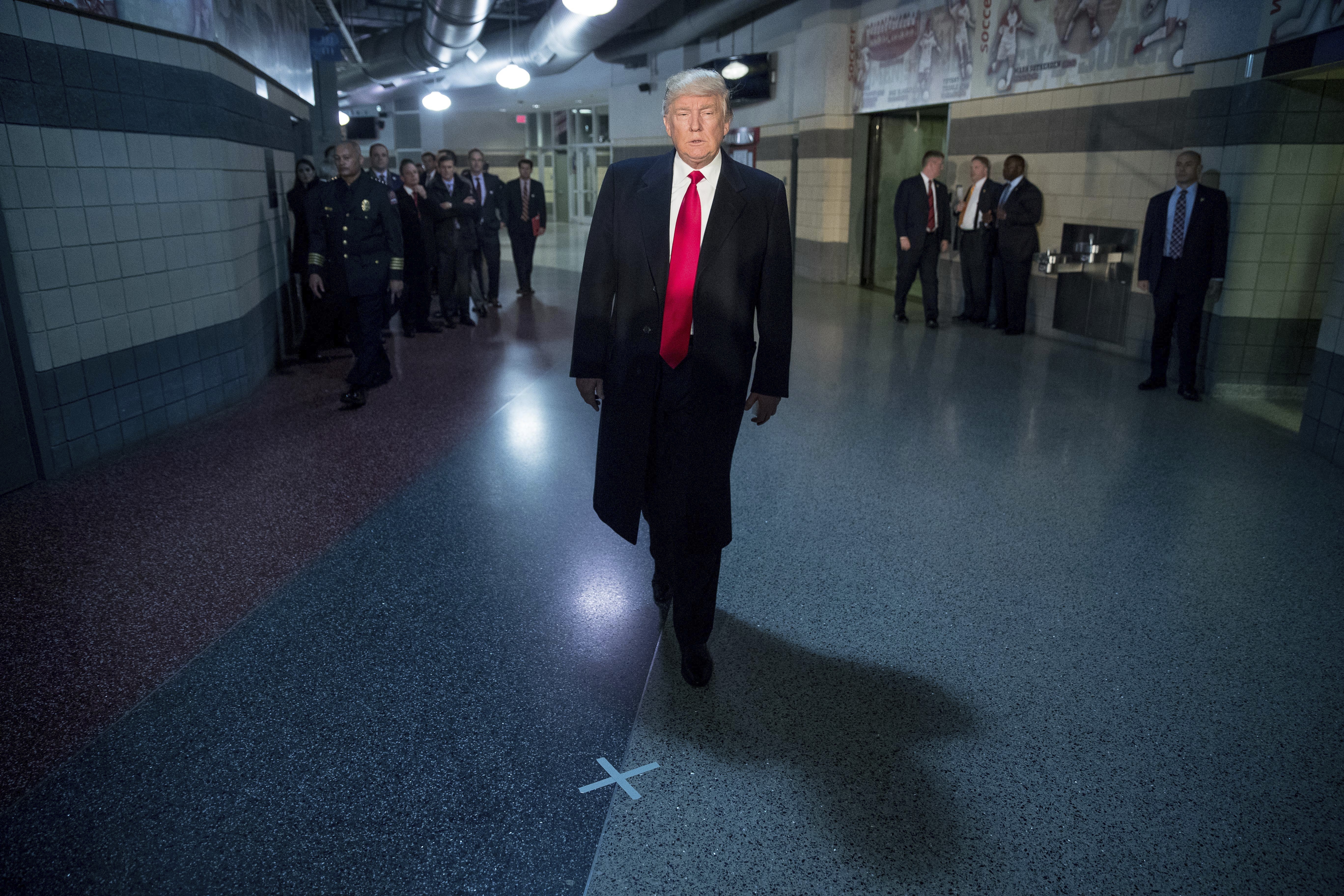

Donald Trump: The New Coke president?

Maybe voters want the real thing, after all

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1971, the Coca-Cola Corporation released one of the most iconic commercials of all time, featuring young people of all races and nationalities standing on a hillside singing about living together in harmony. Coca-Cola was on top of the world.

Then, 14 years later, in the middle of the cutthroat '80s, the beverage powerhouse nearly blew itself up with a brash, ill-fated decision in the U.S. market that threatened the entire global brand. Coke was losing market share to archrival Pepsi, and decided to go on the offensive with a brazen coup de grâce: a new formula, test-marketed and rolled out with great aplomb.

"New Coke" was a disaster, one of the biggest marketing flops in history, and 79 days after consigning the 99-year-old formula created by Dr. John Pemberton to the dustbin of history, the old Coke was resurrected in July 1985 as "Coca-Cola Classic"; "New Coke" was demoted to "Coke II" in 1992 and then ignobly killed off over the next decade.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The taste tests got it wrong. Americans, it turned out, liked things the way they were; they wanted "the real thing," and New Coke wasn't it.

Believe it or not, there's a lesson here for Donald Trump. If he's not careful, he might wind up the "New Coke" of presidents.

Trump's campaign slogan — "Make America Great Again" — might sound like the rallying cry of the groups that spouted up to demand Coke bring back its old formulas, like "the Society for the Preservation of the Real Thing" and "Old Cola Drinkers of America." It was pretty easy to Make Coke Great Again, though — just revert to the old formula. Making America Great Again is trickier; Trump wisely did not specify exactly what was "great" about the America he misses, or when it existed — a good bet would be the 1980s — but the slogan was successful. Millions of Americans liked the Dixie cups of Trump's new formula enough to give it a try.

But taste tests can be as deceiving as poll numbers, and Trump isn't heading into the White House with much popular support. The 40 percent of Americans who view him favorably, in inauguration week polling from Gallup and every major TV network, may be better than the 13 percent of soda drinkers who said they liked New Coke after its launch, but it's historically low for an incoming U.S. president. So far, the more voters get to see of the president-elect's presidential persona, the less they like it. "Among the last seven presidents-elect," notes Cathleen Decker at the Los Angeles Times, "he is the only one whose popularity dropped between election day and his swearing-in."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It isn't too late for Trump to turn this around, however. And the New Coke debacle offers some history lessons especially well-suited to a new president who, more than any of his predecessors, is the steward of a global brand.

1. Don't promise what you can't deliver

The first lesson comes from another classic 1980s phenomenon, a book called The Art of the Deal. “You can't con people, at least not for long," wrote Tony Schwartz, channeling Donald Trump, whose name adorns the book. "You can create excitement, you can do wonderful promotion and get all kinds of press, and you can throw in a little hyperbole. But if you don't deliver the goods, people will eventually catch on." Coke spent $4 million on market research and taste tests, and unknown millions more rolling out its new cola with great fanfare and aplomb. None of it mattered.

It may be too late to defuse the exorbitant promises Trump made during the campaign and transition. But he can and should start dialing it back.

2. You can't spoon-feed people something they don't want

"Thirty years ago, we introduced New Coke with no shortage of hype and fanfare," a Coca-Cola spokesman told CBS News in 2015. "And it did succeed in shaking up the market. But not in the way it was intended. When we look back, this was the pivotal moment when we learned that fiercely loyal consumers — not the company — own Coca-Cola and all of our brands." Trump's Mexico border wall is not popular, nor is his love-fest with Russian President Vladimir Putin, or his puerile tweeting. People have high expectations for him on creating jobs and boosting the economy. If he wants to become more popular, he should consider focusing on things Americans say they want.

On the other hand, you can change tastes if you stick with something long enough. The Democrats did a lousy job selling the Affordable Care Act to the American public, and they probably failed to build up enough of a popular firewall to keep ObamaCare alive in the Trump administration. Still, with the health law and its many popular provisions on the chopping block, ObamaCare is more popular now than it has ever been. It is entering Coca-Cola Classic territory, and now taking it away carries risks, too.

3. It's better to expand your fan club than shrink it

Coke's whole rationale for introducing New Coke was to gain market share, and when the opposite happened, the company reversed course. For Coke, the motive was profit, but presidents have more legislative capital when their approval ratings are higher — even if they don't believe the polls, members of Congress do. This seems pretty self-evident.

"The narrow focus of Trump's transition — appealing to those who already supported him while ignoring those who did not — has cost him," says Decker at the Los Angeles Times. "Where other presidents used the weeks before their inauguration to put the animosities of the campaign behind them and to try to knit the country together again," says Peter Baker at The New York Times, "Trump has approached the interregnum as if he were a television wrestling star," picking fights and showing that "he intends to lead more through force of personality than through the breadth of his coalition."

His ardent fans love Trump's style, but there aren't enough of them for that to be a winning strategy. Remember, some people preferred New Coke — and probably still wish it were for sale. "I had an uncle who loved New Coke," recalled conservative Trump critic Erick Erickson back in June. "The product certainly appealed to a particular sort. He was a routine liar who wound up in jail at one point. It takes all kinds and New Coke appealed to that kind. Trump too appeals to a particular kind of angry and aggrieved white guy who thinks everyone else agrees with him when really 70 percent of the nation does not."

4. If you make a mistake, apologize, change course, and move on

Coke took a short-term hit from its New Coke debacle, but it calls the endeavor a long-term success. "Obviously, this was a blunder and a disaster, and it will forever be," Robert Goizueta, Coke's chairman and CEO during the New Coke flap, said in 1995. But in the 10 years since that blunder, Coke's market capitalization grew to $75 billion from $9 billion because, Coke says, taking away the original Coke formula made people realize how much they treasured it. (Today, Coke has a market cap of $178 billion.)

New Coke's failure was not "a carefully planned marketing ploy," Goizueta said — "we are not that smart and we're not that dumb" — but "if we had it to do all over again, knowing what the results would be, we would do precisely the same thing." Whether it was on purpose, Coke acknowledged its mistake, cut its losses, and rebounded to new heights. Trump is famously loathe to apologize. "Whatever you do, don't apologize," he told radio host Howie Carr during the campaign. "You never hear me apologize, do you?"

5. There's nothing like the real thing, baby

Coke had been selling itself as "the real thing," immutable and timeless, since adman Bill Backer came up with the slogan in the 1960s, and so suddenly changing its "real" formula threw a wrench in its brand identity. Pepsi even threw in a jab during the New Coke launch, saying its rival tacitly admitted it was not the real thing after all. The buy-in for Coke's "real" essence was so strong that panicked customers ran out and filled their basements with the original Coca-Cola after the New Coke roll-out, including, Coca-Cola says, a man in San Antonio who dropped $1,000 on cases of Coke from a local bottler.

If Trump can convince people that he's Coca-Cola Classic — an old, white male, just like the first 43 presidents — he might be able to tap into that welcoming embrace of the familiar. So far, he's not conforming to what people expect from a president. The risk for Trump is that he'll be New Coke, sparking nostalgia for a president who doesn't punch back at every slight, doesn't act like running the country is less important that his business endeavors, doesn't gratuitously insult celebrities and threaten to jail politicians, and at least pretends to respect the role the news media plays in a free society.

If Trump can't or won't satisfy America's tastes, it's not clear who benefits — would Republicans voters once more embrace the political establishment of the party, Republican Classic versus Trump's New GOP? Would Democrats recoup their electoral losses in the 2018 midterms? But it's pretty clear who would lose — Trump. For a businessman whose fortune rests now on his brand, Trump allowing himself to become President New Coke might be the craziest thing in a mad, mad, mad world.

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred