How to make big government agile again

We may hit the next financial crisis before the regulatory response to the last one is fully implemented. Why?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Obama has passed many huge expansions of federal government authority, like ObamaCare and the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, but getting such laws actually implemented was a tremendous struggle. The Volcker Rule, which prohibits certain forms of speculation by commercial banks, took nearly four years to be finalized, and hasn't taken full effect yet — and banks just asked for another five-year grace period before they have to comply. Elsewhere, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission recently delayed regulation of cross-border derivative contracts for an entire year.

We may well hit the next financial crisis before the regulatory response to the last one is fully implemented. Why? Legal scholars finger a culprit called "regulatory ossification," referring to the grinding slowness of today's federal rule-writing apparatus — largely because regulatory agencies are strangled by endless paperwork and frivolous lawsuits.

Fully tackling this problem will probably require congressional action. Luckily, there are many things a president can do to partially alleviate the problem. Since she's looking increasingly likely to take the White House, Hillary Clinton would be well advised to start taking this problem seriously.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

One of the finest pieces of policy journalism ever written is "He Who Makes the Rules," by Haley Sweetland Edwards. It's an in-depth look at the bureaucratic trench warfare that causes the years-long delays in rulemaking. Laws like Dodd-Frank generally don't contain specific regulations saying what must happen; instead they instruct federal agencies to write rules within specific parameters, with the overall process governed by the 1946 Administrative Procedure Act.

Edwards' article goes well with work by Thomas McGarity, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law. In a Duke Law Review article and testimony before Congress, he explains where things went wrong. The APA process was supposed to allow for public comment and participation in rule-writing, while maintaining an efficient federal bureaucracy. But over time, as rule-writing got new requirements for economic justification, environmental impact studies, and the adoption of the legal "hard look doctrine" (making it easier to challenge regulations on procedural grounds), it has become tremendously burdensome for agencies.

Fulfilling those requirements, which require mountains of expert work, "takes an enormous amount of resources," McGarity told The Week. When Republicans control Congress, and hence most agencies are constantly half-starved for funds, it's even harder. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, for example, has been all but hamstrung in the Obama years.

To be sure, many minor rules are written and issued with little fanfare or delay. But ones that affect the operations and profits of big institutions — the ones that really matter — suffer from all-out legal and procedural attacks. That's how some centerpiece parts of Dodd-Frank can be still on hold after over six years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Removing some of these obstacles, like the special regulatory review panel for small business established by Congress in the '90s (that has since been captured by big business) will require new laws be passed.

But the president can do quite a lot. Many requirements for onerous studies could be repealed by executive orders, says McGarity. More importantly, key positions overseeing the regulatory bureaucracy could be filled by someone sympathetic to the agency perspective, rather than the industries they regulate.

President Obama did an abysmal job of this during his first term, appointing economist Cass Sunstein as the chief of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which oversees the regulatory apparatus. The administration did issue many important rules during his tenure, but it also spent a vastly disproportionate amount of time meeting with industry representatives, and effectively slow-walked many critical regulations — particularly EPA ones. For someone concerned with timely action on big finance or climate change, Sunstein was a manifest failure.

At root, this is an ideological problem. Sunstein is a 1970s neoliberal who thinks that regulation is usually an economic drag, and should only be implemented after you prove in 19 different ways that it won't be an undue burden. And four years out of government, he's still peddling proposals for cutting "red tape" which involve forcing agencies to carry out even more expensive, complex studies, and writing into law other requirements that are currently executive orders — making the problem worse.

As Elizabeth Warren pointed out in a recent speech, what is needed is someone with the opposite view — that regulations are a huge net benefit that are absolutely critical to protecting the American economy and citizenry. Slow-walking regulation of finance or climate change with onerous cost-benefit nitpicking when Wall Street just obliterated the economy and American cities are suffering clockwork weather disasters is completely idiotic.

So given that Republicans stand a good chance of hanging onto Congress, if Hillary Clinton wants to achieve anything during her presidency, appointing people who believe in quality government to key regulatory posts might be the single smartest and easiest step she could take.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

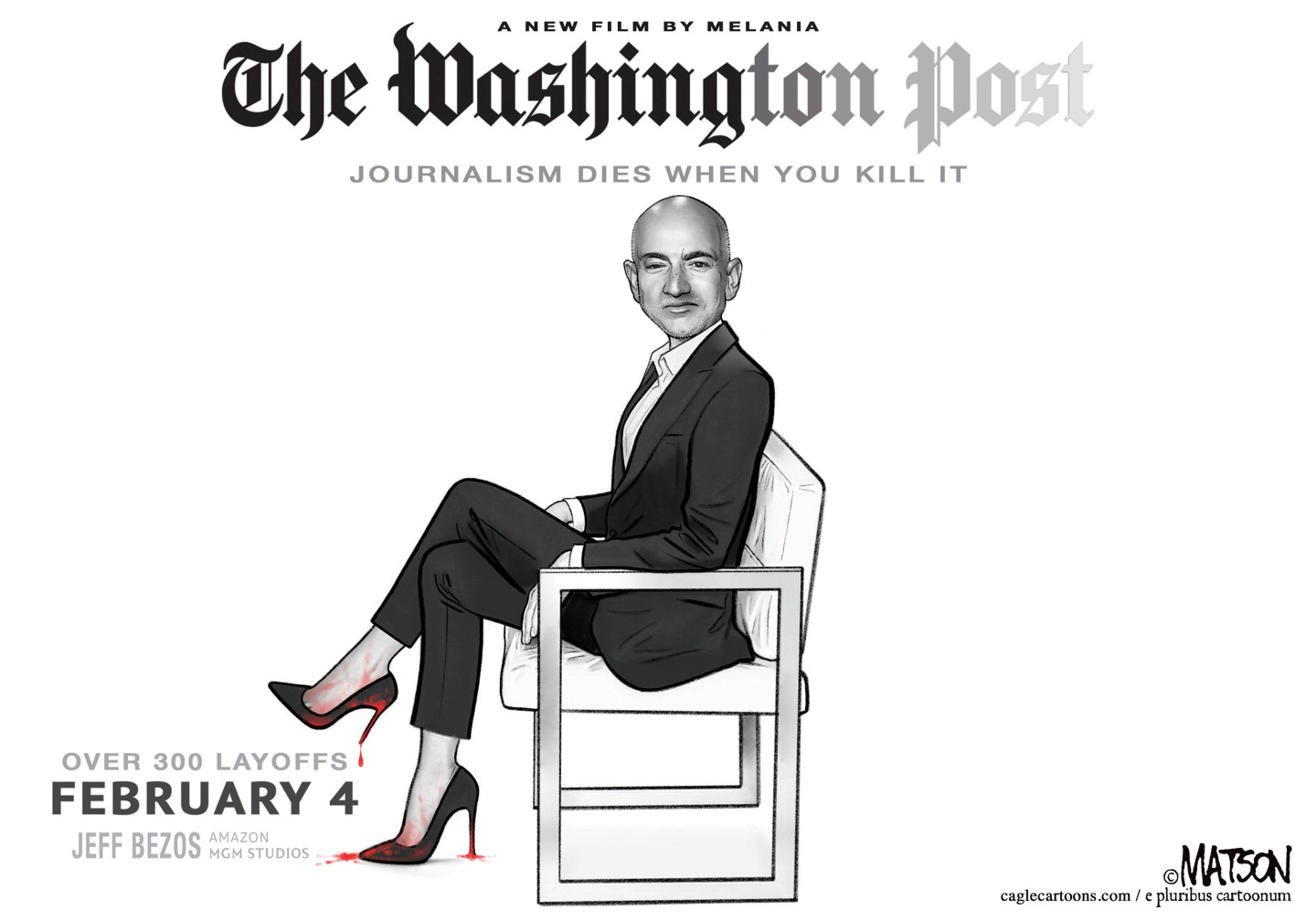

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred