Donald Trump is right to pick a trade war with China. He just has the wrong strategy.

It's time for countervailing currency intervention

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most everyone has been buzzing about the throw down between Donald Trump and Ted Cruz at the latest GOP debate, along with the ongoing nothing burger that is Marco Rubio. But something else happened last week, slightly less dramatic but noteworthy: The Donald came within a hair's breadth of saying something sane on economic matters.

It happened when host Neil Cavuto brought up an article by The New York Times that said Trump would support slapping a 45 percent tariff on goods coming into America from China. Trump said that the Times misquoted him on the scale of the tariff he'd impose. But he went on to defend the general policy.

Railing against the trade imbalance between American and China is one of Trump's signature moves, and a tariff is one way to address that kind of problem: It's a tax levied on imports from a particular country in order to make those imports more expensive domestically. In this case, the idea is to make Chinese goods more expensive, bringing their price into balance with equivalent American goods, thus making Americans more likely to buy the latter.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

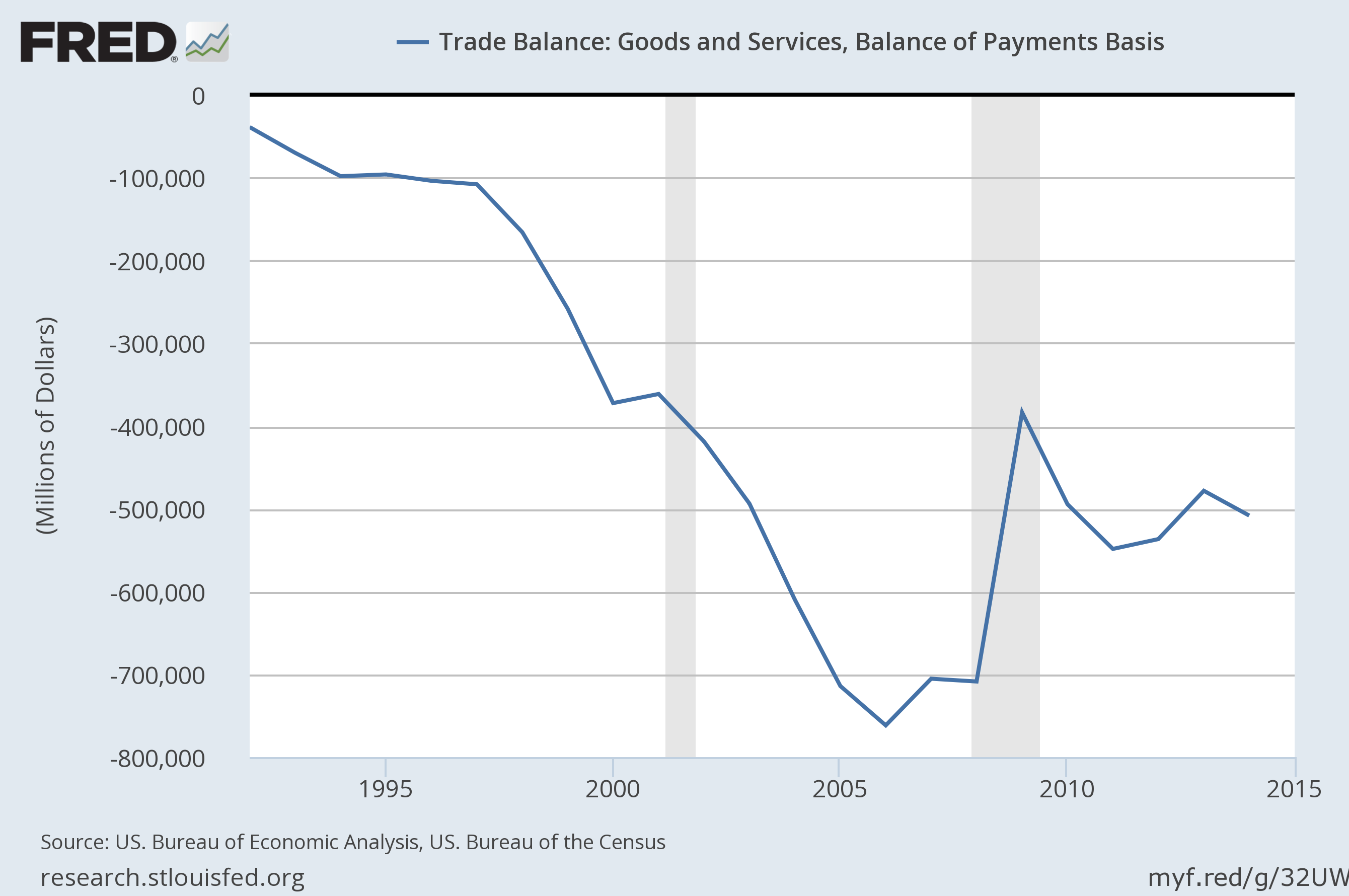

You have to cut through the bluster and sloppiness, but Trump isn't exactly wrong here. The U.S. trade deficit with China was a whopping $342.6 billion in 2014 — not $505 billion as Trump implied, which was America's trade deficit with the rest of the world combined. But that's still a problem. It means China sold $342.6 billion more worth of goods and services to America than America sold to China. That, in turn, means demand generated by Americans isn't producing jobs in America, but in China instead: Back in 2013, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) estimated that we've lost 2.8 million jobs to China since 2001, mainly in manufacturing. This imbalance falls especially hard on the working class, since the jobs that are lost are overwhelmingly held by lower-income Americans.

Where Trump goes awry is in recommending tariffs as a solution. As Robert Scott, EPI's expert on the economics of international trade, explained to me, the basic problem is currency manipulation. The Chinese government is buying up enormous amounts of assets denominated in U.S. dollars. That drives up demand for the dollar, which drives up its value. As a result, the stuff America imports from China becomes cheaper. But the stuff America exports to China becomes more expensive too. On top of that, everything the U.S. exports everywhere else also becomes more expensive compared to equivalent goods and services those countries might buy from China.

"The problem with tariffs is they only affect imports," Scott said. So Trump is "in the right church but he's in the wrong pew when it comes to pushing tariffs. It's the wrong answer to this particular problem." Especially since making American exports cheaper is the key to reviving jobs here at home. Ironically, Trump actually mentioned China's devaluation several times during the debate, but never put two and two together.

Now, China isn't the only currency manipulator in world — but it's certainly the biggest — and there's a long history behind how this started in which the United States is far from innocent. But since currency manipulation by China and others took off in the early 1990s, the annual totals for America's trade deficit have exploded.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In their defense, the Chinese are trying to mend their ways. "They want to be seen as a responsible player," Scott said. "But the truth is China has been doing this for years and their currency is massively undervalued even today."

The fix here, according to Scott, is to go at currency manipulation directly. There were hopes this could be done through the Trans Pacific Partnership. But it was left out of the deal's final language, and China was never a signatory to the pact anyway. Instead, the United States actually already has the legal tools on its books to re-balance the holdings of assets in the two countries' currencies.

"The Treasury and the Federal Reserve have the authority to buy Chinese assets if they're destabilizing our economy," Scott said. "We should be offsetting China's purchases of U.S. assets with our own purchases."

One particular policy proposal is called "countervailing currency intervention." Basically, it's the strategic purchase of assets denominated in the offending country's currency, in the exact amount needed to neutralize the effect of their asset purchases. Since all major economic powers have an interest in everyone behaving when it comes to currency valuations, we could build international cooperation to coordinate the intervention between multiple countries at once. It would still be a "trade war" of a sort, but one that addresses the root of the problem. The immediate goal is to balance out the effects of each country's asset holdings. And the long-term goal is presumably to convince the offending country to draw down its holdings, and then for the U.S. to draw down its own holdings in equal measure as a reward. (Since some people worry rules against currency manipulation can harm a country's ability to do monetary policy, it's worth pointing out that everyone would still be free to buy assets denominated in their own currencies. Which should allow monetary policy to continue.)

One last thing to keep in mind is that the U.S. and China are both guilty of a similar failure here: We haven't done the hard work of building up the ability of our own citizens to supply the demand needed to produce enough jobs internally. That requires making sure job market incomes stay high even for the lowest rungs of society, and that government welfare state programs move enough money down the income ladder to make up for any shortfalls.

In China's case, they made up for their shortfall by devaluing their currency against ours, and thus bringing in demand from American consumers. "China has exported its unemployment problem, principally to the United States," as Scott put it. Here in America, we haven't had a commensurate response, and the result has been rising inequality and a chronic lack of enough jobs to keep everyone employed.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Moltbook: The AI-only social network

Moltbook: The AI-only social networkFeature Bots interact on Moltbook like humans use Reddit

-

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restored

Judge orders Washington slavery exhibit restoredSpeed Read The Trump administration took down displays about slavery at the President’s House Site in Philadelphia

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant U.S. intelligence

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military