What will happen to Trumpism after Trump?

After Trump loses, Washington will forget about the issues — and voters — he brought to the fore. That's a problem.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

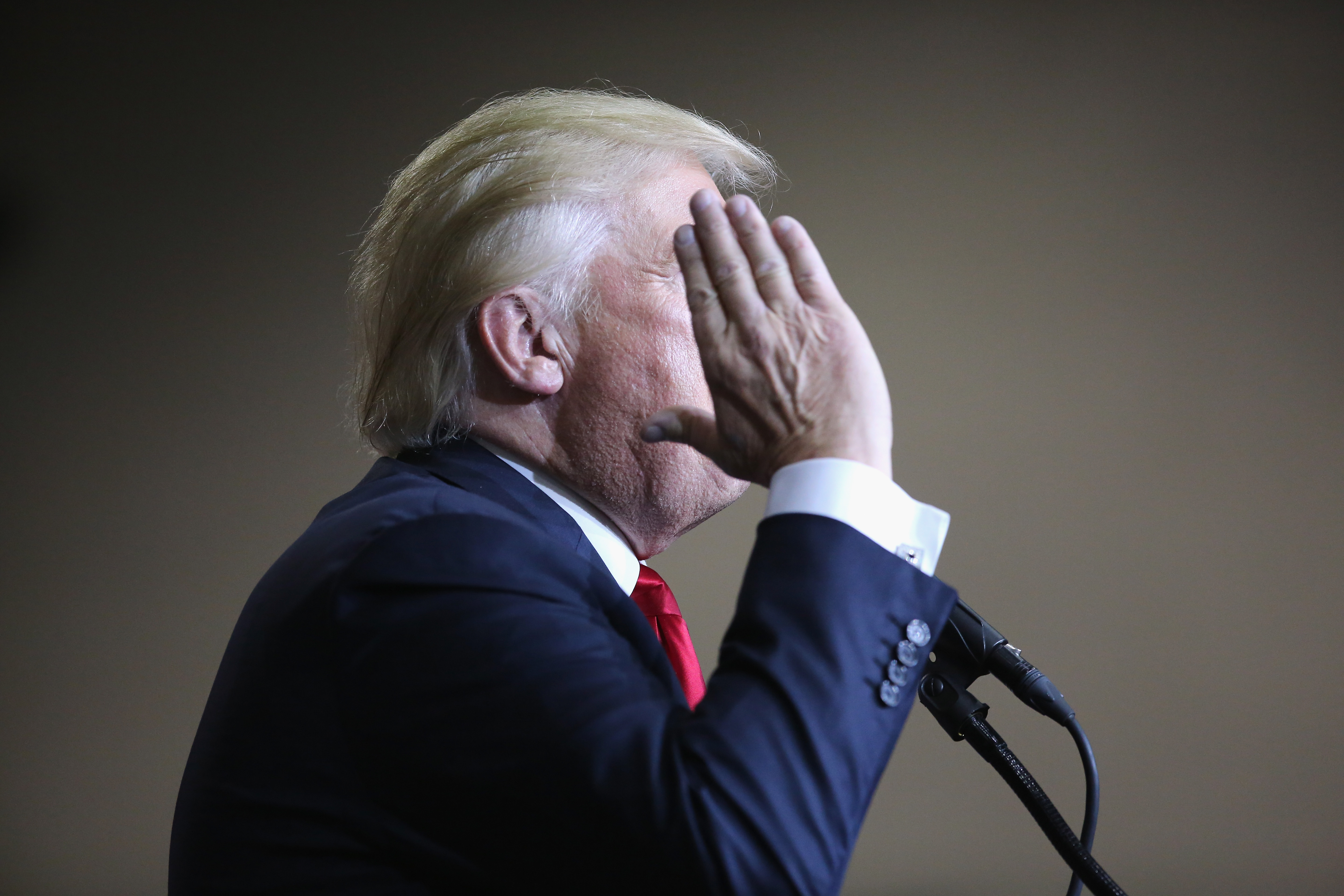

With Donald Trump himself looking forward to a long vacation, it's time to start thinking about a post-Trump era. Some aspects of that not-too-distant future are fairly predictable. Hillary Clinton will claim a mandate to push through Congress whichever elements of her agenda she prioritizes the highest. The GOP, meanwhile, will lick its wounds and then set about planning for a resurgence in the 2018 midterms by making Clinton look as bad as possible.

But what will happen to Trumpism, inasmuch as such a thing exists? What will happen to the issues — and the constituency — that Trump brought to the fore?

I'm increasingly worried about this question, because it's very possible that the answer is: nothing. And that should worry anybody who cares about the stability of the American political system.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Let's start first with the issues. Donald Trump first went from a crank vanity candidate to a real political force by highlighting the issue of immigration. His second pet issue was trade, particularly with China, and its impact on the deindustrialization of America. And shortly after that he added foreign policy, broadly criticizing the establishment of both parties for being too solicitous of allies and clients, and failing to put American interests first.

These are all very real issues. Immigration is probably a more pressing topic in Europe today than in America, but that's mostly because over the past generation immigration has already significantly altered America's demography, while Europe is only at the beginning of such a process. The free-trade consensus has been overwhelmingly dominant since the debate over NAFTA; now the EU is falling apart and new academic research has come out suggesting that integrating China had far more adverse consequences for American manufacturing than originally anticipated, a decline that may, itself, have long-term consequences for the health of the American economy.

As for foreign policy, no less an authority than President Obama himself has expressed increasing criticism of free-riding by allies and of the reflexive interventionism of the Washington foreign policy establishment.

If Donald Trump were a normal candidate, winning the nomination of a major party and disrupting the established political order would force the political system to reckon with his issues. That's what happened when Ronald Reagan won the nomination and the presidency in 1980, putting tax cuts at the center of Republican economic orthodoxy. It's what happened when Ross Perot won 19 percent of the vote as a third-party candidate in 1992, putting deficit reduction front and center for President Clinton's first term.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But Donald Trump is not a normal candidate. And there's a real risk that one consequence of his abnormality will be to tar all of his legitimate issues with his tainted brush.

The Democratic Party has already moved far to the left on immigration, drawing a clear contrast with Trump's GOP rather than seeking the new center. In the wake of a massive Democratic victory, any remaining skepticism will immediately be attacked as warmed-over Trumpism. And on foreign policy, the Democrats have begun to absorb neoconservative talking points along with support from experienced foreign policy hands. There's a real risk that a necessary conversation that liberals should welcome gets squelched because Trump started it.

Even on trade, where Bernie Sanders pushed his party and its nominee somewhat away from neoliberalism and towards a greater concern for protecting American jobs, Democrats will have to reckon increasingly with which side of their bread is buttered. After winning a plurality of college-educated and wealthier whites for the first time in generations, will Democrats really ask globalization's winners to pay so as to protect the livelihoods of globalization's losers?

So what about the GOP? Could it become a party of kindler, gentler Trumpism?

That's what conservative intellectuals Ross Douthat and Reihan Salam recently called for, in so many words. The GOP should admit that the Iraq War was a mistake, and champion a genuinely more restrained foreign policy that defines the national interest more narrowly. It should advocate an approach to immigration that sidelines racial and cultural anxieties in favor of recruiting immigrants that will bring the most benefit and cause the least burden to American citizens, and the least pressure on blue collar wages. And, most radically, the GOP should abandon upper-income tax cuts and the privatization of entitlements in favor of reforms aimed at making our social and health insurance systems more effective, comprehensive, and progressive.

But Trump's heresies on these issues directly conflict with the interests and views of key portions of the party's donor base as well as its most fervent ideological supporters. Moreover, if anything, Douthat and Salam go further; Trump's actual economic agenda looks strikingly like warmed-over Paul Ryan-ism. Kasich, not Trump, was the one making the case for a more reformist tack on domestic issues, as Jon Huntsman did before him. There is no enthusiasm for this approach among either the GOP elite or the rank and file.

And on both immigration and national security issues, a Republican leader looking to embrace a "moderate Trumpist" line would simultaneously have to win the confidence of Trump's voters and fend off attacks — from both the Democrats and from GOP elites — that he or she is a racist, isolationist know-nothing just like Trump. It's much more likely that the next would-be leader of the GOP will focus on winning back traditional Republican voters who defected to Clinton or to Gary Johnson, which will require repudiating Trump and everything he stood for.

So the legitimate issues that Trump has raised are very likely to be frozen out of elite political conversation, at least in the short term. That's a problem in and of itself. But it's a bigger problem because of the constituencies showing Trump the most-vigorous support.

To take the most important example, while foreign policy practitioners overwhelmingly support Clinton, military personnel vastly prefer Trump — and did so during the primaries as well. That partly reflects the partisan lean of the military, but it also likely reflects profound dissatisfaction with the way the military has been used since the end of the Cold War. It's worth noting that Ron Paul also earned disproportionate support from active-duty service members in the 2008 and 2012 election cycles. A political system that refuses to discuss, much less address, the concerns of those who actually fight America's wars, is not a system that will last long.

The same can be said about those voters drawn to Trump for his views on trade or immigration — or merely to the message that their stagnant or declining incomes and the dim prospects for their children are not something they just have to accept as the price of overall progress. It is no answer to say that their problems are actually not more pressing than those of, say, an African-American mother in Baltimore or a teenager fleeing chaos in Central America. Having such a large slice of the citizenry feeling like the political system will not even listen to them is dangerous for the stability of that system.

The only way to avoid a repeating cycle of populist outrage and revolt is for the legitimate concerns of these voters to have a place at the table of one or both of our major political parties. Unfortunately, the peculiarities of Trump's candidacy have made that less rather than more likely. The candidate who ran against political correctness may have made even discussing these topics politically incorrect.

So unless one or both parties choose to go against their short-term political interests to address those concerns, we're going to see another Trump before too long. He won't be kinder or gentler. But he might be more effective.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred