What David Bowie got right about the future of the music industry

It turns out Bowie's capacity for groundbreaking even extended into the arena of economics

David Bowie went down swinging: The shape-shifting musician died this past Sunday, two days after his 69th birthday, which he celebrated by releasing a collaboration with a jazz quintet — his 25th studio album.

And it turns out Bowie's capacity for groundbreaking even extended into the arena of economics. In 1997, he pioneered the idea of using his future royalty payments as backing for financial securities that could be sold on the markets to investors. The so-called "Bowie bonds" themselves didn't work out too well. But the idea of turning the streams of royalty payments from intellectual property rights into a financial security took off in film rights, comic strips, pharmaceuticals, restaurant franchises, and more. Such oddball securities now make up 21 percent of the U.S. market for asset-backed insurance.

But what's even more interesting is why Bowie cooked up this idea. In 2002, in the heyday of Napster and the free file-sharing craze, Bowie told The New York Times he thought the entire business model of the music industry was collapsing.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"I'm fully confident that copyright, for instance, will no longer exist in 10 years, and authorship and intellectual property is in for such a bashing," Bowie explained. "So it's like, just take advantage of these last few years because none of this is ever going to happen again."

"Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity,'' he continued. "You'd better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that's really the only unique situation that's going to be left. It's terribly exciting. But on the other hand it doesn't matter if you think it's exciting or not; it's what's going to happen.''

Fourteen years later, things did not pan out as dramatically as Bowie predicted — but he got the basic thrust right.

The music industry got absolutely creamed by the rise of peer-to-peer file sharing networks like Napster and Kazaa. Between 1999 and 2014, adjusting for inflation, its global revenue dropped by more than half. Here in America, the recording industry did bring a punishing avalanche of lawsuits against both file sharing sites and file sharers themselves, which helped to cut U.S. rates of file sharing in half over the last 10 years. But 20 million Americans still engage in file sharing, versus just 7.7 million who pay for various streaming music subscriptions.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

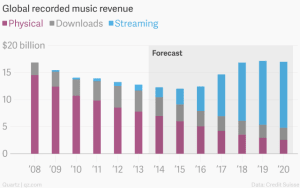

Now, subscriptions aren't the only revenue from streaming. Taylor Swift may protest the idea of Spotify and its ilk giving away music "for free," but they're not actually doing that — it's just that when it comes to "free" streaming, ad agencies, not listeners, are the customers. And the revenue from streaming services is anticipated to increase considerably in the coming years, while sales of physical albums continue to decline. (Though vinyl is making a modest comeback, interestingly enough.)

But even with that in mind, optimistic projections show the industry's revenue will only rebound to around $15 to $20 billion by 2020.

(Graph courtesy of Quartz.)

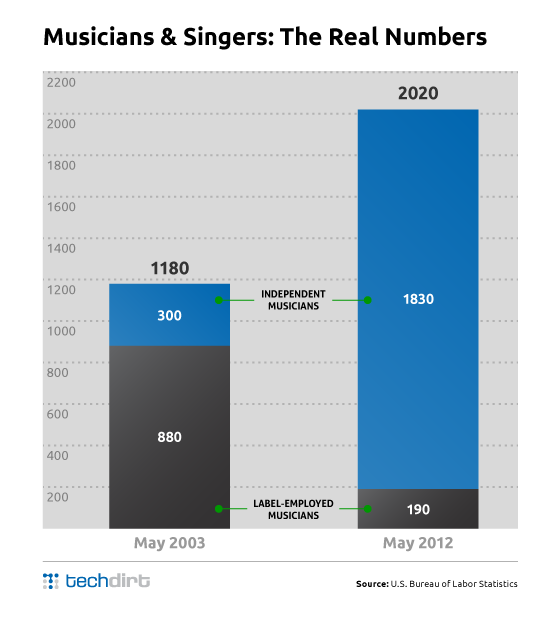

An equally dramatic change is the composition of employment in the recording industry. Between 2003 and 2012, the number of musicians employed by the recording industry collapsed, but the number of independent artists, writers, and performers soared, resulting in a far larger population overall.

It's worth noting that employment in the performing arts — orchestras, symphonies, and the like — also dropped precipitously. But this sector is also often non-profit, and thus relies heavily on public funding for its survival; not the most reliable income stream in the age of austerity.

So Bowie was right to a very large extent. The power of the recording industry, and its reliance on copyright to guarantee its revenue streams, has taken a tremendous beating. But it hasn't gone away. Record labels still effectively call the shots for how the music of all but their most powerful artists is used, and they're the ones striking most of the deals with the streaming services like Spotify. And while a lot more musicians are able to make money from their music, and many more are doing it outside the industry, they're still a very small population — and many of them barely earn enough to make ends meet.

Probably the best way to understand this is that the era in which we shared music via physical mediums like records and CDs was always something of a temporary fluke, technologically and historically. Those physical mediums meant the cost of transferring music from person to person was high, which in turned sustained the music industry's business model. But the era of the physical medium came and went: The industry has been forced to accept digital streaming services, piecemeal purchases of individual songs through platforms like iTunes and Amazon, and other changes in order to ward off the threat of file sharing. This means it costs way less to move music to people, so the industry's revenue collapsed.

Before the age of physical recording mediums, the only way musicians made money was to actually perform for people. We're not going to fully shift back to that state of affairs. But as Bowie pointed out, the economics have moved back to touring as a much bigger part of the income mix for artists themselves.

So you could think of the arrival of the digital age as a massive shift in the relative bargaining power between the industry on one side, and listeners and the new digital platforms on the other. But it didn't shift the bargaining power between the industry and artists, or between listeners and artists, nearly as much. By all accounts, artists are doing at least somewhat better than before. But they're still not doing great.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

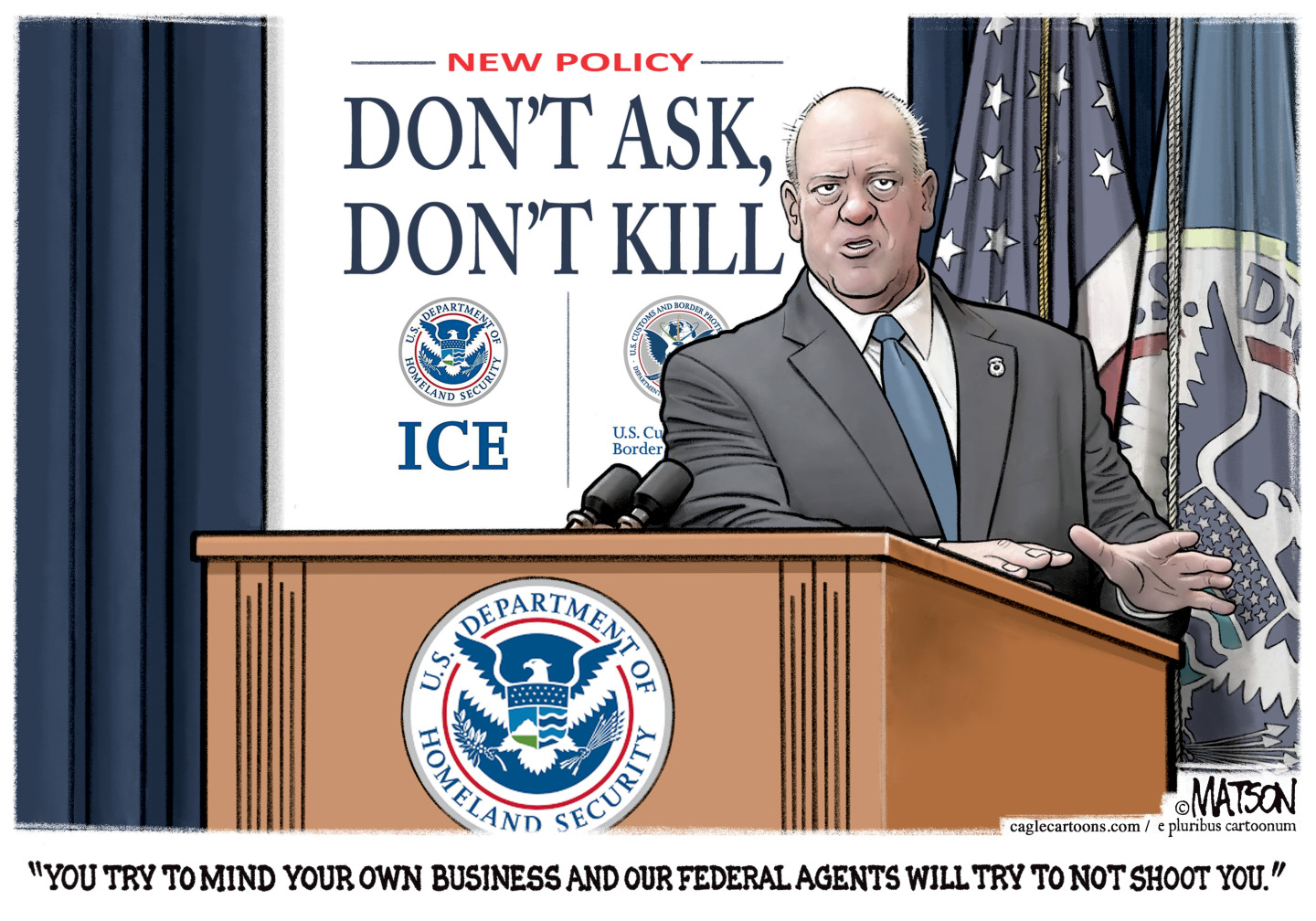

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy