The Federal Reserve is dabbling in wishful thinking

There was a lot of tortured logic in the Fed chair's remarks before Congress

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Does the Federal Reserve's approach to inflation boil down to wishful thinking?

Janet Yellen, who heads up the Fed and the decision-making body within it that votes on monetary policy, made one of her semi-regular appearances before Congress Wednesday. And if you dig through her official testimony, I think it's hard to come to any conclusion other than "yes."

First a quick recap of the Fed's duties: Its dual mandate is to keep inflation low and stable while maximizing employment. It does this by trying to influence interest rates throughout the economy, using a variety of tools at its disposal. When the Fed decides that employment has gone about as high as it can without stoking inflation to worrisome levels, it pushes interest rates up to cool off the economy. Conversely, when employment is sinking or in the doldrums, the Fed can push interest rates down to boost the economy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

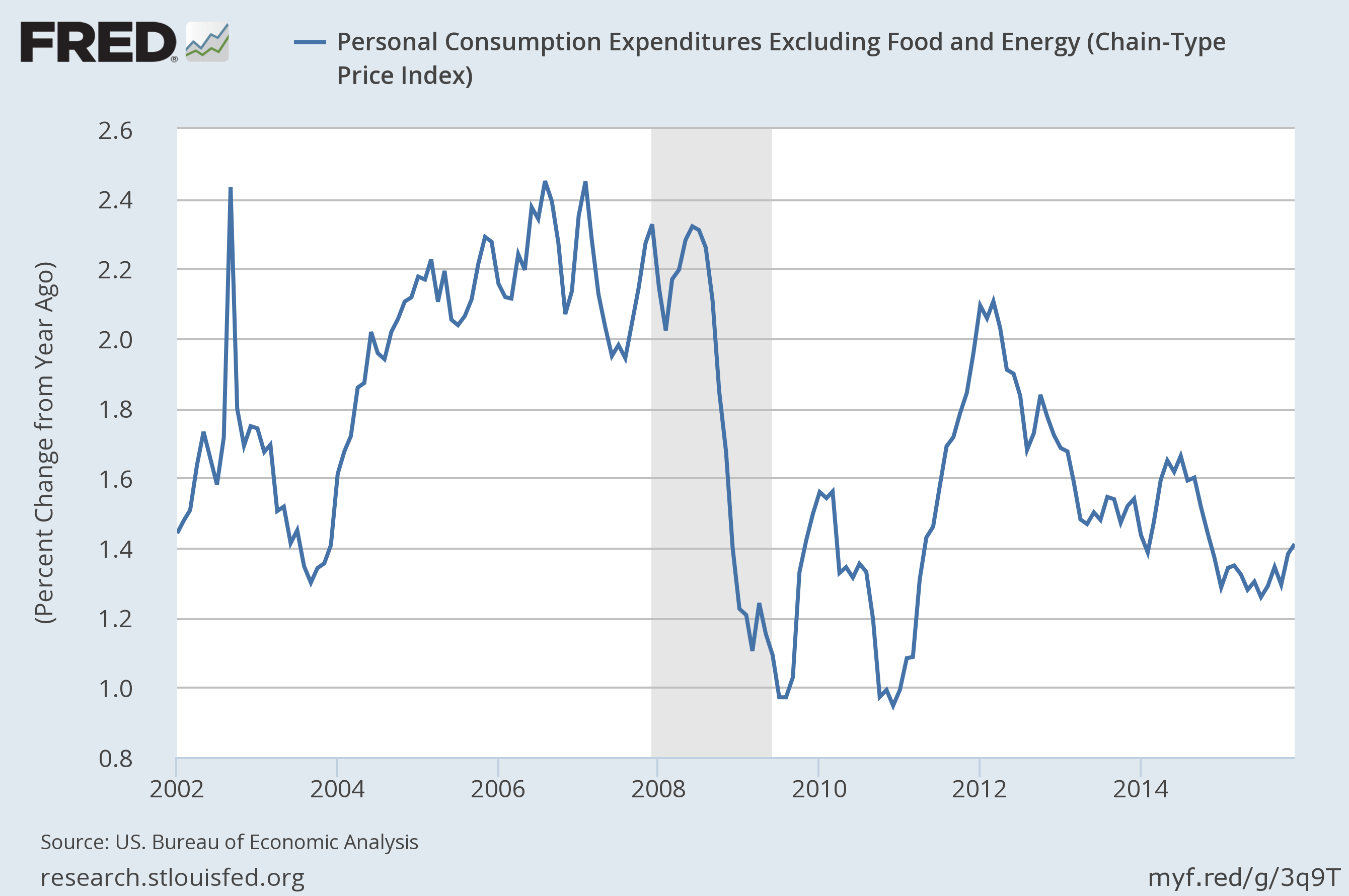

Back in December, the Fed hiked its target interest rate to a range of 0.25 to 0.5 percent. That ended a seven-year run in which the Fed kept its target at rock-bottom — 0 to 0.25 percent — in an effort to help the economy recover from the Great Recession. But it was an odd decision at the time and remains an odd one now. Inflation has chronically failed to hit, or even approach, the Fed's goal of 2 percent. And there's no sign of that changing anytime soon.

This brings us to Yellen's testimony. "Given the recent further declines in the prices of oil and other commodities, as well as the further appreciation of the dollar, the Committee expects inflation to remain low in the near term," she explained. "However, once oil and import prices stop falling, the downward pressure on domestic inflation from those sources should wane, and as the labor market strengthens further, inflation is expected to rise gradually to 2 percent over the medium term." Basically, Fed officials think the forces holding down inflation — the drop in oil prices and cheap imports from abroad — will gradually go away over the next two years.

That in itself is rather optimistic. Oil prices have a huge hole to climb out of, and analysts expect the global supply glut will prevent any serious rise at least through the end of 2016. As for the price of imports, that's largely a China story. The Chinese government has depressed the value of the yuan for years to keep its exports cheap. And even if that weren't happening, China's slumping economy is also putting downward pressure on the value of its currency.

It's certainly possible these situations could ease up in the next two years. But likely?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

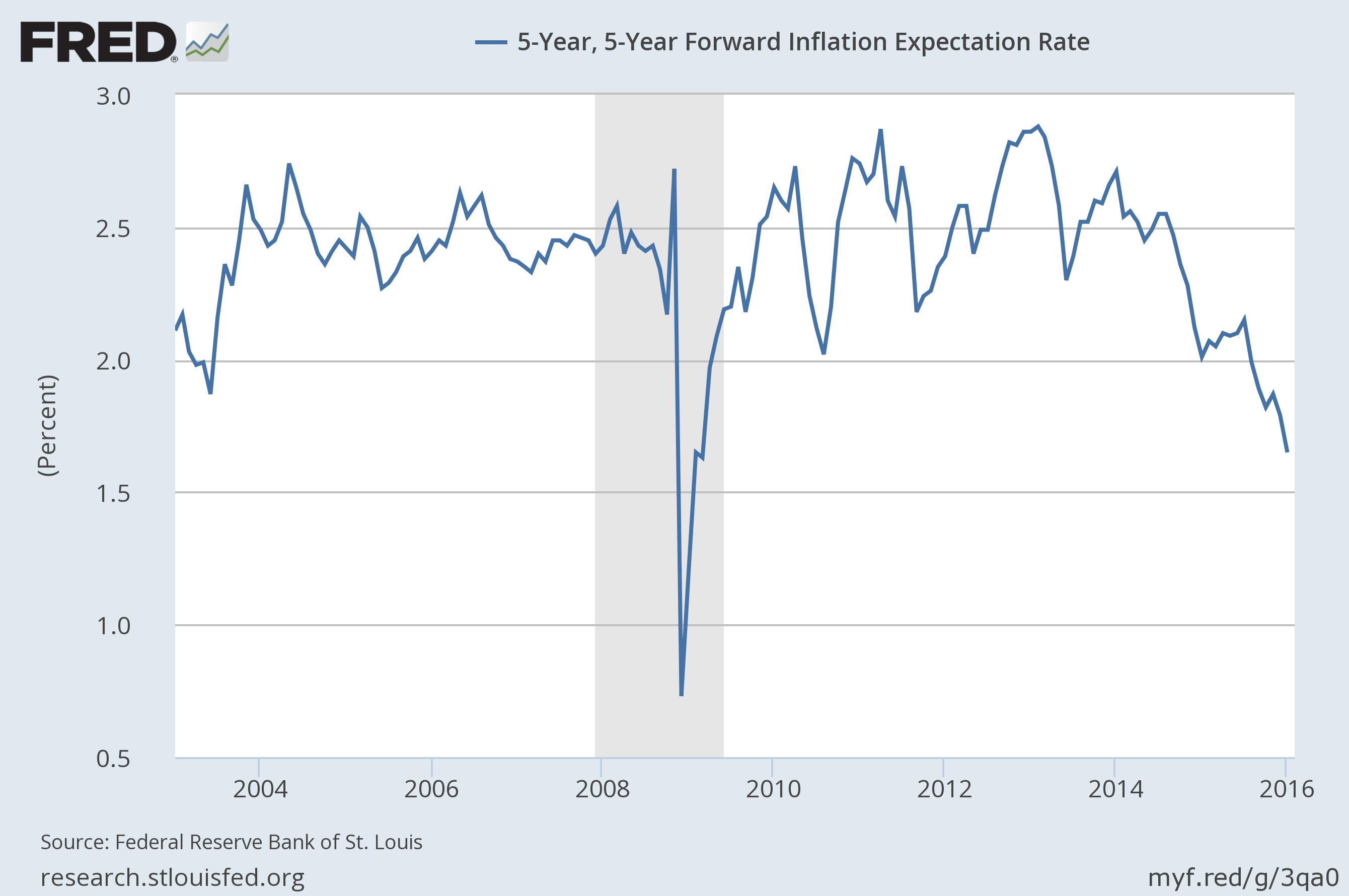

The other big wrinkle is inflation expectations. Basically, how particular financial instruments are traded back and forth in particular markets can give us a snapshot of where thousands of investors think inflation is headed. It's the wisdom of the crowds, in action. Ever since the 2008 collapse, that metric has bounced up and down around an expectation of 2.5 percent inflation in five years time. Then sometime in 2014 it started heading down. And it has kept going down ever since.

So does the Fed know something the markets don't? Yellen suggested as much: "Our analysis suggests that changes in risk and liquidity premiums over the past year and a half contributed significantly to these declines. Some survey measures of longer-run inflation expectations are also at the low end of their recent ranges; overall, however, they have been reasonably stable." Translation: Those markets don't just measure expectations of inflation, they also mix in a few other factors investors worry about. So that can muddy the picture.

But the Fed itself has a less than illustrious track record when it comes to projecting where the economy is going — they've regularly overshot since the Great Recession, often comically so. And if you look at the graphs above, and how inflation behaved in 2015 compared to what the five-year expectations were in 2010, you'll see that the markets have been much more accurate.

Yellen's other point is that "it takes time for monetary policy actions to affect economic conditions." So if the Fed waited and inflation began to rise, "it might have to tighten policy relatively abruptly in the future to keep the economy from overheating and inflation from significantly overshooting its objective." This doesn't make a lot of sense either. The Fed's inflation target may be 2 percent, but the economy has operated at 4 percent inflation quite well in the past, and we're currently around 1.4 percent. If inflation starts rising, the Fed will have plenty of time to act, even adjusting for monetary policy's lag time, before things get bad. What sort of jump in inflation could possibly happen that would justify a rise in interest rates so fast that it seriously damaged the economy?

This would all be a curiosity if it weren't for the fact that the Fed has to hold back employment and wage growth in order to hold back inflation. That means real consequences for real human beings, in an economy where plenty of people are still suffering.

The institutional design of the Fed and its entanglements with the financial industry mean it has a lot of built-in biases towards prioritizing low inflation over high employment. Yellen herself may well be an inflation dove. But it's hard to escape the conclusion that, for the majority of Fed officials, they're hiking interest rates not because hikes are necessary, but because they want them to be necessary.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy