thursday morning.

That would be Martin Shkreli, the 32-year-old entrepreneurial enfant terrible who earned widespread public hatred earlier this year when Turing Pharmaceuticals — which Shkreli founded and runs as CEO — acquired a crucial drug that treats a rare parasitic infection and jacked its price up from $13.50 to $750 per pill. After hinting he might drop the price, Shkreli reneged, and later lamented he hadn't hiked it higher.

The arrest wasn't for anything to do with that business, though. It was related to a previous pharmaceutical company he founded and temporarily ran as CEO, which also employed that same less-than-appetizing business strategy of buying the rights to particular drugs and then raising their prices through the roof. Shkreli started that firm, called Retrophin, in 2011 while he was also running a hedge fund called MSMB Capital Management. And according to federal prosecutors, Shkreli essentially used Retrophin as his personal slush fund, raiding its finances to make investors at MSMB whole after the hedge fund began bleeding money.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So one of the most widely loathed men in America is going to be charged with securities fraud. Retrophin booted Shkreli some time ago, and he now faces a civil suit from the company over the same shenanigans. The Securities and Exchange Commission is expected to sue him as well. It's a rare moment of the universe responding to gluttonous capitalist excess with some genuine consequences. But it also reveals on odd complication in the world of the economic elite.

We tend to think of corporations, investors, and CEOs as one monolithic group with the same interlocking interests, which is often true. But public corporations also represent a weird "socialization" of the company structure — where ownership does not lie with the people who run the firm on a day-to-day basis, but rather with a cloud of shareholders scattered throughout society. The CEO and management are hired to work at the behest of shareholders, as the good and faithful steward of their finances.

In fact, if stock ownership — and the stream of capital income it comes with — was actually widely dispersed among everyday American workers, the system's effects would rival the most left-wing populist dreams of Bernie Sanders. But wealth holdings are even more grossly skewed toward the elite than income. Sometimes this produces intra-elite tension, like when a CEO or management turns on investors to loot the corporation they're all a part of. Think of Ken Lay and the Enron disaster, for example. How to prevent this sort of thing is one of the more interesting and under-discussed questions in corporate governance.

Corporate governance is itself a creation of actual government. Our national legislature sets the rules for how corporations are governed, and what the balances of power are. Restructuring that governance can thus reform corporate behavior. Alterations to the rules for lobbying, transparency, disclosure, and how shareholder votes are counted are all worth looking into.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's also the interplay between CEOs and corporate boards, who together form the core management team overseeing most public corporations on shareholders' behalf. In America, this relationship often devolves into a kind of mutual back-scratching society, with CEOs largely able to pick their preferred board members and vice versa, while everyone votes one another enormous pay packages that bleed the company of revenue that could be going to shareholders instead. So while corporations can often seem like a hotbed of intra-elite collusion, they can also be filled with intra-elite tension or even intra-elite fratricide.

This is all at least nominally legal. So how did Shkreli get into trouble?

According to the various legal filings reported by Bloomberg, a trade Shkreli engineered between MSMB and Merrill Lynch in 2011 went horribly south and nearly cleaned the hedge fund out. So Shkreli organized payout schemes with as many as 10 MSMB investors to repay his obligations. He allegedly siphoned money from Retrophin "through fake consulting agreements," "unauthorized appropriations of stock and cash," and by "fraudulently reclassifying a $900,000 equity investment that MSMB made in Retrophin as a loan." He looted some rich people to enrich other rich people. And he did it because he himself was aiming to get even richer than he already was in a particularly free-wheeling sort of way.

Perhaps we can take a certain amount of comfort that the corporate and legal governance systems worked like they're supposed to in this case. That said, things like wage theft regularly go unpunished, while bilking workers out of vastly greater sums. And regardless of whether shareholders and management are fighting or cooperating, both tend to minimize the slice of revenue left over for everyday employees in both cases. In other words, a big part of why the system worked in this case was probably because the victims being looted were other rich people.

But maybe there's at least a rough poetic justice here: Shkreli clawed his way up from a working-class immigrant family to plant his flag on Wall Street, even taking an internship on Jim Cramer's Mad Money. (Naturally.) He embraced all the worst values of the capitalist elite to the Nth degree, and then inflicted the system's own demons back upon it.

How do you like them apples?

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

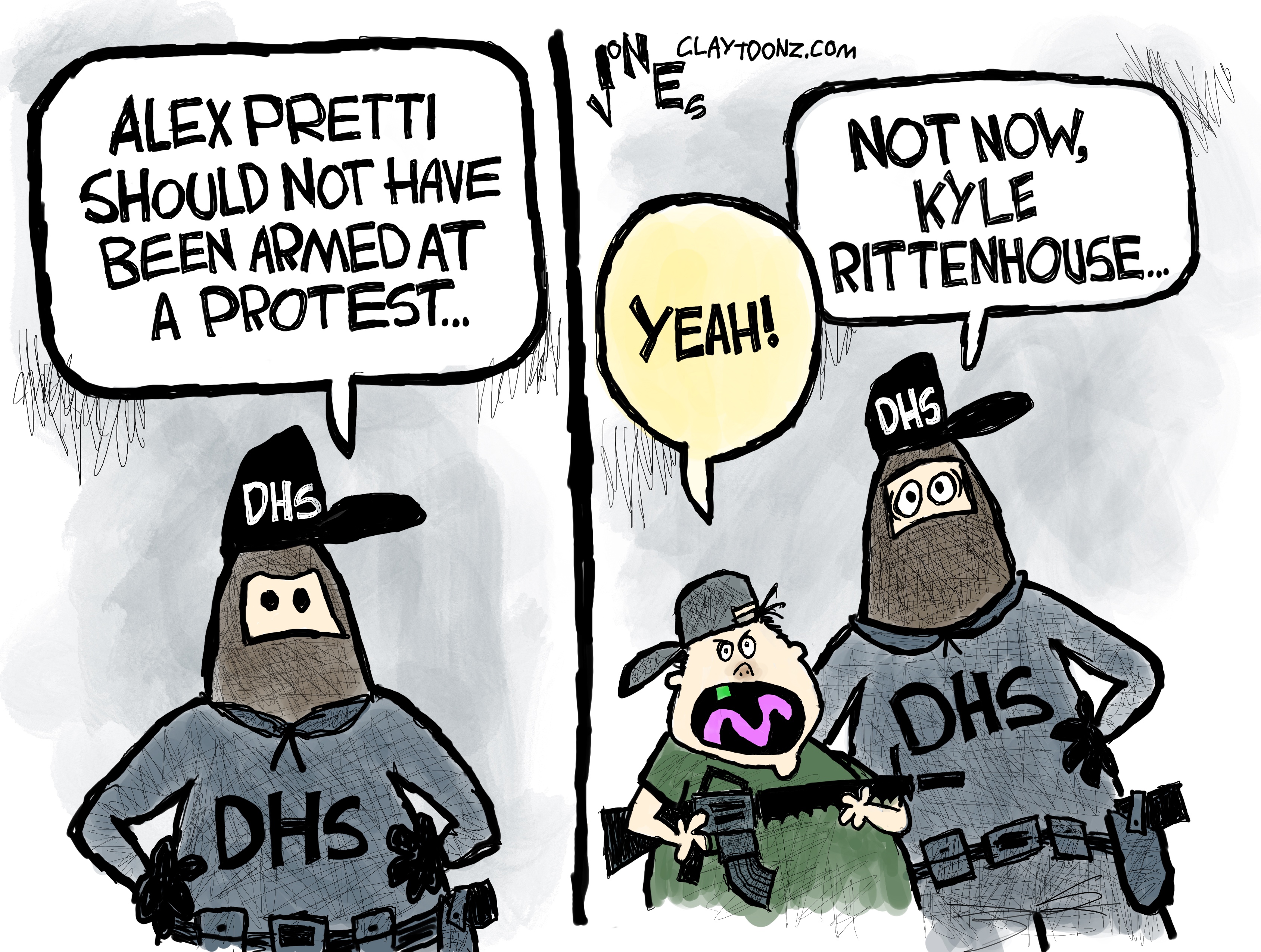

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aid

‘Ghost students’ are stealing millions in student aidIn the Spotlight AI has enabled the scam to spread into community colleges around the country

-

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his health

A running list of everything Donald Trump’s administration, including the president, has said about his healthIn Depth Some in the White House have claimed Trump has near-superhuman abilities

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy