How the Khans went from private grief to national spotlight

Khizr and Ghazala Khan, the Muslim parents of a fallen soldier in Iraq, don't regret criticizing Donald Trump. But the attention has taken a toll.

Six minutes and one second. That was all it took for the 66 years of Khizr Khan's life to become an American moment.

It was not something that he could have anticipated. For years, he and his wife, Ghazala, had lived a rather quiet existence of common obscurity in Charlottesville, Virginia. He was known in circles that dealt with electronic discovery in legal proceedings. Another overlapping sphere was the rotating cast of cadets that passed through the Army ROTC program at the University of Virginia. His wife was a welcoming face to the customers of a local fabric store.

The past dozen years for the Khans had been darkened by their heartbreak over the death of a military son, Humayun, whose body lies in Arlington National Cemetery, his tombstone adorned with an Islamic crescent. Their grief brought them closer to a university and to a young woman in Germany whom their son had loved. It also gave them a conviction and expanded the borders of their lives.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some of their neighbors knew Khan liked to carry a $1 pocket Constitution around with him. In the Khan home, a stack of them always lay at the ready. Guests showed up and they were handed one, in the way other hosts might distribute a party favor. Khan wanted it to stimulate a conversation about liberty, a cherished topic of his. He liked to point out that he lives nearly in the shadow of Monticello, home of one of his heroes, Thomas Jefferson.

And then the Khans stepped into a sports arena in Philadelphia and left as household names. In a passionate speech at the Democratic National Convention, the bespectacled Khan stingingly criticized Donald Trump and his stance on Muslim immigration, scolding him, "You have sacrificed nothing and no one." Quickly enough, both Khans felt the verbal lashings of Trump, the Republican presidential candidate.

And just like that, they found themselves a pivot point in the twisting drama that is American politics.

This is another moment in the lives of Khizr and Ghazala Khan. In 1972, he was studying law at the University of the Punjab in Lahore, the largest public university in his native Pakistan. He was intrigued by Persian literature. Learning of a Persian book reading, he went. Ghazala was the host.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He was raised in Gujranwala in Punjab province, the oldest of 10 children. His parents had a poultry farm. "My life was very ordinary," he said. "I grew up as every other Pakistani. No extra earth-shattering events took place during my lifetime, and we were modest people." But, he said, he had the ambition "to keep moving forward."

The university reading was one thing, but what enchanted him was the host. She was from Faisalabad and was studying the Persian language. He engaged in some decorous maneuvering and decided that she was the woman he wanted to marry. He enlisted the help of his parents, who reached out to her parents. Then the real courtship began.

In 1973, he graduated from law school, and he was licensed with the Punjab bar in 1974. Already, his goal was to move to the U.S. "Everybody's dreams come true if you are able to study and complete higher education abroad," he said.

But he did not have enough money. And so after the Khans were married, they moved to Dubai in the United Arab Emirates. For three years, Khan worked for an American oil field company as the lawyer who handled the affairs of the expatriate workers. Their first two sons were born, Shaharyar and Humayun.

In 1980, the Khans came to the U.S. First, they went to Houston to save up more money. The four of them squeezed into a $200-a-month one-bedroom apartment.

Once he had the savings, he enrolled at Harvard Law School. He graduated in 1986 with a master of laws degree and became a citizen, as did his wife. They moved to Silver Spring, Maryland, and he found work reviewing mortgage documents. It was not his dream job, but a third son, Omer, had been born. Mouths had to be fed.

In time, he moved on to several large law firms, where he specialized in the emerging area of electronic discovery. It involved finding information that was stored electronically to answer discovery requests from opposing sides in lawsuits.

Robert Eisenberg, a consultant who is a pioneer of the field, came to know Khan well and found him highly proficient at his work and immensely likable. "There is an old-world gentility about him," he said. "He has this veneer of formality. But under it is kindness."

And so the Khans settled in, and they became an American life.

There are different vantages from which to understand the Khans' middle son, Humayun, and one of them is through Amir Ali Guerami. He was born in Iran and he went to the same Maryland middle school that Humayun attended. There were few Muslims, and that made Guerami different. And he was very overweight. He was taunted and beaten up.

Humayun would step in. He would walk alongside him, a sentry staring the bullies down, deflecting them. And he intervened when Guerami was being roughed up outside the library. When he was punched in the throat in gym class and could not breathe.

This cemented a friendship that continued throughout high school. Humayun was Guerami's defender and his motivator. He urged him to exercise and to diet. And after his sophomore year, Guerami was 60 pounds lighter.

In his middle son, Khan saw the traits of Ghazala — farsighted and "much more balanced in her thinking and gestures." "I'm a little more emotional and shortsighted," Khan said. Guerami saw this, too. "You always knew he had a plan," Guerami said. "He wasn't just stumbling through life like the rest of us."

A German woman named Irene Auer sat down in a café in the Bavarian town of Amberg, and a man approached her. This was another moment in the life of Humayun Khan.

He was stationed in the barracks at nearby Vilseck. This was 2002. She liked his manner, and she especially liked his English. "He spoke beautiful English and had a very beautiful voice," she said.

They started dating. In time, she began studying international management but stayed with him in his apartment off base on weekends. His mother went to Germany in 2003, and the two became acquainted. In September that year, Auer flew with Capt. Khan to the U.S. to meet his father. This was serious stuff.

As it happened, she opposed the war in Iraq. But he accepted his duty and was proud to be a soldier. "Once he even said to me, 'You know that I am married,'" she said. "I asked him, 'What do you mean you're married?' and he told me, 'Yes, I am married to the U.S. Army.'" On Feb. 9, 2004, he left for Iraq.

They planned to get married the following year and eventually settle in the U.S. His intention was to go to law school. In one of the last emails she received from him, he told her to go pick out an engagement ring.

The Army ROTC center at the University of Virginia is on the first floor of the Astronomy Building. The program is not large — a typical Army cadet class commissions 10 to 20 people. When you walk into the offices, it is the first room on the left. The Khan Room.

There are several pictures of Capt. Khan. Clippings about him. One of his uniforms. Memorial plaques. The piece he wrote for his commissioning. It is where he endures.

A few months after their son's death, the Khans moved to Charlottesville, where their other two sons were living, so they could try to recover as a family. Shaharyar, their oldest son, co-founded a biotech firm that Omer, their youngest son, works at.

The Army ROTC program became a part of their restoration. Tim Leroux, who was the commander from 2009 to 2012 and retired a lieutenant colonel, saw them as the "mom and pop of the department." It became one of their rocks. They attended all its formal events.

At the annual commissioning ceremony, Khan always spoke. When the cadets took the oath, he told them they needed to think hard about their pledge to defend the Constitution, to reflect on what they were pledging to defend, because his son died for that document. And he would give each graduate one of his pocket Constitutions.

Then there would be an award presented, the Khan award, which went to that year's outstanding scholar-soldier.

"For years, I've been telling people he's the most patriotic person I've ever met," Leroux said of the elder Khan. "There are people who will put on cutoffs of the American flag or bumper stickers and say they're patriotic. He has a much more profound idea of being patriotic. It's a complete understanding of what liberty and democracy mean."

Mrs. Khan came to these commissioning ceremonies, too. They were hard for her. Her grief over her son's death reached deep. One day not long after moving to Charlottesville, she stopped at a local fabric store, Les Fabriques. She makes her own clothing and needed fabric.

Carla Quenneville, the store's owner, waited on her. Mrs. Khan told her the story of her son's death. "She said, 'I have to get off my couch and stop crying,'" Quenneville said.

Quenneville wanted to bring sun back into her life. She told her, if she wished, she could spend time in the store, help out if she wanted. And so she did. Pretty much every Monday, she began showing up and assisting customers, giving them tips on the sewing machines that the store sold.

There was other healing to be done. When Auer, the woman Capt. Khan had planned to marry, came to his funeral, Mrs. Khan presented her with his favorite quilt. She asked her to return it when she got married, so they would know she was happy again.

Two years later, Ms. Auer was still adrift. The Khans invited her to stay with them, and she did, from May until August 2006. After returning to Germany, she met a man who became her husband. They have two daughters. She realizes she should return that quilt.

Everything had happened in the space of a week, and it was so much. The Khans were on some dozen news shows in all. All from the dominoes of chance. Months ago, Mr. Khan was quoted in an article in Vocativ, an online publication, criticizing Trump's position on Muslims. When asked about Muslim extremism in the United States, he recounted a conversation with his older son about the need to root out "traitors" among them. Seeing the article, campaign officials for Hillary Clinton wanted to put his son in a video to be shown at the convention, and then asked the Khans if they wished to say a few words. And now all this.

He said recently that he was exhausted from talking to reporters and that it was harming his health.

In recent years, he's gone out on his own as a legal consultant. Now he's taken down the website promoting his law work. He said that he was getting hateful messages and that he was worried about it being hacked. Insinuations were being made that he was involved in shady immigration cases. He said he has had no clients for that sort of work. He said he did commercial law, especially electronic discovery work.

The Khans were one sort of family and now they are another. They have become public figures. People come to them on the street, take selfies with them. They want to be themselves again, mingle with cadets and talk about sewing at the fabric store.

On a recent day, done with a round of interviews in Washington, they stopped at Arlington National Cemetery to visit the grave of their son. Then they went home.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The New York Times. Reprinted with permission.

-

Which way will Trump go on Iran?

Which way will Trump go on Iran?Today’s Big Question Diplomatic talks set to be held in Turkey on Friday, but failure to reach an agreement could have ‘terrible’ global ramifications

-

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deaths

High Court action over Cape Verde tourist deathsThe Explainer Holidaymakers sue TUI after gastric illness outbreaks linked to six British deaths

-

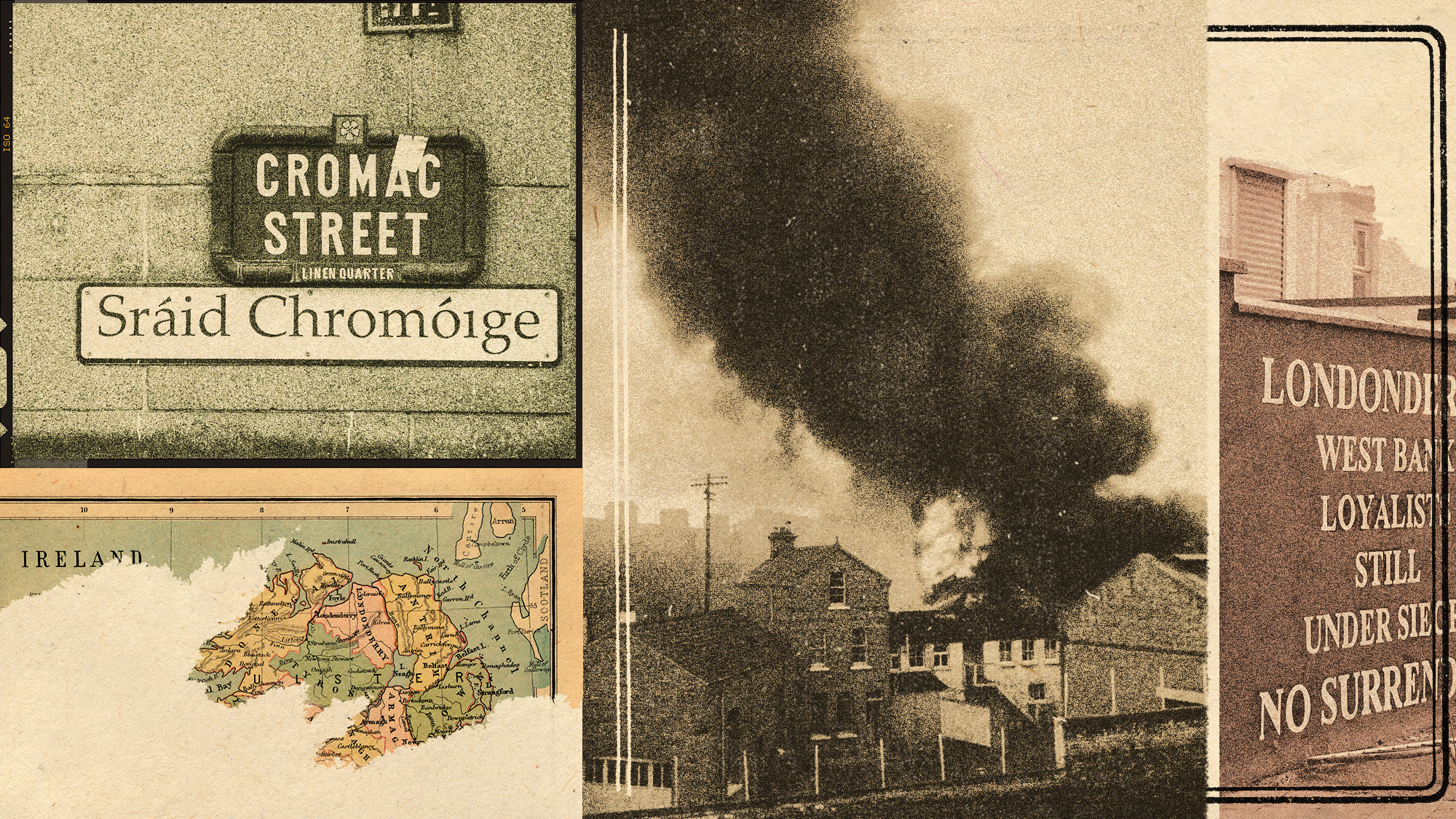

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred