How Bernie Sanders got his foreign policy groove back

Foreign policy used to be Bernie's weak spot. No longer.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Several months ago, the pundit class had a specific and compelling brief against Bernie Sanders: He was wobbly on foreign policy.

It wasn't that he had bad views per se — his vote against the Iraq War is reason enough to rate his judgment higher than Hillary Clinton — rather he was palpably unsure of himself. While he was fluent and confident on domestic policy, he sounded hesitant and poorly-briefed on foreign policy. It was doubly unfortunate as Clinton is far more hawkish than President Obama, leaving a missed opportunity for Sanders to present himself as the defender of Obama's (relatively) non-interventionist legacy.

Fast forward to today, and Sanders has developed a strong foreign policy vision that is actually quite a bit better than I had hoped. This is undoubtedly due to him and his campaign working to fix a weakness, but some credit should also go to the Clinton campaign for helping dredge up some of Sanders' old, good foreign policy views.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The new Sanders can been seen in an interview with MSNBC's Chris Hayes, where he articulates a reasonably comprehensive foreign policy approach. He favors continued action against ISIS, though only with the support of neighboring Muslim nations which have a lot at stake. He's correctly skeptical of Saudi Arabia, arguing their war in Yemen is a misplaced priority at best (true). In keeping with a general pro-diplomacy view, he supports the Iran deal, and while he's suspicious of the country he argues it could be a good foundation for future relations and a relaxation of tensions.

Perhaps best of all, he's not ludicrously biased towards Israel. He was the only major candidate from either party to decline the invitation to speak at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee conference — rather remarkable from the first major Jewish presidential contender, especially given that the crypto-fascist Donald Trump (who has energized anti-Semites across the country) did attend, and his speech was greeted with rapturous applause. Clinton, of course, gave an outlandishly hawkish speech, clearly trying to position herself to Trump's right.

But in a speech Sanders said he would have presented at AIPAC if they had let him present remotely, he affirmed Israel's right to exist, but repeatedly emphasized that the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza — particularly the ongoing expansion of settlements in the former — is unjust, harmful, and a threat to Israel:

Peace will mean ending what amounts to the occupation of Palestinian territory, establishing mutually agreed upon borders, and pulling back settlements in the West Bank, just as Israel did in Gaza — once considered an unthinkable move on Israel’s part. That is why I join much of the international community, including the U.S. State Department and European Union, in voicing my concern that Israel’s recent expropriation of an additional 579 acres of land in the West Bank undermines the peace process and, ultimately, Israeli security as well. [Bernie Sanders]

Very true. The rest of the speech considers the rest of the Middle East flash points in detail, arguing that American power is needed in spots but cannot be used to simply overthrow regimes willy-nilly. We can crush dictators easily, "but it is much more difficult to comprehend the day after that tyrant is removed from power and a political vacuum occurs." That right there has been the single biggest problem with U.S. foreign policy in the 21st century.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Even more impressive, Sanders has spoken frankly about disastrous, largely-forgotten military interventions in Iran, Chile, Guatemala, and Nicaragua that have since come back to haunt us. "I am not a great fan of regime changes," he said at a recent debate. Some of this may be inspired by the Clinton campaign, which attacked Sanders for his 1980s support of the left-wing Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, then fighting against the murderous right-wing Contra militias armed by Reagan. Sanders used to have quite a deep interest in foreign policy, and it turns out his old views were largely correct.

While it's not perfect by any means, taken together this approach puts him somewhat to the left of Obama on foreign policy, and far superior than any other candidate in the race. While Clinton has more experience, she has evinced no sign of having learned from the repeated failure of her preferred military interventions. Insofar as it's possible for the president of a worldwide military hegemon, Bernie Sanders is the candidate of peace and restraint.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

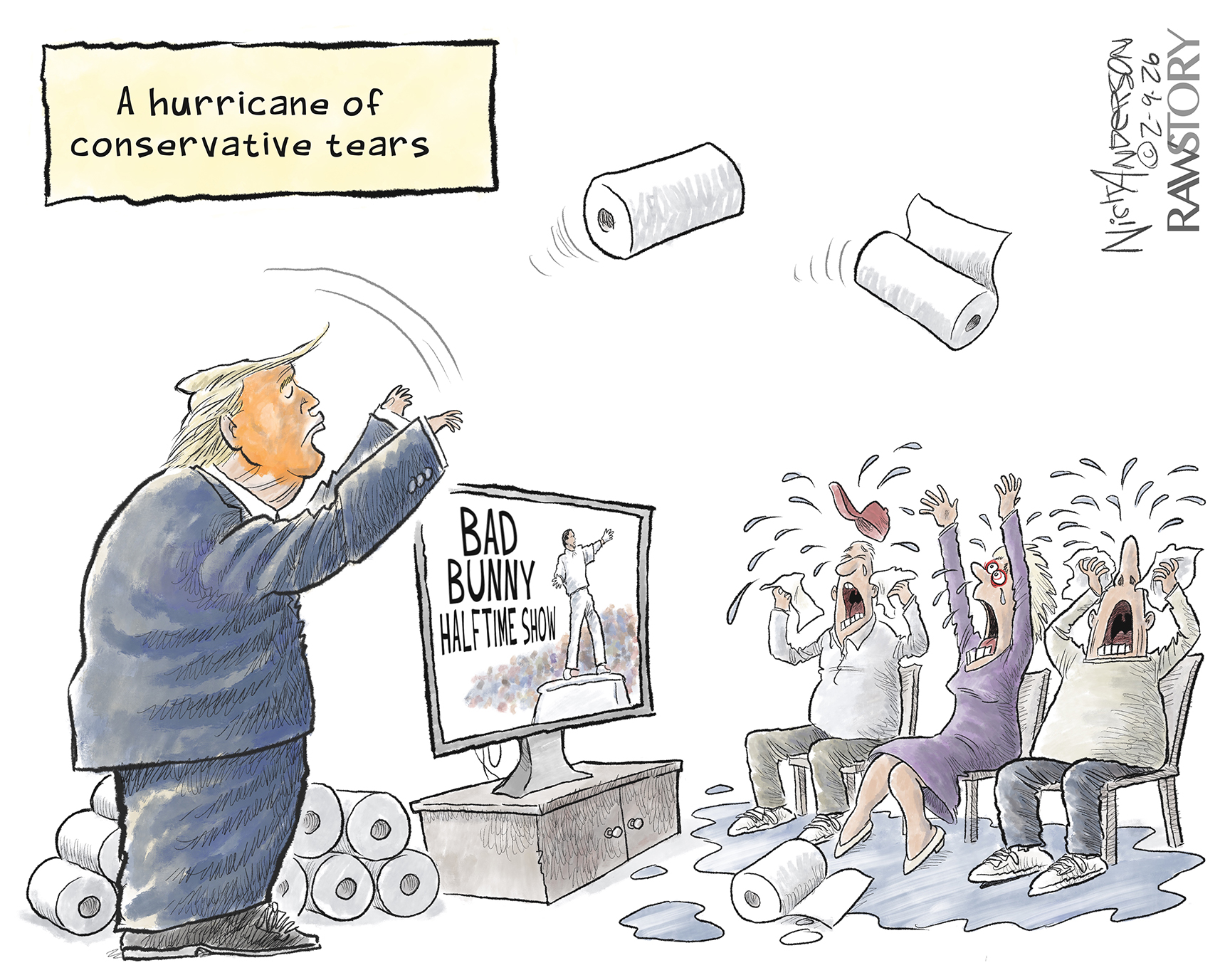

Political cartoons for February 10

Political cartoons for February 10Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include halftime hate, the America First Games, and Cupid's woe

-

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?Today’s Big Question Government requested royal visit to boost trade and ties with Middle East powerhouse, but critics balk at kingdom’s human rights record

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred