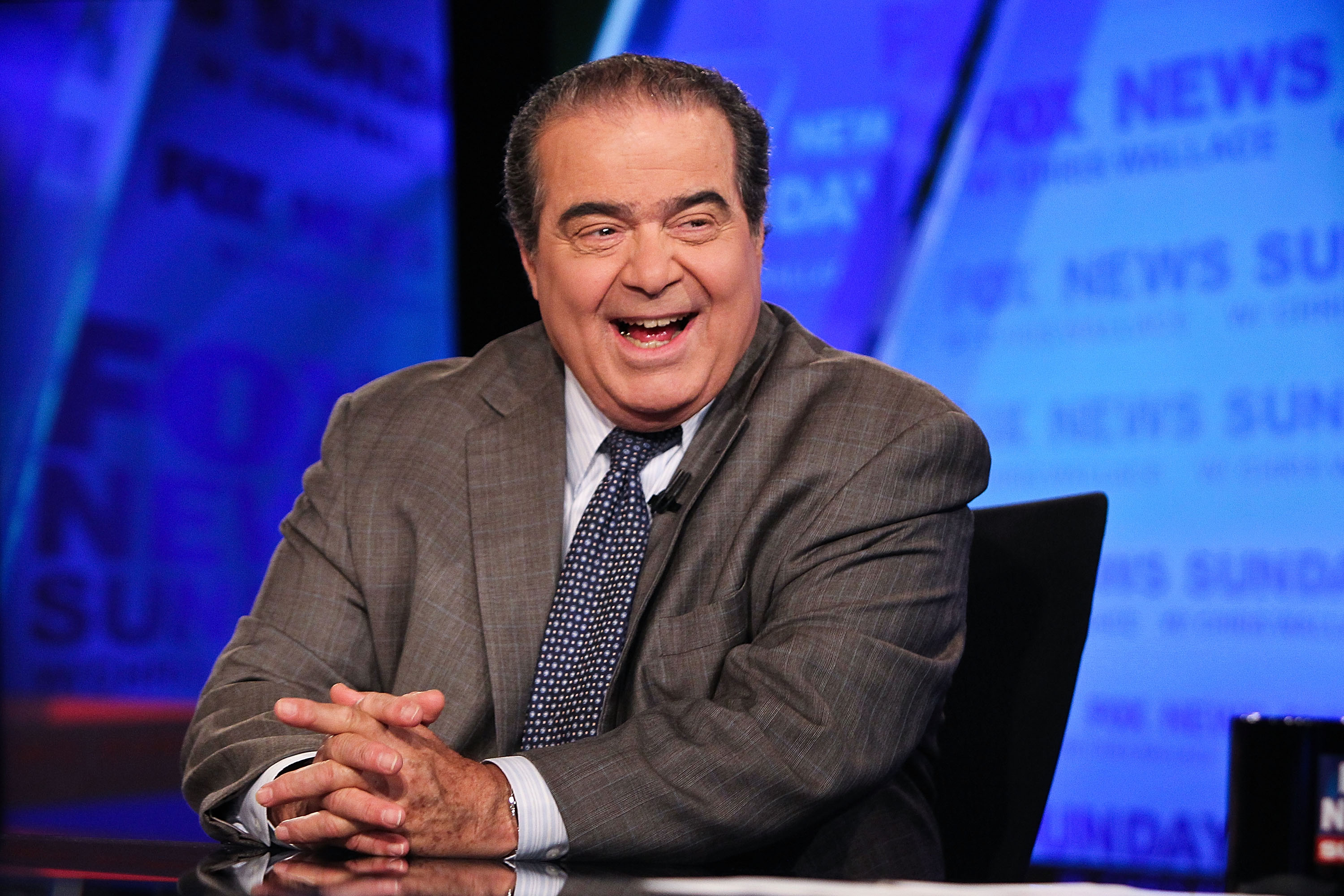

Remembering Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court's gleeful, brilliant combatant

The late Supreme Court justice made conservative legal arguments not just effectively, but with brilliance, wit, and panache

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the exception of Ronald Reagan, conservatives have often been disappointed by their politicians. But they weren't disappointed by one of their non-politicians: Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Indeed, conservatives loved Scalia.

Scalia made conservative legal arguments not just effectively, but with brilliance, wit, and panache. Every Republican presidential candidate who wanted to signal a commitment to appointing conservative judges cited Scalia as the model, the gold standard. That's why there was such an outpouring of grief when Scalia died unexpectedly at age 79 on Saturday.

Scalia frequently defended the Constitution from those who would discard its limits on the federal government while pretending to venerate it as a "living document." He reserved particular scorn for those who saw the Supreme Court's role as that of social engineer.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"If you think aficionados of a living Constitution want to bring you flexibility, think again," he once remarked. "You think the death penalty is a good idea? Persuade your fellow citizens to adopt it. You want a right to abortion? Persuade your fellow citizens and enact it. That's flexibility."

"The irony is that these individuals — predominantly unknown, unaffluent, unorganized — suffer this injustice at the hands of a court fond of thinking itself the champion of the politically impotent," Scalia once thundered.

"A law can be both constitutional and economic folly," was another acute Scalia observation. One observer described this as the quote that best summed up Scalia's whole career on the court.

In dissent, Scalia could be coruscating and mordant, to say nothing of scathing. "Seldom has an opinion of this court rested so obviously upon nothing but the personal views of its members," he once wrote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Dissenting from another high court ruling, he argued, "Today's opinion is an inspiring demonstration of how thoroughly up-to-date and right-thinking we justices are in matters pertaining to the sexes (or as the court would have it, the genders), and how sternly we disapprove the male chauvinist attitudes of our predecessors. The price to be paid for this display — a modest price, surely — is that most of the opinion is quite irrelevant to the case at hand."

Ouch.

When the Supreme Court issued its rulings declaring a constitutional right to same-sex marriage and turning back yet another challenge to ObamaCare, Scalia spoke for conservatives who felt dismayed by the decisions.

"The somersaults of statutory interpretation they have performed ('penalty' means tax, 'further [Medicaid] payments to the State' means only incremental Medicaid payments to the State, 'established by the State' means not established by the State) will be cited by litigants endlessly, to the confusion of honest jurisprudence," he wrote in his King v. Burwell dissent. "And the cases will publish forever the discouraging truth that the Supreme Court of the United States favors some laws over others, and is prepared to do whatever it takes to uphold and assist its favorites."

"The strikingly unrepresentative character of the body voting on today's social upheaval would be irrelevant if they were functioning as judges," Scalia wrote in dissenting from the gay marriage decision he had long anticipated, in which he accused the court of legislating from the bench with evangelicals totally unrepresented. "But of course the justices in today's majority are not voting on that basis."

And yet, Scalia was beloved by his liberal colleagues and adored many of them in return. "My best buddy on the court is Ruth Bader Ginsburg," Scalia said of the woman who is arguably the court's most liberal justice. "Always has been."

Scalia's reign as the court's gleeful combatant coincided with judicial confirmation politics getting much nastier. Amazingly by today's standards, every Democrat in the Senate voted to confirm him in 1986 (the promotion of fellow conservative William Rehnquist to chief justice elicited more opposition). The following year, the Senate rejected Robert Bork's nomination. Five years later, Clarence Thomas was confirmed narrowly after a heated battle.

When George W. Bush nominated John Roberts, half the Democrats in the Senate voted against him, including Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, John Kerry, Harry Reid, and Chuck Schumer. Only four Democrats voted to confirm Samuel Alito, while 25 of them — including Clinton — voted to filibuster his nomination.

It can also be argued that Scalia's tenure went along with the Supreme Court becoming even more of a second legislative body, with members who are unelected and serve life terms. So it is fitting that Senate Republicans are gearing up for a showdown with President Obama over Scalia's seat. Scalia would never have wanted a Democratic president to replace him and his forceful conservatism is one of the reasons both parties began playing hardball on judicial nominees.

Whatever your view of the Senate Republicans' arguments against an Obama nominee to the Supreme Court, it's doubtful they will be articulated as well as Scalia himself would have made them.

W. James Antle III is the politics editor of the Washington Examiner, the former editor of The American Conservative, and author of Devouring Freedom: Can Big Government Ever Be Stopped?.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred