Why you should never blindly trust the official unemployment rate

As explained by the latest jobs report

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Friday's job report was a study in whiplash.

The unemployment rate dropped a remarkable 0.3 percentage points: It was 5 percent in April, and fell to 4.7 percent in May.

Which sounds great!

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But only 38,000 jobs were created last month. That's absolutely abysmal. It's likely the Verizon strike temporarily eliminated 35,000 to 40,000 jobs in May, which will return now that the strike is over. But even that would've only brought May's count to just under 80,000 new jobs. By comparison, 2015 averaged 221,000 jobs per month, and 2014 averaged 260,000 per month. On top of that, job creation numbers for both March and April were revised down for a total loss of 59,000.

Which is not good at all.

The way to make sense of these two conflicting indicators is to realize the unemployment rate is not always the best indicator of the economy's health. In fact, it's probably a much worse indicator right now than it's been in a long time.

Friday's jobs report actually provides an excellent opportunity to explain why.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's some silly conspiracy-mongering out there about how the unemployment rate isn't the "real" unemployment rate.

But the thing to realize is that the "official" unemployment rate is designed to measure a specific thing, and you can't ask that measurement to tell you more about the economy than it's designed to. The "official" unemployment rate everyone always talks about is actually called the "U-3" rate, and it's the total number of unemployed Americans as a percentage of the labor force.

So what does that mean? The labor force is everyone over the age of 16 who is either employed or has looked for a job within the last four weeks. So a 4.7 percent unemployment rate means 4.7 percent of that population doesn't have a job.

Now let's look at another measure the government tracks: the employment-to-population ratio. This is the percentage of everyone over the age of 16 who has a job. And it held steady: 59.7 percent in April and 59.7 percent in May.

So the percentage of everyone over age 16 who is unemployed held steady. But the percentage of people over 16 who looked for work in the last four weeks and who are unemployed fell. How did that happen? Because some of them stopped looking for work. They left the labor force, not because they found a job, but because they no longer met the criterion.

You can see it in the data that doesn't get the headline treatment: The labor force participation rate itself fell from 62.8 percent to 62.6 percent in May. And the number of unemployed people who stopped looking for work ticked up sharply.

Obviously, that's all bad. But the way the math works, it results in a lower official unemployment rate.

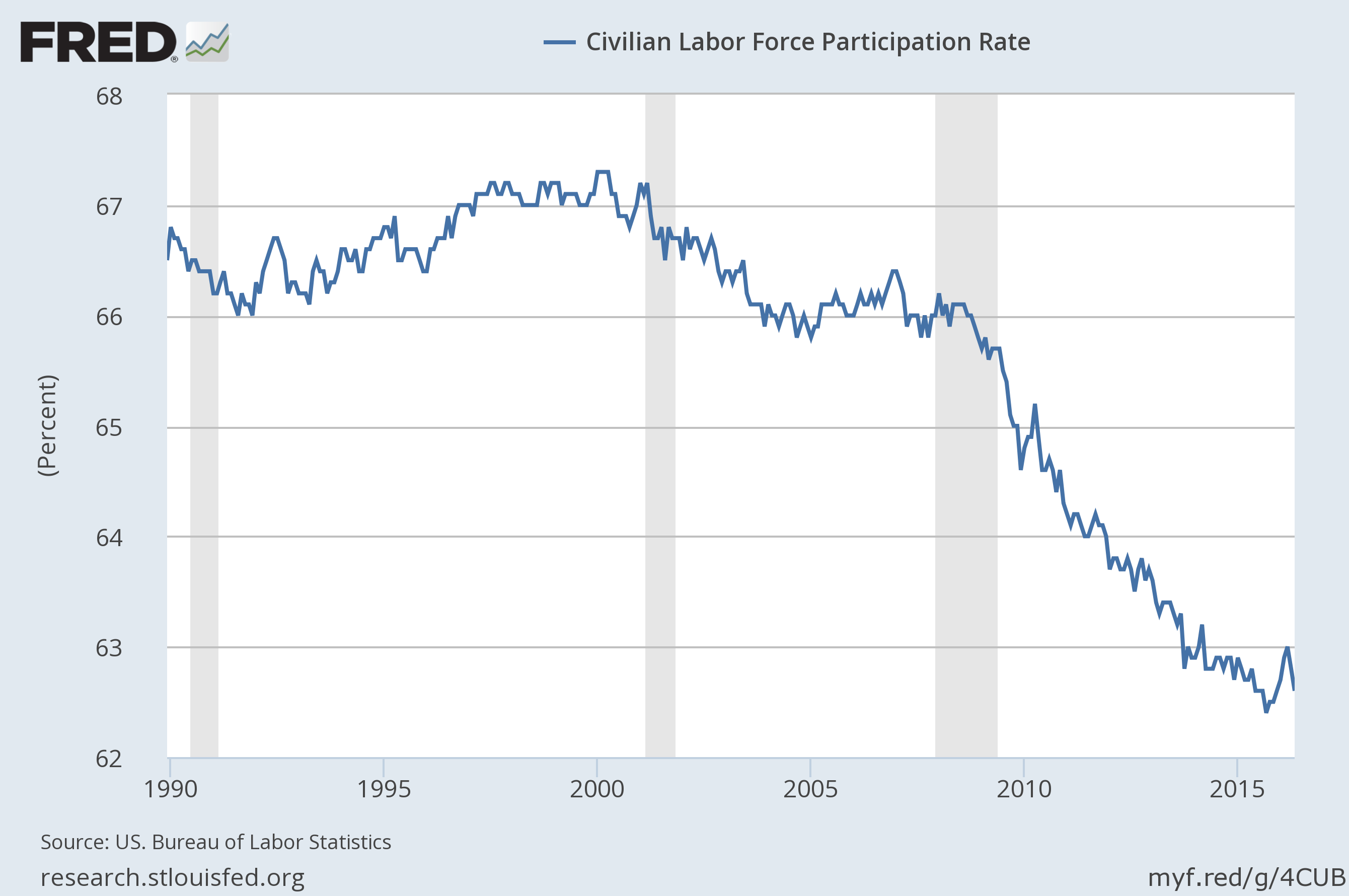

This all gets at a deeper problem. The official unemployment rate is affected by the health of the economy. But the labor force participation rate is affected by it, too. It fell from 67 percent in the late '90s to 66 percent after the 2001 recession and never recovered. Then it fell again after the Great Recession, all the way down to between 62 and 63 percent. It has yet to recover.

It looked like the labor force participation rate might have finally started climbing again, but its fall over the last two months basically wiped out all its gains. The one bit of good news is that its post-Great Recession drop leveled off around the start of 2014, and there's no sign yet it's starting a new fall.

Now, some of that collapse is due to normal demographics changes, in particular old and retired people becoming a bigger share of the overall population. But that doesn't account for all of the collapse. Some of it is people giving up because they just can't find work. That means, until the labor force participation rate recovers by several percentage points, the official unemployment rate simply won't be a good measure of the health of the economy.

"A 5 percent unemployment rate today is a distinctly different indication of labor market slack than a 5 percent unemployment rate would have been before the recession, in 2007," Patrick O'Keefe, director of economic research at the accounting firm CohnReznick, told The New York Times.

So what should we be looking at to judge the health of the economy?

There are actually six different measures of unemployment the government tracks: "U-1" through "U-6." The U-6 rate in particular is worth watching when labor force participation is depressed; it includes unemployed people who look for work less often and people who want to work full-time but can only find part-time jobs, for instance. There's also the employment-to-population ratio for ages 25-54. That is, out of all Americans age 25 to 54, what percentage has jobs? It's helpful because it filters out a lot of the demographic questions — like whether people are retired or students — that bedevils other measures.

But ultimately, the best measure is just the rate at which wages are growing. The economy is at full health when the number of jobs available matches the number of people who want to work. When that happens, workers stop competing for jobs, and employers start competing for workers, which causes wages to rise.

Back at the height of the 1990s boom, wages grew at roughly 4 percent. Right now they're growing at around 2.5 percent.

So we've got the metrics to tell us how well the economy is (or isn't) doing. We just have to be more flexible about which ones we use.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy