Joy Williams' divine comedy

A review of Williams latest book of flash fiction, 99 Stories of God

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

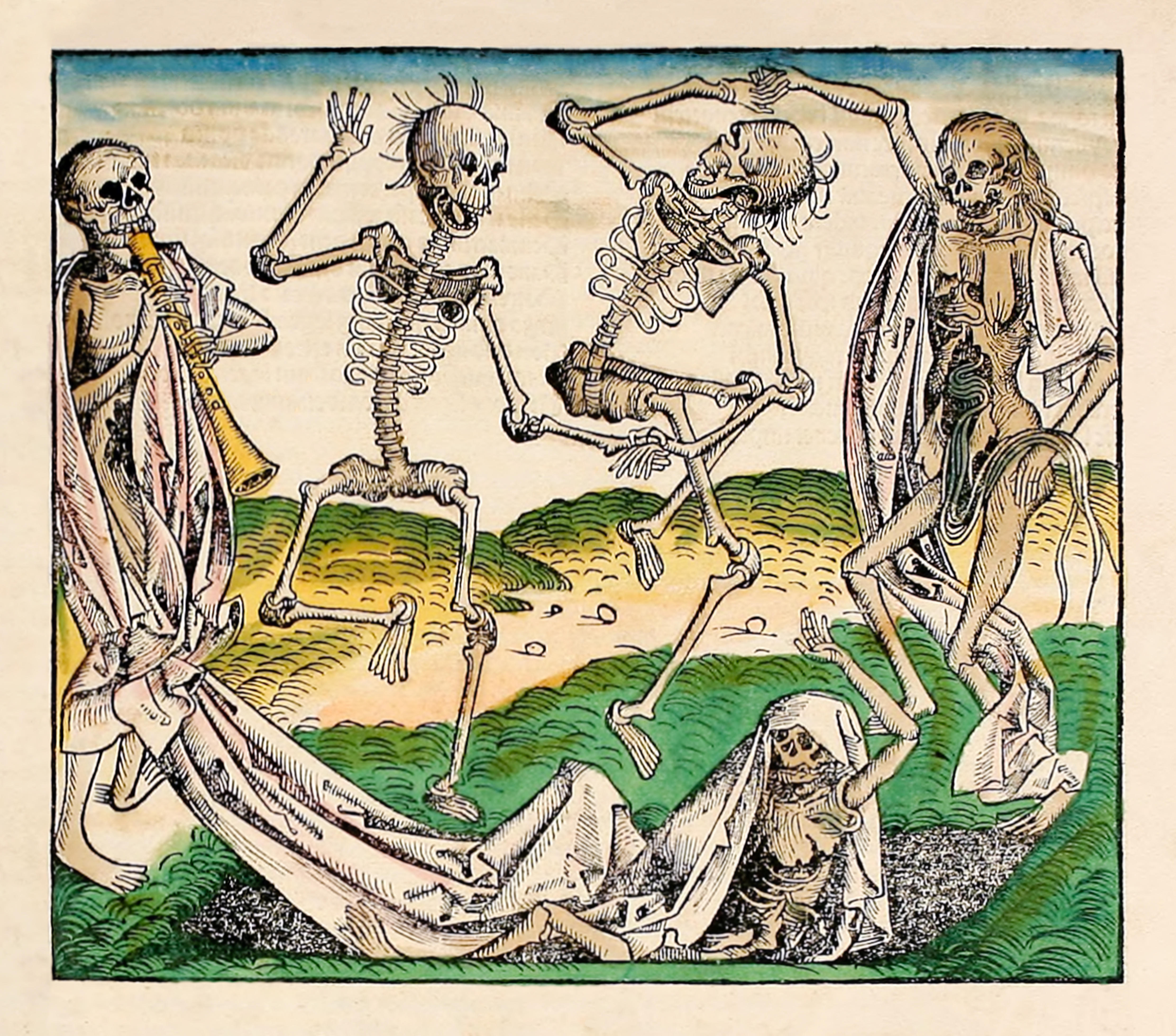

Joy Williams' book of flash fiction, 99 Stories of God — out from Tin House July 12 — is as close as a short story collection gets to a skeleton.

Its 99 component parts are bony and small and matter-of-fact, and while they're certainly related — full of resemblances and symmetries that imply this was once a less compressed whole — whatever connective tissue held everything together is decaying fast. Relics remain: a mother's knees, a child's rabbit-fur muff, a small red book. These things seem more alive somehow than the scholars, married couples with irrelevant children, and writers who people the landscape. These figures wander around Williams' compact experiment in parables thinking they're normal while Williams reduces their situations down to their impossibly acerbic essentials: A child walks with a lion, a dog refuses meat, a woman murders her friend. Then there's God, an unwanted guest among the wolves and wedding guests alike.

It's important that you not get the wrong idea: There's nothing whimsical about Williams, who famously wears sunglasses indoors and out. She studied at Iowa alongside Raymond Carver. Her novels and short stories are as frequently praised for their weirdness as for their greatness. (Her first novel, State of Grace, was nominated for a National Book Award; her second, The Changeling, became a symbol of everything wrong with the avant-garde.) She is also a master of momentum; the stories in 99 Stories of God end and snap, end and snap, their wit yanking you up and dressing you down right when you get a rhythm going.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Williams' God isn't much help to anyone. He makes trite observations about Fourth of July hot-dog eating contests. He tries to get a shingles vaccine from an uncooperative pharmacist. He's dull. Irritating but forgettable, he rarely commands the spotlight even in stories in which he stars. In "70," for instance, he wants to participate in a demolition derby, but the story tires of him and veers instead into the point of view of the pink Wagoneer he plans to drive. (The car turns out to be one of the collection's few believers.)

God doesn't show up at all in a number of stories; vignettes about the Heimlich Maneuver and Ted Kaczynski and elephant executions float by without his input. That seems to be half the point. God turns up when he's unwanted or unrecognized; if formally invited to a gala, he fails to appear. The role of the divine in the architecture of this collection is — to put it mildly — unstable. If in one story we're repressively reminded that God is an abstraction that cannot be known, let alone anthropomorphized, in another he's a comedian rehearsing his act.

The collection grins as a skull might at these reversals; its humor is more a matter of structure than mirth. But there are laughs (with Williams there always are), and in 99 Stories of God, the bulk of those laughs come at the end of each story, when we get a word or two in all-caps that operates as both the punchline and retroactive title of whatever we just read. "70," the story about the pink Wagoneer, is post-titled "DRIVESHAFT".

As with any theologically oriented collection, themes emerge. Some, like, for example, "Doctors Who Drive," are as hilariously unilluminating as they are specific. There's a doctor of veterinary medicine who loves cats too much (he dies, we end with the cat). Another ("50") features a doctor and his wife who start driving and find themselves unexpectedly in Mexico. "The usual questions arose," Williams writes. "Who are we? What have we become? Wherein and why have we been cast? Where to are we hastening?" These questions — fully half the sentences in the story — go unanswered. And while there are echoes here of another story, "20," in which a ferry takes too long, this story is post-titled "Buick Lesabre": The star becomes the car.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I've described two stories already in which a car snatches the focus away from humans and God alike. That's telling, I think. Williams pleasurably undercuts protagonists and the labels they too readily inhabit — particularly those that produce the illusion of authority. God included. She'll specify that someone is a doctor, a "student of literature," a "noted humanist" (or indeed an "inhumanist") mainly in order to prove a job title's utter insufficiency as a descriptor or an identity. That the man in "84" is a poet makes the whole thing only a tiny bit worse. That the antagonist in "79" is a famous writer tells against him, but it's hardly the point.

Williams' contempt for these kinds of reputational sorting mechanisms (and the weight we give them) builds over the course of the collection. This is not a patient text. Take "35:" An artist who "had just won an award and was enjoying a nice midlife bump in her career" is accidentally reported dead and resents her friends for not mourning her enough. The story gets tired of her after two short paragraphs and moves on to her "so-called friend."

If 99 Stories of God hosts a great many people who ossified into their titles, some do get a very mild form of comeuppance. It's a far cry from anything like divine justice; they're usually brought low by some tangential development or impression for which their reputations failed to prepare them. "At the point in his lecture where he was saying that the representative element in a work of art is always irrelevant," Williams writes of the "much-admired artist" featured in "33," "that for one to appreciate a work of art one must bring to it nothing from life, no knowledge of life's affairs and ideas, no familiarity with its emotions and desires, he was seized by the most stupefying boredom and he had to leave the stage."

Still, the collection's miracles are just as correspondingly slight as its punishments: A woman writes to her dead mother and receives a response. A dog refuses to eat ground sirloin her owners considered poisoning. None of these things rise to the level of magic or revelation. Their meaning is small and skilled and up for grabs. "What's significant in this work is not the dogs possessing red colors but that we planted genes into them," says a professor in 51. It seems as good an eschatological guide as any for this strange little volume from Tin House with its four dogs on the cover, tongues out, utterly at sea.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026

Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine solutions - February 27, 2026

-

Magazine printables - February 27, 2026

Magazine printables - February 27, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - February 27, 2026

-

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’

‘The forces he united still shape the Democratic Party’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.