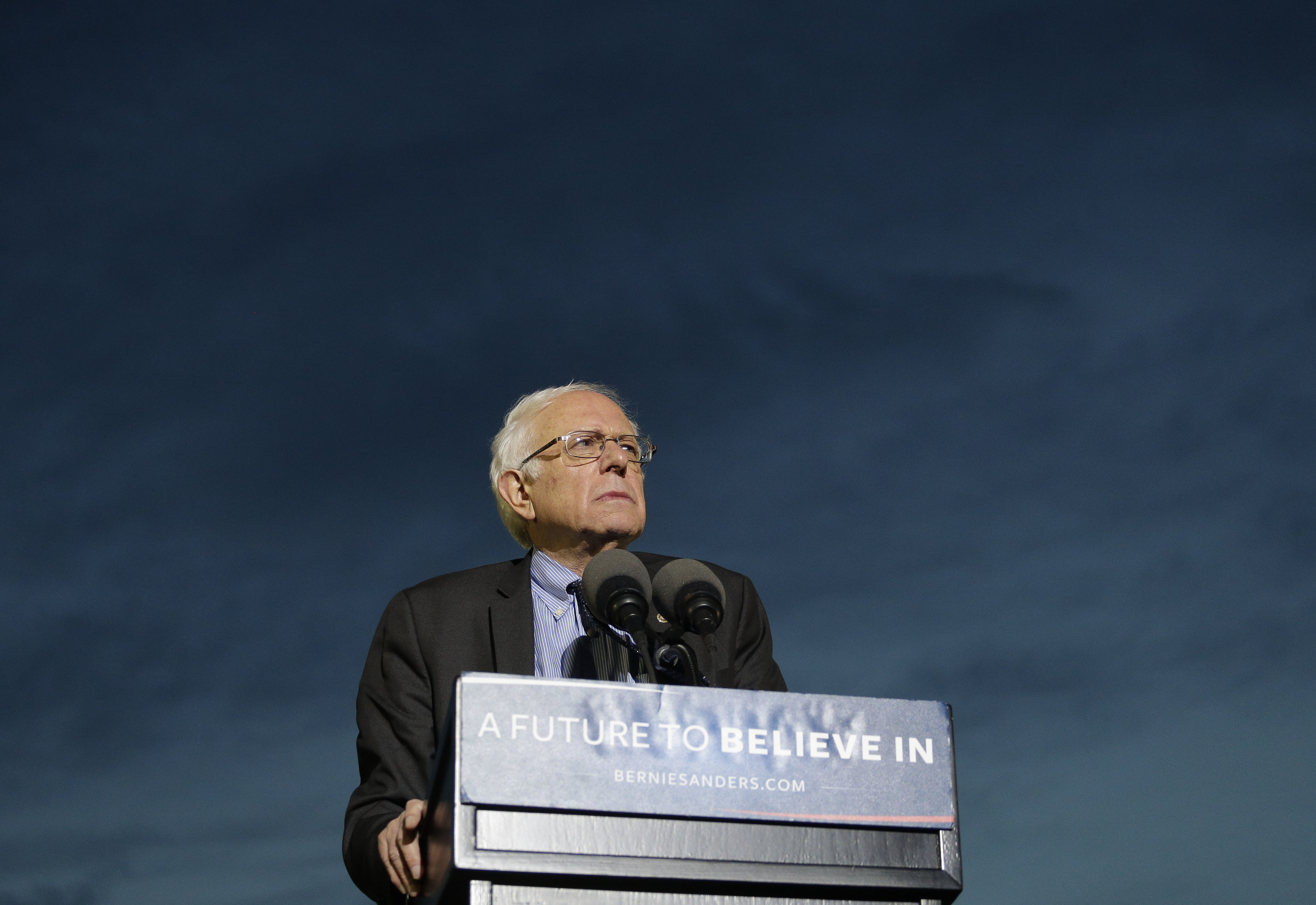

Bernie Sanders' hollow aspirational politics

Sanders doesn't seem to care at all about the unintended consequences of his ideas. That's a problem.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As numerous critics have noted, Bernie Sanders bombed big-time in his recent interview with the editorial board of the New York Daily News. It was so bad, in fact, that it reminded me of Donald Trump.

I know: Sanders' style and some (though not all) of his positions place him poles apart from Trump. But there were disturbing parallels between this interview and the ones the Republican frontrunner has participated in over the past few weeks. At the deepest level, the similarity is this: Both candidates practice the politics of aspiration and express disdain for the politics of practical consequences.

That distinction — a concern with aspiration vs. consequences — parallels in some ways the one that Jonathan Chait has been drawing in recent columns between purity and pragmatism. But they aren't the same.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The categories of purity and pragmatism help to define a candidate's (or a voter's) stance towards her party's governing ideology. Should that ideology be upheld and championed without compromise? Or is it more of an orienting ideal that defines ultimate goals, but from which deviations are acceptable in order to make incremental progress in the right direction? As Chait persuasively argues, Sanders is the obvious purist in the Democratic race for president, while Hillary Clinton is the obvious pragmatist.

On the Republican side, the same distinction abides, though it's also true that pragmatism has gotten such a bad reputation on the right in recent years that leading candidates invariably fetishize purity. The exception in this, as in so much else, is Trump. There's nothing pure about the man. In its place he substitutes a radical flexibility that goes well beyond pragmatism as it's ordinarily understood — and in the process drives mainstream purity-obsessed Republicans batty.

Sanders and Trump fall on opposite ends of the purity-pragmatism spectrum.

But the spectrum separating the politics of aspiration and the politics of practical consequences is different.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The politics of aspiration is all about noble causes, grand gestures, bold stands, sweeping statements of principle. It holds out a vision of political reality very different than the one we inhabit, but it shows no interest in thinking about the details — any details — concerning how we can move from the ignominious present to the glorious future, or how that future will actually work, including what unintended consequences might result from the change.

The politics of practical consequences is, by contrast, devoted to the details of public policy, seeing them as necessary means for making progress toward (as opposed to dreaming idly about) goals. The politics of consequences thinks in terms of taking concrete steps from point A to point Z. It is suspicious of those who refuse to recognize precisely how many steps separate A from Z (insisting, for example, that point Z is really just point D) and of those who prefer to skip over talk of those concrete steps in favor of speaking vividly (but vacuously) about the abiding wonderfulness that awaits us when we (somehow) arrive at point Z, often through some mysterious transformation.

It should be obvious that, for all their substantive and stylistic differences, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are both devoted practitioners of the politics of aspiration.

Trump's ultimate aspiration is to Make America Great Again. Yet he has remarkably little to say about exactly when we were great and what defined our greatness. Neither does he explain when the decline began, what caused it, and how he would enact a reversal of the downward trend.

Things are no better when it comes to specific policy proposals.

Trump wants to deport 11 million undocumented immigrants and build a wall along the southern border. But how will a Trump administration find these illegal immigrants? Will federal agents sweep neighborhoods with high Latino populations, knocking on (or breaking down) doors, demanding that people show papers? Will families by broken up? How would any of this comport with the Bill of Rights? Trump doesn't say.

As for the wall, Trump claims he'll make the Mexican government foot the bill. How will he accomplish this? Will he just charm its elected officials? Make them an offer they can't refuse? Would that deal involve threats and the possibility of armed conflict with our neighbors to the south? Trump doesn't say.

On foreign policy, Trump wants to end both our participation in the "obsolete" North Atlantic Treaty Organization and our support for the international nuclear non-proliferation regime. What are the possible negative geopolitical consequences of these changes? How will he avoid them? Has he even looked into the question? Trump doesn't say.

Over and over again Trump lays out an aspirational vision of the country's future — and displays zero interest in explaining precisely how he will bring it about or what the practical consequences of the changes is likely to be.

Think Sanders is better than this? Think again.

In the Daily News interview, Sanders repeatedly offers his familiar talking points about the dangers of income stratification, the need to break up banks that are "too big to fail," and the importance of punishing those responsible for the financial collapse of 2008. In response, the members of the Daily News editorial board press him for details. And over and over again, he punts.

Sanders wants to break up the banks. Does he think the president or any regulatory arm of the executive branch (the Treasury Department, for instance) has the authority to do that? Under what authority or statute? Could the Federal Reserve do it? How? Should the banks be broken apart into smaller entities? Or will they simply be dissolved? And what about the hundreds of thousands of people employed by these banks? Will they simply be put out of work? Sanders doesn't say.

Sanders also wants to punish those bankers, investors, and others in the financial sector whose actions contributed to the economic meltdown eight years ago. No doubt plenty of Americans share his indignation about wealthy individuals wrecking economic havoc and getting off scot free. But how should they be prosecuted? What laws did they break? Sanders doesn't say.

And so it goes, from Sanders' proposal to make tuition free at public colleges and universities to his comments about the Islamic State and the Israel-Palestinian conflict. In each case, he delivers aspirational rhetoric adapted from his stump speech and dodges requests for specifics, often admitting that he simply doesn't know the answer.

What's distinctive about Sanders is not (or not simply) that he's an ideological purist who refuses to think pragmatically but that he just doesn't know or care very much about the details of how the world works, how to affect concrete change, and what the possible unintended consequences of major changes is likely to be. He'd rather rally the troops and give a rousing speech.

Which makes him a classic aspirational politician.

The great champion of the politics of practical consequences in this cycle, of course, is Hillary Clinton. The great weakness of this style is that it's not very inspiring. Its great strength is knowledge about the complexity of the world and wisdom about the constraints that impinge on the possible.

In the remarkable political success of this cycle's aspirational candidates one senses a frustration with limits and an urge to leap over them and into a whole new, more malleable world. After well over a decade of grinding partisan trench warfare, economic retrenchment, and indecisive outcomes on the world stage, such desires are understandable.

But that doesn't make them reasonable.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question Trial will determine if Meta, YouTube designed addictive products

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred